In a couple of days most of us will sit at a table with family and friends. Festive time is good not only for feasting and playing board games, but also for reminiscencing those that are gone, watching family photographs and making surprise visits – it might be a perfect opportunity for collecting the information on our ancestors.

How to get down to it? Below, you will find the first steps from which it is good to start at the beginning of your genealogical adventure.

The engagement party of Jakub Mandelbaum and Mina Starobiniec, Warsaw / Source: private collection

At the beginning: set your goal. Ask yourself a question – who and what am I looking for? Motivations can vary – perhaps you wish to learn the names of your ancestors, discover the fates of an uncle who was never heard from again, or find the house in which your grandma spent her childhood. Perhaps there was a tale about a lost fortune, noble or Jewish origins, and you would like to get to know the truth, or perhaps you would like to learn anything as nobody ever wanted to go back to the things past?

Write everything down in a notebook – tick off the completed tasks and add new ones 😊

You probably know more than you think. Take a piece of paper and draw your family tree. Start with yourself, your siblings, parents, uncles, aunts, and so on, until you reach the point where all you can put down is a question mark.

Try to jot down all the details – names, surnames, dates of births, marriages, and deaths. Include additional relatives with whom the family is close, and on the side, write down all the family gossip, legends, secrets that were sometimes whispered about. War experiences, addresses, completed schools, and professions – every detail may later prove to be invaluable.

The next step includes family interview. Some interviewees will tell stories for hours, others will certainly be silent as a grave. Some may even get offended that we dig up what should long be forgotten. For some people, returning to the past may be a traumatic experience – in such a situation we should respect if we get a refusal, and we should give up and go back to the topic some other time. Sometimes what you need is time.

In an optimist scenario, you will find a person who wants to share the story of their life – take advantage of that! Make notes, record the speech, ask a lot of questions. The more detailed they are, the better. Try asking questions like: “What did your house look like? Who were your neighbours? How many brothers and sisters did you have? Did you have a dog or a cat?”, rather than saying generally “Tell me about your life”.

A good question is key to success. Even the language we use for communicating may play a vital role. I remember when a couple of years ago I had a meeting with an elderly man from abroad. His grandsons wanted to learn about their ancestors from Poland and they were waiting for him to begin sharing his story. I slowly started asking him about various things – all in vain. He did not remember anything, he knew nothing. He seemed to be very lost.

Only when I asked the same questions in Polish, the language he did not use since the end of the war, suddenly it triggered an avalanche of memories. It is good to similarly help your relatives remember by showing them family mementos and photographs, if you have such things.

Even if somebody from your family interviewed the oldest members, do it once again. It may happen that your grandma will tell you more or will reveal some unknown secret because you inspire the bigger trust, or she associated you with something.

Leon Kaziński in Nowe Miasto nad Wartą, July 6th, 1932 / Source: private collection

Look through documents in your family home, also ask the people you interview for them. Take photographs, scans, make notes and write everything down in one place on the computer, because later you may find yourself doing the same discovery for the fourth time (true story – it happened to me more than once in the case of my own family).

You may happen to find a birth certificate, a diploma, cuttings from a newspaper, letters, pieces of paper with seemingly “accidental” names and addresses. Collect and describe everything, and then store it in a specially prepared binder. Be a detective.

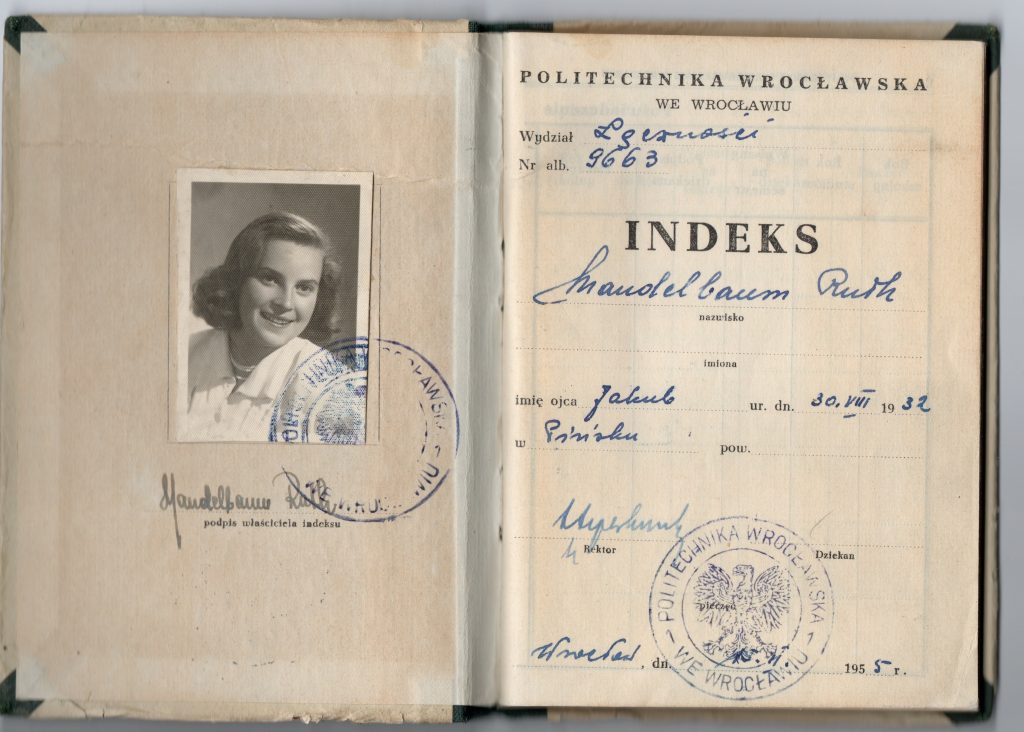

Ruta Mandelbaum’s student record book / Source: private collection

Use one of the most accessible information tools – Google search engine. That tip may seem silly or obvious, but I learned from my own experience that it is worth to pay some more attention to it.

By putting the searched phrase (in this case for instance the name and surname and the place of birth of an ancestor) in quotation marks – you can find incredible treasures. In this way I discovered the photograph of my great-great-grandparents on an archival Allegro auction. The subject of the auction was the letter Przewodnik Katolicki issued on June 5th, 1927 which contained the information about the golden wedding anniversary of Ignacy Maćkowiak and Ludwika Samela from Chocicza.

Ignacy and Ludwika Maćkowiak from Chocicza / Przewodnik Katolicki, June 5th, 1927

I hope that family meetings and stay at home will bear fruit in the form of multitude of new names, surnames and anecdotes. I am keeping my fingers crossed and I encourage you to share your new discoveries in comments.

It will be a great basis for further genealogical steps which I will describe in subsequent articles.

Marta

Impressum:

Design: lukaszhajduk.com

Code: tomhajduk.com

Photo: @kasia_kaleta

Polityka prywatności

Regulamin sklepu

All rights reserved ® Marta Maćkowiak 2025