Tombstone of Martha Senftleben at the cemetery between Michałowice and Piechowice / Photo by Marta Maćkowiak

Martha Binner was born in Niemcza (Nimtsch) on October 1st, 1859, as the daughter of Herman Oswald Binner, a master painter, and Ernestine Dorothy née Burgstadt, both Evangelicals. She married Bruno Senftleben, a technician from Świdnica (Schweidnitz). The couple settled in his hometown and had one son, Herbert, and one daughter, Margarethe. The years 1916 and 1917 proved tragic for Martha – first her husband passed away, followed shortly by her 22-year-old son, who died on August 8th, 1917, on the front in Bukovina. Interestingly, Herbert’s death was registered in Piechowice, where he was said to reside before his death, while according to the record, his mother still lived in Świdnica. I suspect he might have been staying with his sister, who married Alfred Georg Poludniok, a writer, in Piechowice in 1915.

Gravestones at the cemetery between Michałowice and Piechowice / Photo by Marta Maćkowiak

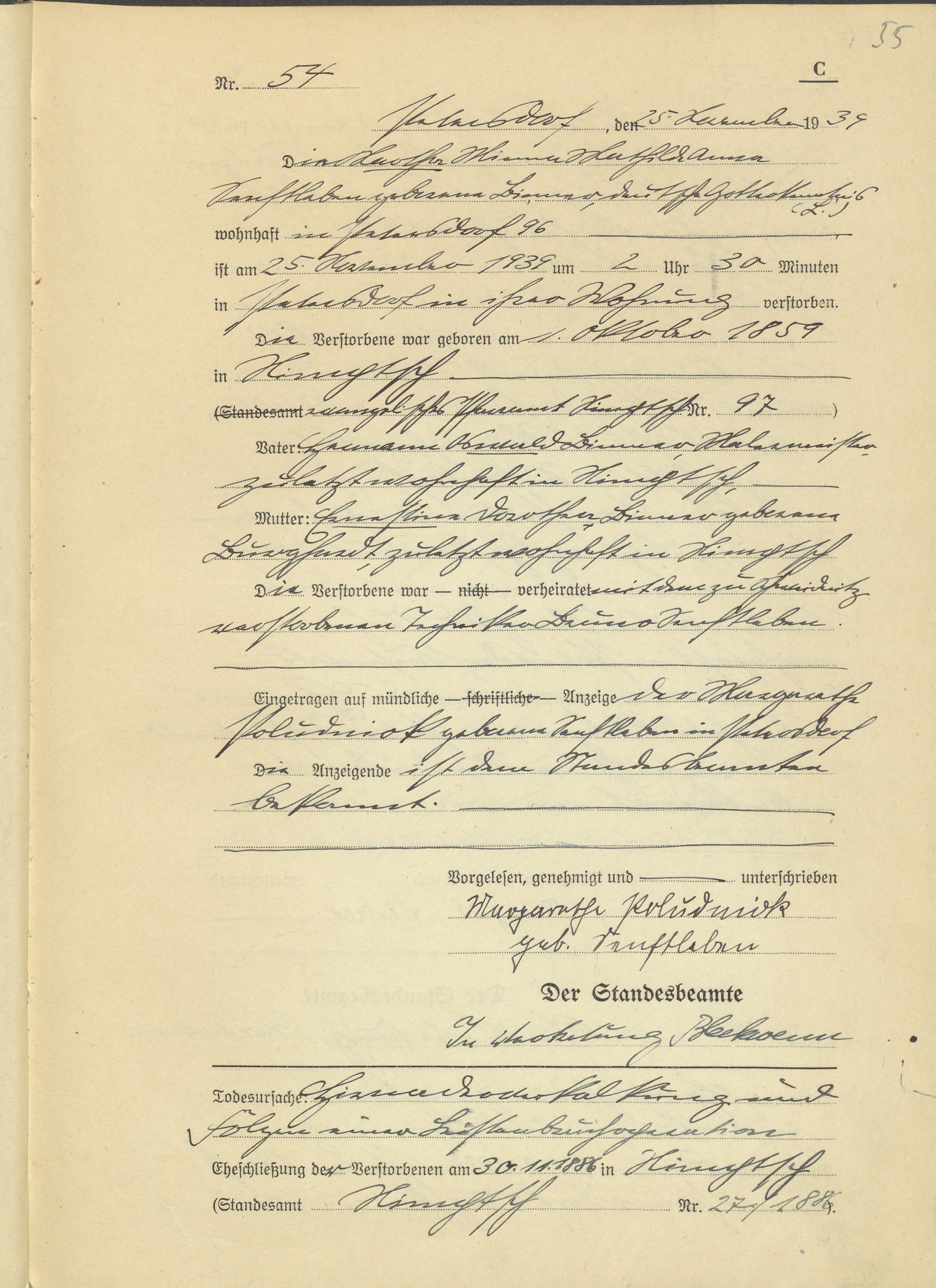

Going back to Martha – we know she passed away on December 25th, 1939. According to her death certificate, she passed away in her apartment in Piechowice (Petersdorf) 96, and her religion was listed as… Deutsche Gotterkenntnis, which literally translates to German Knowledge of God. And now the most intriguing part begins.

Death certificate of Martha Senftleben / Source: The State Archive in Wrocław, Jelenia Góra branch

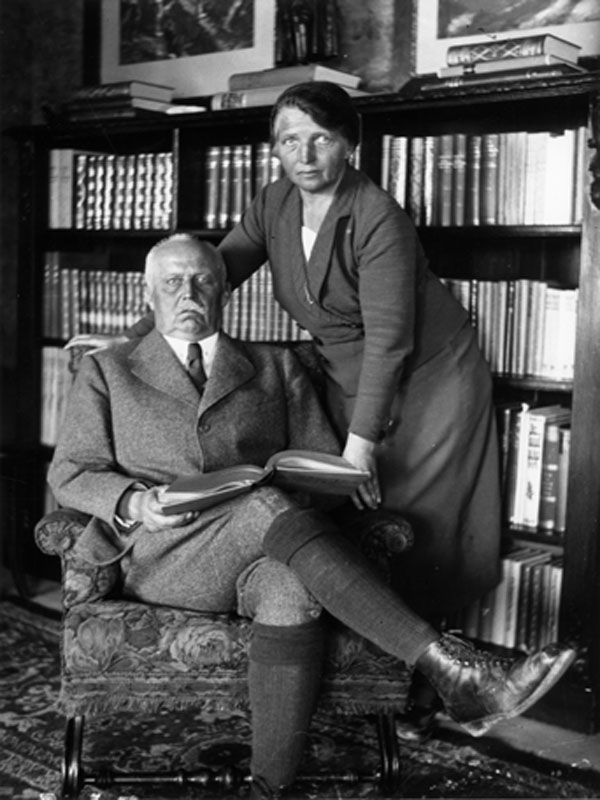

The religious movement Deutsche Gotterkenntnis was established by the controversial General Erich Ludendorff and his wife Mathilde von Kemnitz (Spiess). In the early 1920s, Erich was dubbed “the most dangerous man in Germany” and by others – the forefather of Nazism. He was the author of the controversial book “The Total War”, wherein he asserted that Germany’s fundamental objective was perpetual war and conquest.

In 1924, Erich established the Tannenbergbund association, which focused on political activities and “promoted a mystical pantheism with a Germanic-racist flavor.” In 1926, he married his second wife, Mathilde, a psychiatrist, who took charge of the religious aspect of Tannenbergbund – Deutschvolk, founded in 1930. Mathilde formulated its ideological principles, which were pantheistic, anthropocentric, and nationalist. The movement was extremely right-wing, anti-Semitic, and anti-Christian, to the point that even the NSDAP was considered too soft on this faith for them. Despite her involvement in the volkist movement, Mathilde opposed occultism and astrology, labeling them as a “Jewish distortion of astronomy,” and criticized theories suggesting the Indo-European origin of Germans. She aimed to create a new, genuine German religion.

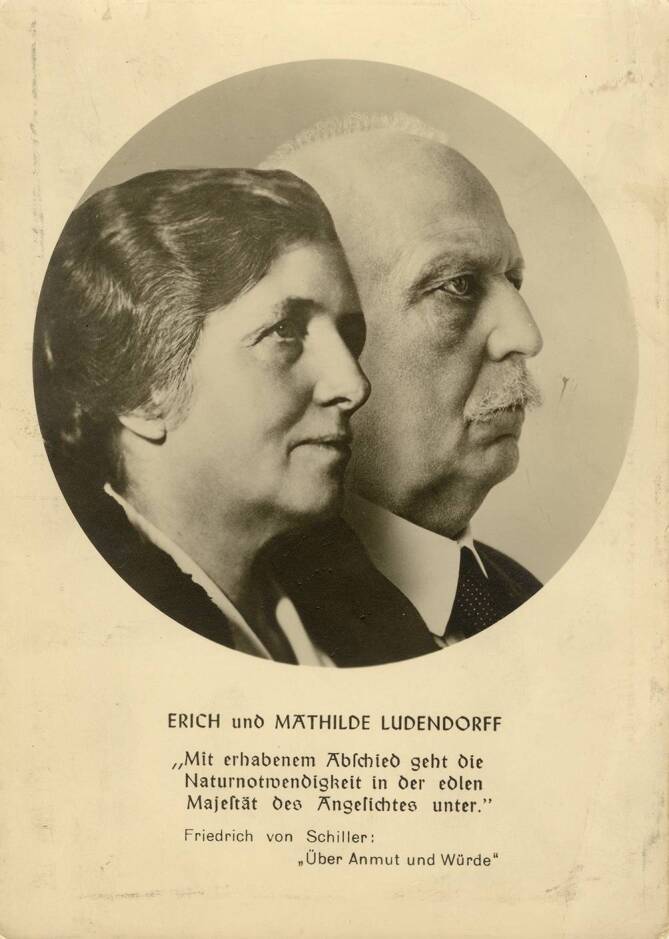

Erich and Mathilde Lundendorff

Because some of her views were extremely radical and bordering on conspiracy theories, the movement wasn’t universally regarded as credible. Mathilde Ludendorff asserted, among other things, that the Dalai Lama was guiding Jews in their supposed efforts to undermine Germany through Marxism, Catholicism, capitalism, and Freemasonry. She argued that Christian beliefs were incompatible with the Aryan ideal and that the Bible and Christianity themselves were fraudulent.

Despite this, in the early 1930s, the community boasted 320 local groups comprising approximately 15,000 members across the Reich. In 1933, the movement was outlawed by the authorities, but just 4 years later, in 1937, Erich gained approval to revive the religious movement, this time under the name Deutsche Gotterkenntnis, which continued the legacy of Deutschvolk. Consequently, German Knowledge of God became a state-sanctioned belief.

Erich passed away at the end of that same year. Meanwhile, in 1951, Mathilde established the Association for Gotterkenntnis, which had 12,000 members, and in 1955, she also founded a school. The association faced another ban from 1961 to 1977. It continues to operate today; as of 2010, it reportedly had around 240 members.

Erich and Mathilde Lundendorff

And circling back to the Karkonosze Mountains – new findings raise new questions. How did Martha become involved with Deutsche Gotterkenntnis? Could it be linked to her son-in-law’s artistic profession? Where did the community meetings take place? Did all those buried in Michałowice belong to the same movement, or perhaps different ones? Hopefully, we’ll uncover the answers soon!

Źródła:

In 1927, at 70 Hermsdorferstrasse in Bad Warmbrunn (now Cieplicka 70 in Cieplice Śląskie-Zdrój), lived Josef Galle, a senior tax secretary, Ernst Kuhlig, a chimney sweep, and Max Klein, a porter.

Contemporary view of the building / Photo by Marta Maćkowiak

The first page of Ernst Kuhlig’s marriage certificate / Source: Landesarchiv Berlin

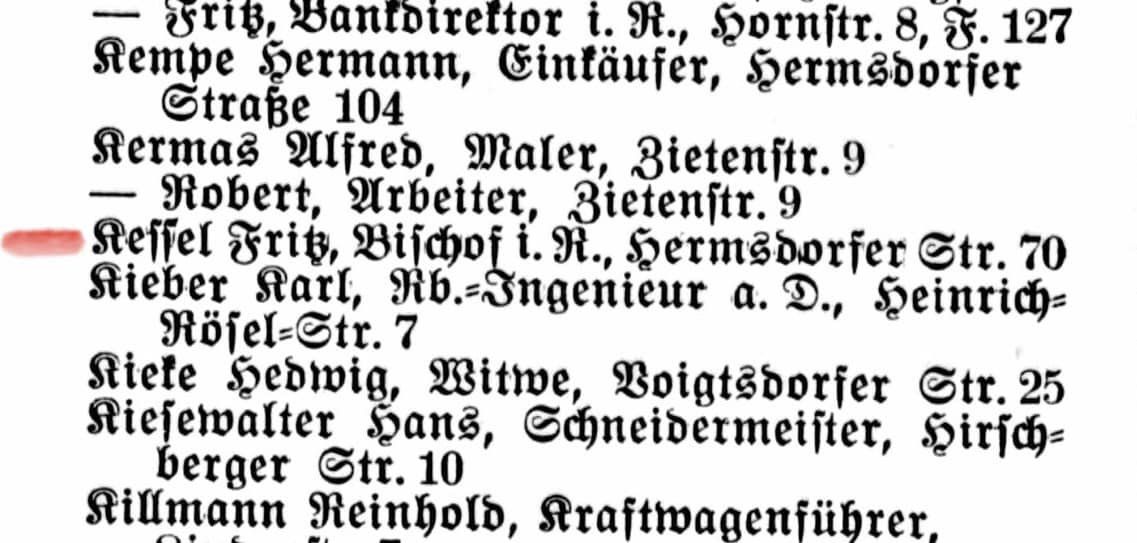

In 1939, Agnes Ludwig, a widow, resides in the villa alongside Bishop Fritz Kessel, who will be staying there at least until 1941. Upon further investigation, it seems likely that this refers to the controversial clergyman who, among other things, co-founded the pro-Nazi religious movement known as Deutsche Christen (German Christians). Fritz Kessel, born on March 10, 1887, pursued studies in Protestant theology at Königsberg (Królewiec), Heidelberg, and Breslau (Wrocław).

Address book from Bad Warmbrunn, 1941

After his studies, he participated in World War I. In 1917, he was ordained as a priest, and three years later, in 1920, he was sent to Brazil where he served as a pastor in Badenfurt (Santa Carolina). After another three years, he moved to Rio de Janeiro, and in 1925, he returned to Germany. He then became a parish priest in Parchwitz (Prochowice), and in 1928, he additionally took on a role in the parish of St. Nicolai in Berlin-Spandau. In 1932, he co-founded the aforementioned Deutsche Christen movement, and in 1933, he was appointed Bishop of East Prussia with headquarters in Königsberg – against the will of Gauleiter Erich Koch.

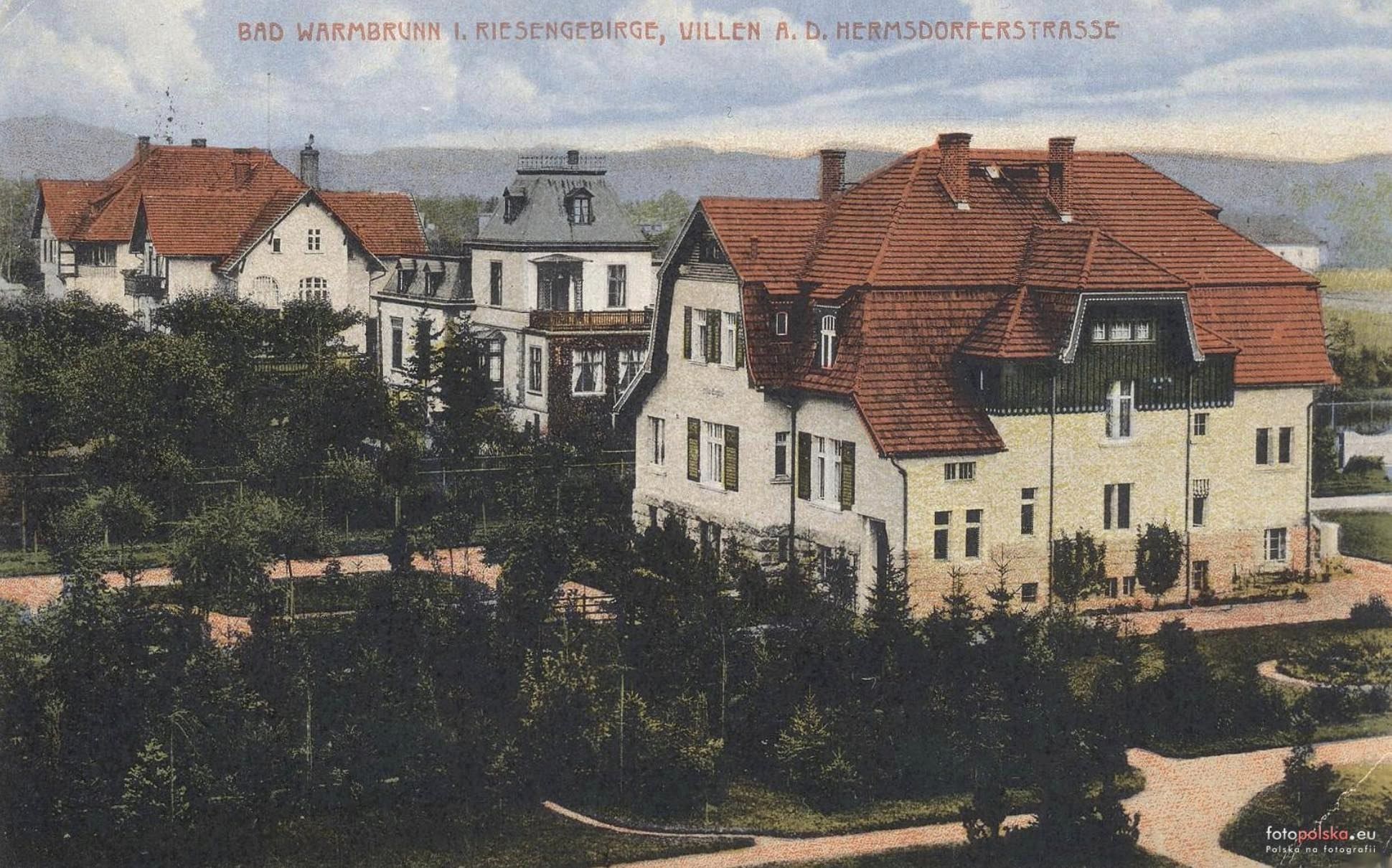

Archival photo of the building / Source: Fotopolska eu

Contemporary view of the building / Photo by Marta Maćkowiak

Sources:

Haus Wunsch currently / Photo by Marta Maćkowiak

Archival photos of the building / Source: Polska-org

I wonder what the signature dish was?

Contemporary view of the building / Photo by Marta Maćkowiak

Do any of you happen to know any stories about this building? Post-war tales are welcome too; feel free to share them in the comments!

Sources:

Villa Martha currently / Fot. Marta Maćkowiak

Archival photos of the building. On the left, a view from the garden side / Źródło: Polska-org

And that’s it. The trail has gone cold for now. At least I got some practice taking photos with the camera.

Contemporary view of the building / Fot. Marta Maćkowiak

Do any of you happen to know any stories about this building? Post-war tales are welcome too; feel free to share them in the comments!

Sources:

Interior of the building on Mornicka Street / Photo by Dudek Real Estate Agency

Historical view of the building / Source: Polska-org.pl

In that same building, there were residents like barber Meßner, Pastor Ratsch, and the Rosemann couple – Curt, a bank board member, and his wife Martha.

In 1939, Hermine Seidel still resided here along with legal trainee Werner Loecher, court inspector Georg Loechel, painter Paul Krause, pharmacist Odo Wanke, and, of course, Heinrich Drosdek, the owner of the pharmacy.

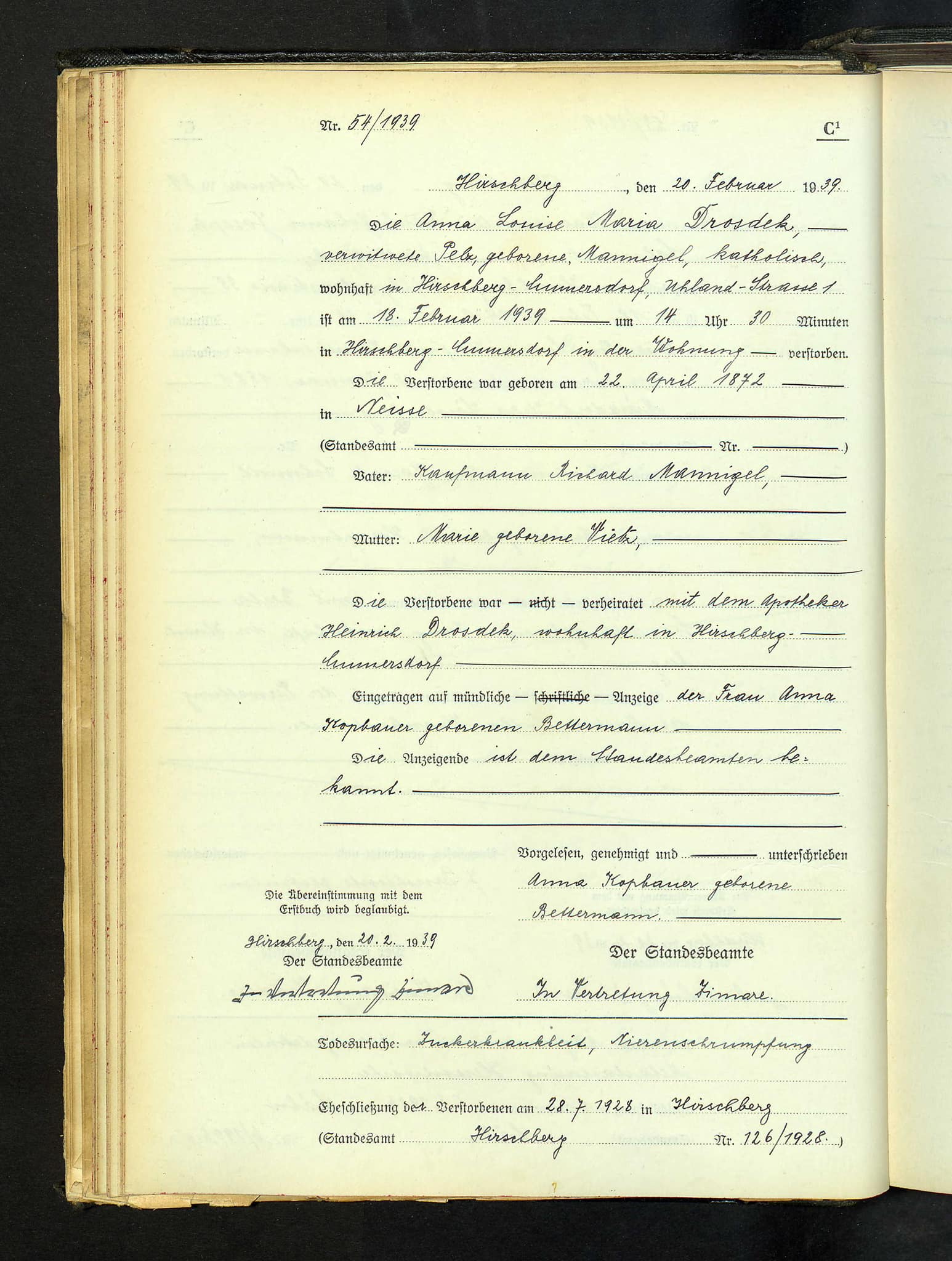

On July 28, 1928, 69-year-old Heinrich married 56-year-old widow Anna Luise Maria Pelz née Mannigel, originally from Nysa (Neisse). She was the daughter of merchant Richard Mannigel and Maria née Vietz. They shared 11 beautiful years together – unfortunately, on February 18, 1939, Anna Luise passed away due to diabetes and kidney failure.

Death certificate of Anna / Source: State Archives in Wrocław, Jelenia Góra branch

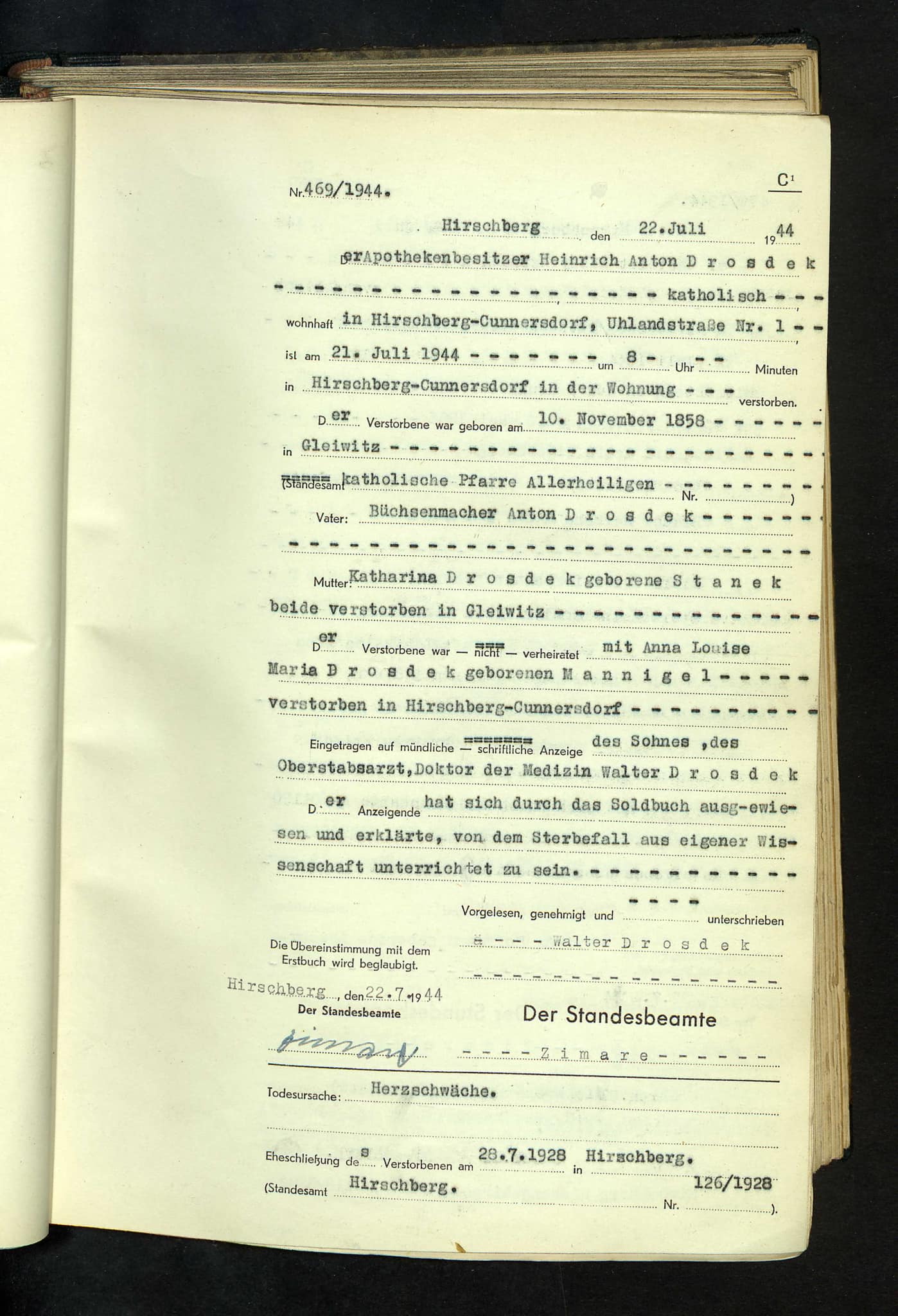

Heinrich lived here until his death. On July 22, 1944 his son, Dr. Walter Drosdek, a medical doctor, reported to the Civil Registry Office that his father, a Catholic and the son of the gunsmith Anton Drosdek and Katharina née Stanek, born on November 10, 1858, in Gliwice (Gleiwitz), had passed away on July 21, 1944, at 8 a.m., due to heart failure.

Death certificate of Heinrich / Source: State Archives in Wrocław, Jelenia Góra branch

Interior of the building on Mornicka Street / Photo by Dudek Real Estate Agency

Źródła:

Building on Źródlana Street in Cieplice today / Photo by Marta Maćkowiak

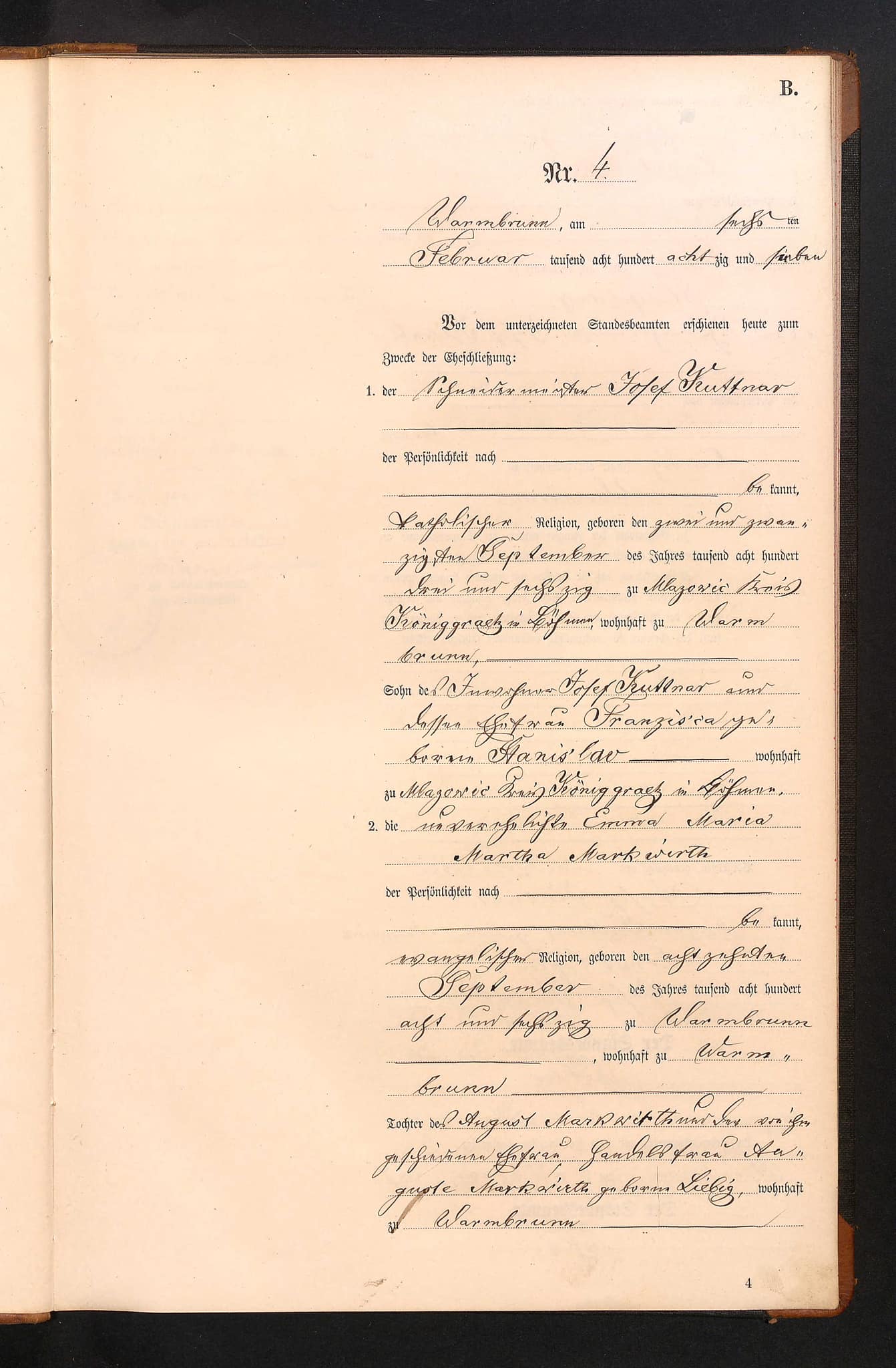

Marriage certificate of Josef and Marta / Source: State Archives in Wrocław, Jelenia Góra branch

According to the 1927 address book, Josef lived in a house near the river at Hospitalstrasse 9, just a 2-minute walk away (now Staromiejska 11A). In 1939, he moved back to his inn at number 5 – the street was now called Am Friedrischsbad. Also residing there were his son-in-law, Elfriede’s husband Otto Klötzke, a weaver by profession, widow Käthe Mustroff, police commander Paul Kath, senior prosecutor Lothar Jensch, and worker Martha Schäfer. Further details of their fate are currently unknown.

Details of the building that once hosted the inn / Photos by Marta Maćkowiak

Sources:

The building at ul. Wolności 246 in Cieplice / Photo by Marta Maćkowiak

I’ll gladly answer this question today. Before the war, the numbering was a bit different, and the address of the building was Warmbrunnerstrasse 105, Herischdorf (now part of Cieplice, post-war known as Malinniki). On the ground floor, there used to be Kronenapotheke, a pharmacy run by Konrad Tschanter.

Detail of the building at ul. Wolności 246/ Photo by Marta Maćkowiak

Konrad was born on March 1, 1859, in Głogów (Glogau), the son of Johann Karl Gottfried Tschanter and Marie Josephine Friederike Hoffmann, both of whom you can see in the pictures below.

On the right: Marie Josephine Friederike Hoffmann, on the left: Johann Karl Gottfried Tschanter, parents of Konrad Tschanter / Source: Rüdiger Tschanter, Ancestry

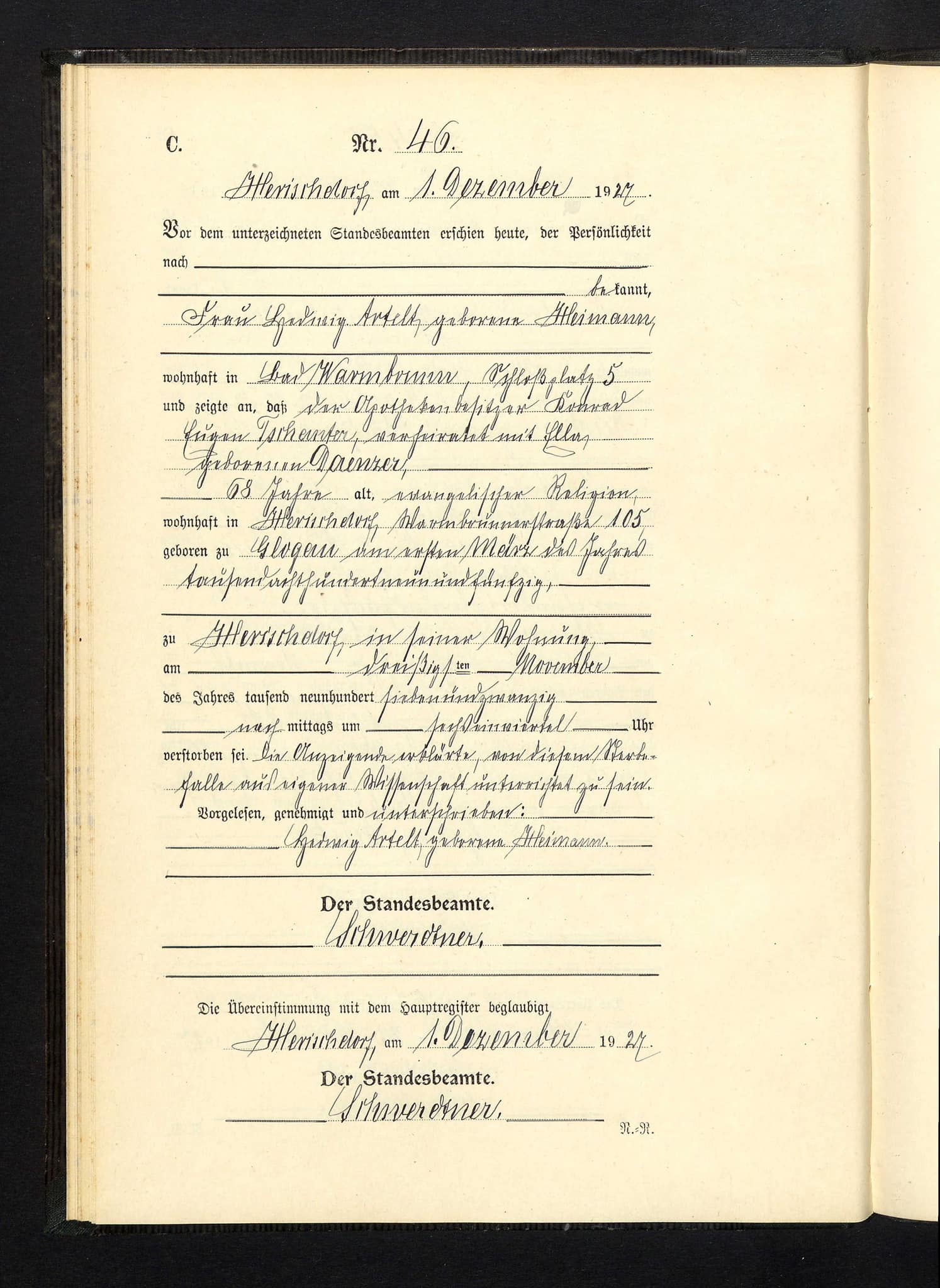

Death certificate of Konrad Tschanter / Source: State Archives in Wrocław, Jelenia Góra branch

Konrad’s wife, Ella Martha, remained in Cieplice, specifically in Malinnik, where she lived until March 1, 1945. Upon learning about the approaching Red Army, she reportedly took a fatal dose of poison.

Sources:

The gravestone of Minna Frieda Juppe / Photo: private archive of Ania, the owner of Domek pod Orzechem in Gierczyn.

On the right: Minna Frieda Juppe’s birth certificate, on the left: Minna Frieda Juppe’s death certificate / Source: State Archives in Wrocław, Jelenia Góra branch

Entry from the 1940 address book with the name Gustav Juppe

On the right: Gustav Juppe’s will, on the left: Gustav Juppe’s signature / Source: State Archives in Wrocław, Jelenia Góra branch.

Deed of sale / Source: State Archives in Wrocław, Jelenia Góra branch.

Archival photos of Domek pod Orzechem / Photo: private archive of Ania, the owner of Domek pod Orzechem in Gierczyn.

At least we know a bit more about the kind spirit residing in Domek pod Orzechem, lending a hand to the hosts. Discover it for yourself and consider Gierczyn for a weekend retreat.

Domek pod Orzechem today / Photo: private archive of Ania, the owner of Domek pod Orzechem in Gierczyn.

Thank you to Ania from Domek pod Orzechem for sharing the photos.

Sources:

Contemporary view of the villa formerly owned by Friedrich von Bernhardi / Photo by Marta Maćkowiak

Friedrich Adam Julius von Bernhardi

Friedrich’ s grandfather, Adam Johann Ritter von Krusenstern

Contemporary view of the house and photos of preserved historical interior details / Source: private archive

Friedric’s father-in-law, Wilhelm Günther von Colomb

Katharine also passed away first – on April 5, 1929, in her home at Warmbrunnerstrasse 104 (today ul. Tkacka 19), having lived for 75 years. Friedrich, at the age of 80, departed a year later – on July 10, leaving no descendants.

Death certificate of Katharine von Bernhardi (left) and Friedrich von Bernhardi (right) / Source: State Archives in Wrocław, Jelenia Góra branch

Thank you very much to the owners for sharing these beautiful interior photos.

Sources:

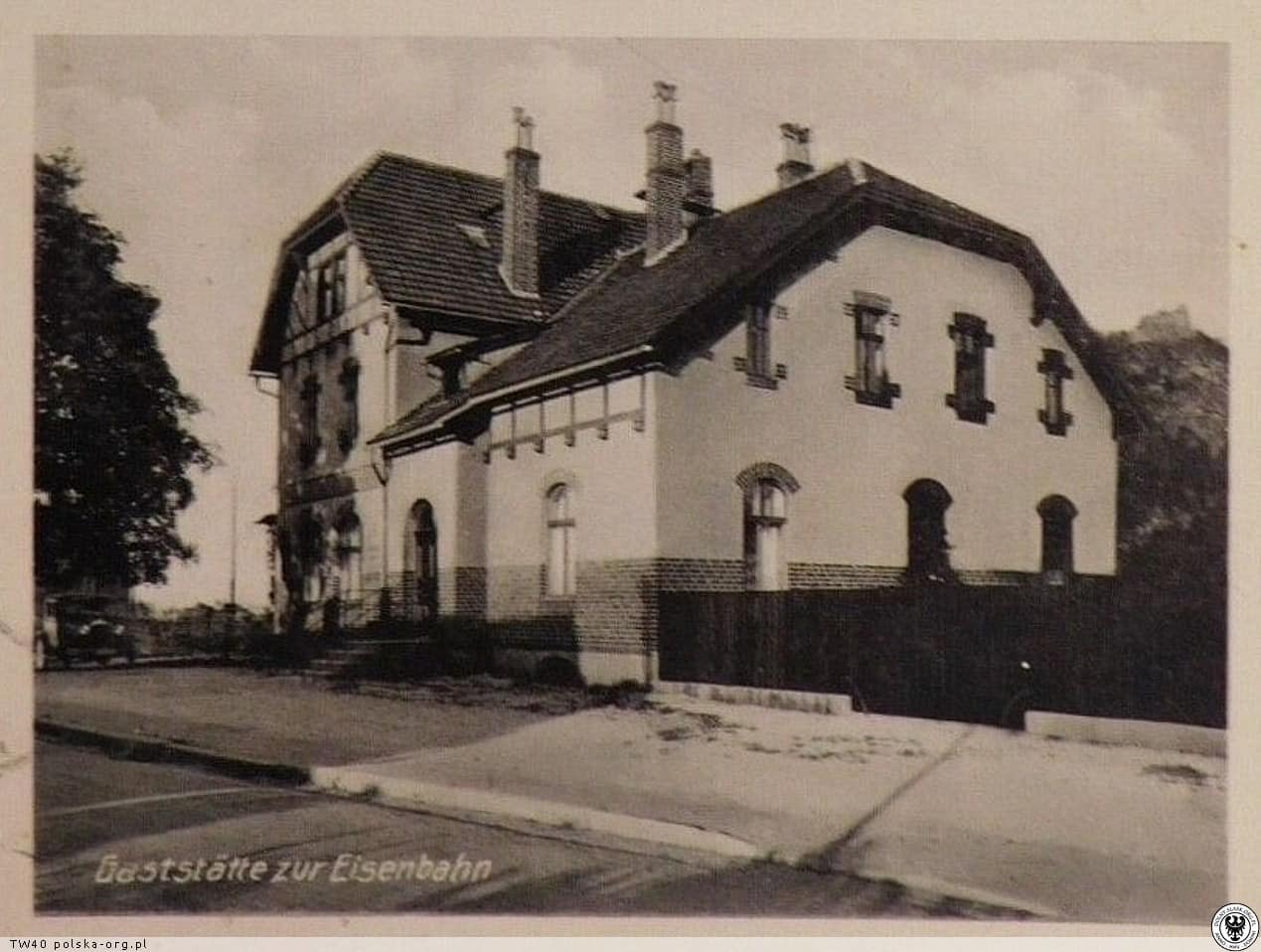

Zur Eisenbahn Inn, source: Polska-org.pl

On the left side, the first page of Elsa Werner’s marriage certificate; on the right – the first page of the marriage certificate of Elsa Werner and Emil Deckwerth.

From the marriage certificate, we can find out that Elsa was the daughter of Hermann Julius Werner, a restaurateur from Szklarska Poręba, and Anna Maria née John. The old Werner was the owner of Werner’s Gasthaus, an inn located at the site of today’s Museum of the Jizera Mountains (Muzeum Ziemi “Juna”, ul. Jeleniogórska 9, Szklarska Poręba; the building burned down in 2015 and was reconstructed). Interestingly, the original building was over 300 years old and stood on the foundations of an old watchtower. It housed the so-called Hunger Tavern, associated with the period of great famine. During public projects like building a mountain road along the Kamienna River, workers could receive, among other things, a loaf of freshly baked on-site bread.

Werner’s Inn, source: Polska-org.pl

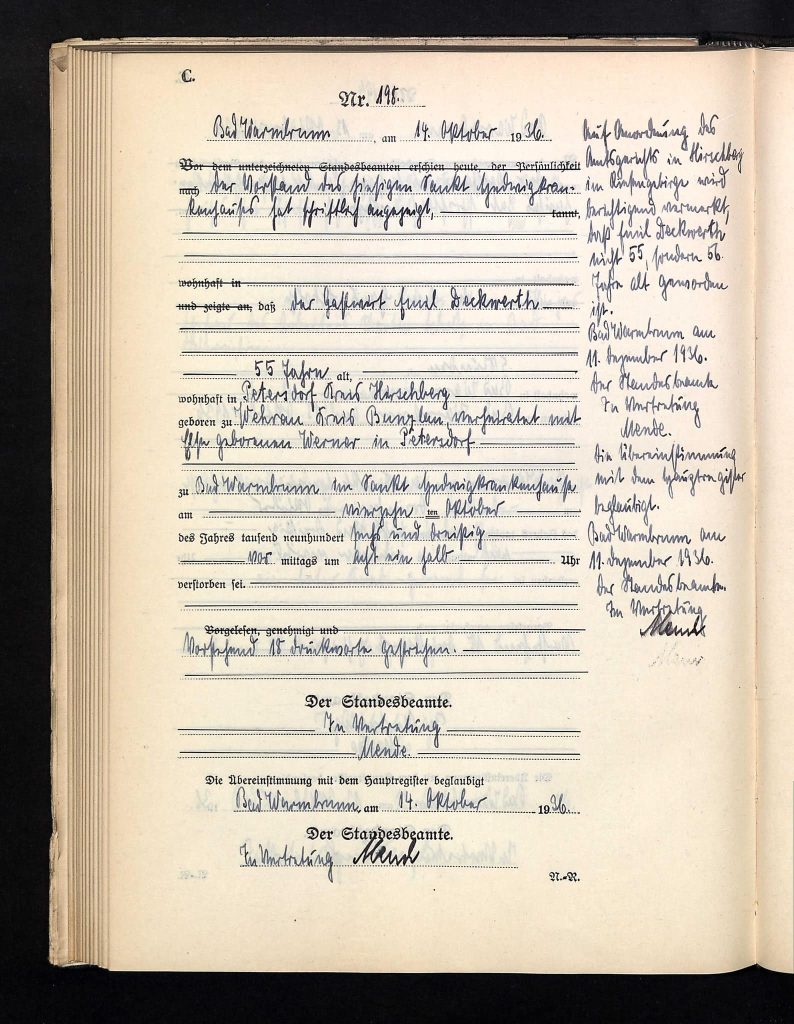

Emil Deckwerth’s death certificate

Returning to Piechowice and Elsa – her second husband, Emil Deckwerth, passed away on October 14, 1936, at the St. Hedwig Hospital in Cieplice Śląskie-Zdrój (Bad Warmbrunn) at the age of 55. Elsa continued to run the Zur Eisenbahn Inn until at least 1939, as documentation from the W. Schimmelpfeng Information Office from that year has been preserved. It is unknown whether they had children or if Elsa survived the war.

Zur Eisenbahn Inn, source: Polska-org.pl

Today, the building serves a residential purpose. Does anyone know if there was a restaurant in the building again after the war? Let me know!

Contemporary view of the building that once housed the Zur Eisenbahn Inn / Photo by Marta Maćkowiak

Sources:

Końcowy raport składa się z kopi odnalezionych dokumentów, tłumaczeń, zdjęć oraz podsumowania. Wyjaśniam pokrewieństwo odnalezionych osób, opisuję sprawdzone źródła i kontekst historyczny. Najczęściej poszukiwania dzielone są na parę etapów i opisuję możliwości kontynuacji.

Czasem konkretny dokument może zostać nie odnaleziony z różnych przyczyn – migracji do innych wiosek/miast w dalszych pokoleniach, ochrzczenia w innej parafii, lukach w księgach, zniszczeń dokumentów w pożarach lub w czasie wojen. Cena końcowa w takiej sytuacji nie ulega zmienia, ponieważ wysiłek włożony w poszukiwania jest taki sam bez względu na rezultat.

Raporty mogą się od siebie mniej lub bardziej różnić w zależności od miejsca, z którego rodzina pochodziła (np. dokumenty z zaboru pruskiego, austriackiego i rosyjskiego różnią się od siebie formą i treścią).

Na podstawie zebranych informacji (Twoich i moich) przygotuję plan i wycenę – jeśli ją zaakceptujesz, po otrzymaniu zaliczki rozpoczynam pracę i informuję o przewidywanym czasie ukończenia usługi. Standardowe poszukiwania trwają około 1 miesiąca, a o wszelkich zmianach będę informować Cię na bieżąco.

Na Twoje zapytanie odpiszę w ciągu 3 dni roboczych i jest to etap bezpłatny. Być może zadam parę dodatkowych pytań, dopytam o cele albo od razu przedstawię propozycję kolejnych kroków.

Warto pamiętać, że im więcej szczegółów podasz, tym więcej rzeczy mogę odkryć.

Podziel się ze mną:

I najważniejsze – jeśli masz niewiele informacji, zupełnie się tym nie martw, w takich sytuacjach także znajdę rozwiązanie.