On September 12th, 1926, Hedwig Krause, a 33-year-old resident of Bad Flinsberg (Świeradów-Zdrój), the wife of a butcher’s master, dies in a car accident on a bend leading from Seidorf (Sosnówka) to Baberhäuser (Borowice).

There are many articles about the stone commemorating the tragic event at Liczyrzepa Street. But there is nothing about Hedwig herself – who was she? Where was she from? It turns out that there is an interesting story behind the monument.

Photo by Marta Maćkowiak

Hedwig Krause from Bad Flinsberg (Świeradów-Zdrój – but was she, really? Hedwig was not born there. She also did not die on the day of the accident, on September 12th, as the inscription on the monument commemorating the event states. It is unknown what happened exactly, whether she was run down or there was a collision between two vehicles, or the driver lost control over the steering wheel – but it is certain that Hedwig did not die on the spot.

She was transported from the place of the accident to the hospital in Hirschberg (Jelenia Góra), where the death was confirmed the next day, September 13th, 1926, at 11:00 p.m.

Hedwig did not come from Bad Flinsberg or Seidorf, or from any other nearby town. She had lived in the vicinity of the Jizera Mountains for at least 6 years because on January 20th, 1920, she got married in Bad Flinsberg. Her husband was the butcher, Wilhelm Gustav Krause, 16 years older than Hedwig.

Hedwig Emilia Minna née Schulze was born on June 2nd, 1893, in a town 200 km away from Flinsberg – in Frankfurt on the Oder. She was the daughter of a butcher’s master, Richard Schultze and Minna née Frikel, who lived even further away, in Küstrin (Kostrzyn nad Odrą). Richard and Minna lived in the Old Town in the house at number 115. However, there is no trace of the house today apart from a few bricks and a piece of the foundation that have survived. But certainly nothing more because the Old Town of Kostrzyn, called by some the Pompeii on the Odra River, was razed to the ground in 1945.

The groom, rather older than younger, as he was 43 on his wedding day, was born on December 11th, 1877, in Bad Flinsberg. He lived in house number 149, probably on Hauptstrasse (today ul. 11 Listopada), according to the information from the address book dated as 1930, Gustav was the son of the glazier Erdmann Krause, who started renting guest rooms at the end of his life in his house in Schreiberhau (Szklarska Poręba), and Augusta née Männich.

A piece of address book from Bad Flinsberg, 1930

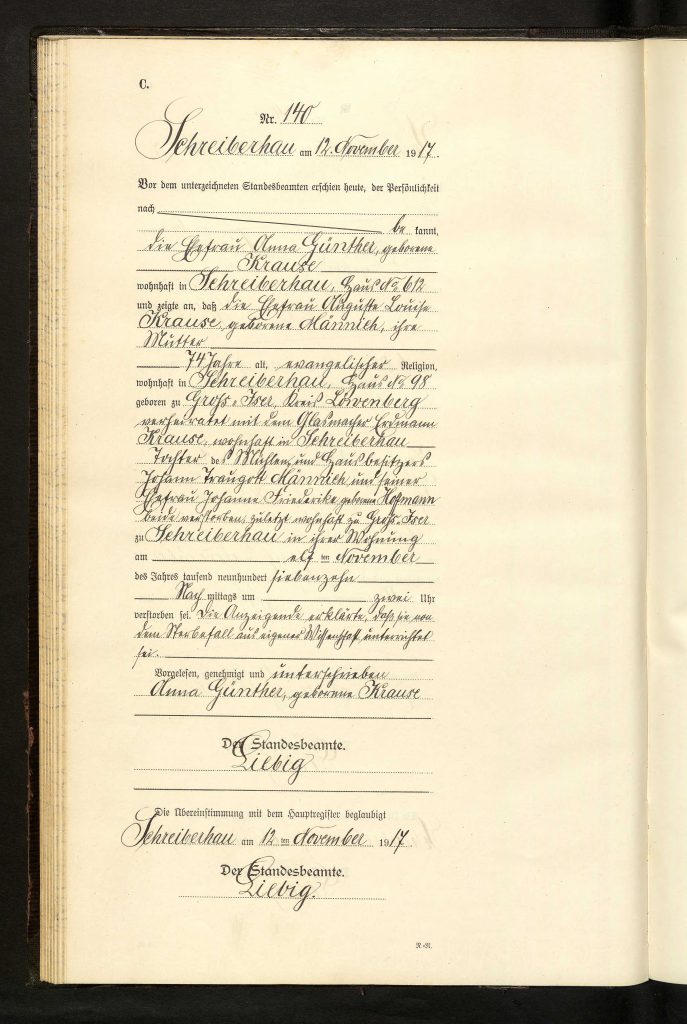

A death record of Hedwig Krause née Schulze

Wilhelm Gustav Krause had at least three siblings, two older brothers, Julius Erdmann and Gustav Oskar and a sister, Anna.

On November 12th, 1917, Anna Krause née Günter, reports to the Registry Office that her mother, Auguste Louise Krause née Männich died the day before at 11:00 a.m. in her house at number 98 in Schreiberhau. She also added that Auguste was 74 years old and was born in Gross Iser as the daughter of Johann Traugott Männich and Johanne Friederike née Hoffmann. The daughter of Johann, the owner of the mill and a house in Gross Iser. And as it turned out later – the founder of the now non-existent Isermühle shelter in the former settlement of Gross Iser.

In 1874, Auguste, Erdmann and their newborn son Julius stayed with their grandparents in this small village in the Jizera Meadow. Later, however, they will move first to Bad Flinsberg and finally to Schreiberhau.

Hostel Isermühle / Source: Polska-org.pl

The Isermuhle’s remains / Source: Ragnar, Polska-org.pl

On July 15th, 1921, Julius Erdmann Krause, a forester living at Erlenweg 828 (today’s Zdrojowa Street) in Szklarska Poręba Górna, reported the death of his 80-year-old father, also Erdmann. He rested next to his wife, Auguste, in the Evangelical cemetery in Szklarska Poręba.

Going back to Gustav and Hedwig – it is unknown whether they had any offspring within 6 years of living together. It is also not known what happened to Gustav after the tragic death of his wife.

However, I came across an interesting information – namely the remark about Wilhelm Gustav Krause from Bad Flinsberg, the father of three children, who died on November 29th, 1939, in Cieplice Zdrój, the husband of Dorothea Schulze, born on March 24th, 1907, in Küstrin.

The question is – is it a coincidence or Hedwig’s younger sister?

The Protestant cemetery in Schreiberhau (Szklarska Poręba) / Photo by Marta Maćkowiak

Sources:

The Hall of Legends, also known as the Hall of Fairy Tales or in German as the Sagenhalle, was a unique place created by Hermann Hendrich. Inspired by legends of the Spirit of the Mountains, mysticism, and Germanic mythology, it stood in Szklarska Poręba even after the war. Unfortunately, within a few years, it was completely destroyed. To prevent the Hall from falling into complete oblivion, I would like to dedicate today’s article to it and to Hermann.

Sagenhalle (Hall of Legends) in Szklarska Poręba / Source: polska.org.pl

Nestled in picturesque surroundings, Szklarska Poręba (formerly known as Schreiberhau) rose to prominence as a fashionable resort and leisure destination by the late 19th century. During this period, the Karkonosze Mountains were renowned for numerous legends and mysterious tales, including those of Rübezahl, the Spirit of the Mountains, Walons in search of treasures, and herbalist-alchemists. This attracted throngs of painters, writers, and representatives of the scientific community, who collectively formed a cultural phenomenon in Szklarska Poręba – an artists’ colony.

One of them was Hermann Hendrich, a German painter from the Harz Mountains, born on October 31st, 1854, in Heringen, Thuringia. His parents were August Hendrich and Auguste Friederike, née Ziegler. After an inspiring artistic journey to Norway in 1876 and a stay in the United States with his brother, he returned to Germany. From 1886 to 1889, he studied landscape painting under Joseph Wenglein in Munich and Eugen Bracht in Berlin. He was also a member of the Elf group and co-founder of the Berlin Secession.

On April 14th, 1898, he married Clara Becker in Berlin. According to the marriage certificate, Christian Hermann and Theresia Clara were residing at Friedrich Wilhelm Strasse 16 at the time. Both sets of parents had passed away by 1898. Hermann’s father, Friedrich August Hendrich, lived in Benungen, while his mother, Friederike Auguste (née Ziegler), resided in Greencastle, United States, likely with her second son.

Hermann’s wife, Theresia Clara Geene, née Becker, a widow of a butcher, was born on July 3rd, 1853, in Achen. She was the daughter of Didrich Becker from Hannover and Elizabeth Hartmann from Amsterdam.

Shortly thereafter, the young couple arrived in Szklarska Poręba.

Marriage certificate of Hermann Hendrich and Clara Becker / Source: State Archives in Wrocław, Jelenia Góra branch

Hermann was captivated by Germanic mythology, nature, and folklore. He also found inspiration in the works of Richard Wagner. Enthralled by the landscapes of Szklarska Poręba and the legends of Rübezahl, he decided to extend his stay here. Norwegian sacred architecture also greatly influenced Hendrich, and the presence of the Wang Church, transported from Norway in the mid-19th century to the nearby town of Karpacz (known as Krummhübel in German), served as a delightful reminder of his artistic journey from years past.

At Hermann’s initiative, the Hall of Legends, or Sagenhalle, was opened in the Valley of Seven Houses on May 30th, 1903. Its architecture drew inspiration from the local building style and ancient Germanic motifs, adorned with images of dragons, serpents, and runic symbols, among other decorations.

In the Hall, there was a series of eight massive paintings by Hendrich, illustrating the story of the Spirit of the Mountains: “The Garden of the Spirit of the Mountains,” “Goddess of Spring,” “Castle of the Spirit of the Mountains,” “Great Szyszak,” “Snowy Pits,” “Small Pond,” “Kamieńczyk Waterfall,” and “Mountain Ridge.”

Hermann Hendrich with his paintings in the Sagenhalle in Szklarska Poręba / Source: Polska-org.pl

On the exterior, the hall was crowned with two spears, between which hung the hammer Mjöllnir, belonging to the Germanic god of thunder, Thor, who represented home and family. Additionally, there was a symbolic oath ring called Eidring. The facade was adorned with shades of red, yellow, and blue. Adjacent to the entrance stood a large wooden statue of the Spirit of the Mountains, sculpted by Hugo Schuchardt and based on a painting by Moritz von Schwind. Known also as Rübezahl, Liczyrzepa, or simply Karkonosz – the Spirit of the Mountains personified the forces of nature and the ancient Germanic god Wotan for Hendrich.

The hall served not only as a gathering spot for artists and an exhibition venue but also became a tourist attraction. In 1927, extra railway connections were introduced from Jelenia Góra to Szklarska Poręba due to the growing interest from tourists. Additionally, every year, a massive bonfire was lit here on Midsummer’s Eve as part of the festivities of the folk-artistic festival Johanniswoche (St. John’s Week).

Sculpture of the Spirit of the Mountains sculpted by Hugo Schuchardt based on a painting by Moritz von Schwind / Source: Polska-org.pl

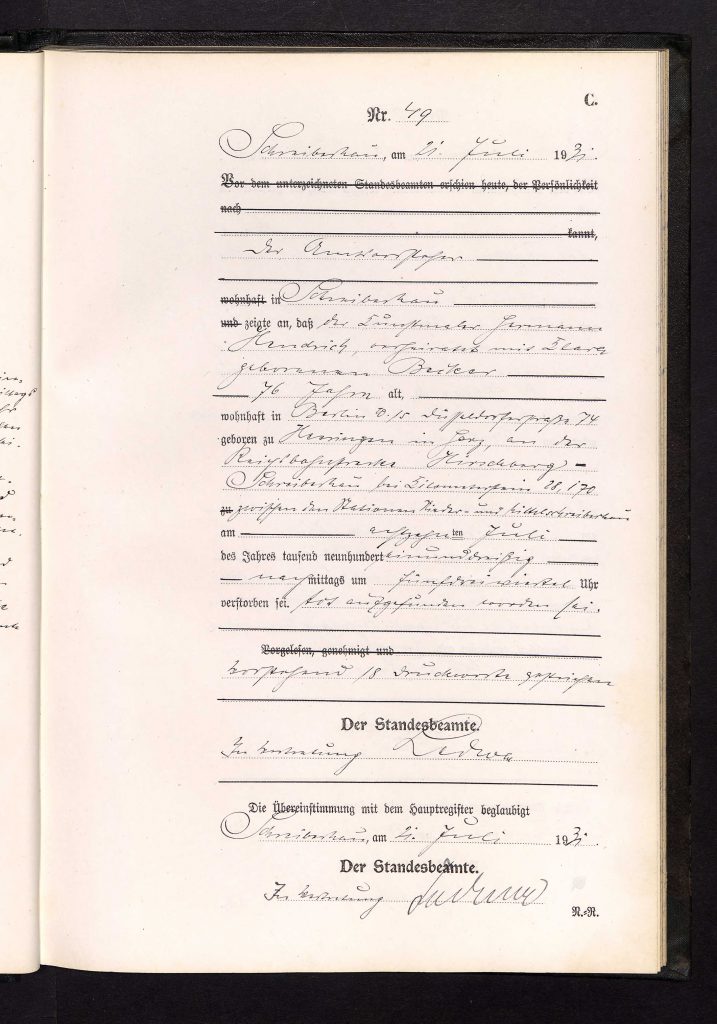

In 1927, Hermann Hendrich donated the Hall of Legends and his house (Hendrich Haus) to the municipality in exchange for a lifelong pension. The artist passed away in Szklarska Poręba four years later, on July 18th, 1931, at the age of 76, due to suicide. According to his death certificate, he resided in Berlin at Düsseldorfer Strasse 74.

Following Hendrich’s death, Wilhelm Bölsche resided here until his own passing in 1939. In the Hendrich Haus, he established a small geological and natural history museum, showcasing exhibits related to the Karkonosze and Jizera Mountains. As a tribute to this institution, the street where it is situated was named Muzealna (Museum Street).

Death certificate of Hermann Hendrich / Source: State Archives in Wrocław, Jelenia Góra branch

Despite surviving the war, the Hall of Legends faced disfavor from the new residents of Szklarska Poręba towards the Spirit of the Mountains and the artistic creations that originated here.

An article by Mr. Izbicki, which is particularly poignant, was published in Głos Ludu on May 21st, 1947:

“We must put an end to Rübezahl! We need to take a strong stance against the ‘sanctified’ cult of a certain Rübezahl, as glorified by the local courtier-graphomaniac, which translates literally into Polish as Liczyrzepa [Turnip-Counter].

With peculiar insistence, they turn this old man with a long beard trailing down to his ankles, wandering naked in the mountains, essentially a malicious, dim-witted creation of German literary fantasy – into a legend of some sort, akin to our Janosik or the Eastern Carpathian Dobosz.

On the covers of regional publications, postcards, advertising posters, shop signs, and, heaven forbid, “tourist souvenirs,” this old man with a monstrous club in his hand is supposed to symbolize a friendly and, to top it off, Slavic spirit of the Giant Mountains.

How in the world did anyone think this made sense, especially from a propaganda standpoint? Let someone just snatch that club away and keep pounding until they break apart this bizarre regional spectacle. In the museum in Middle Szklarska Poręba, they showcase these stories on several “landscapes.” The narrative backdrop aims to introduce visiting Poles to the essence of… typical German culture.

On the other hand, we think the best course of action is to burn these crude artworks, along with other paintings, decorations on the building, bas-reliefs, and anything else needed to prevent any culturally sensitive tourist from seeing them ever again.”

After some time, the paintings vanished, and the Hall started to decay. Today, in its spot stands the “Radość” [“Joy”] training and leisure center, owned by Wrocław University of Science and Technology. Luckily, Hermann’s house has been preserved, maintaining a style described by Małgorzata Najwer as “Nordic-Giant Mountain-Secessionist.” Reportedly, the entire area has been purchased by a new investor; let’s hope that Hendrich Haus will remain safe and the memory of its creator won’t be forgotten.

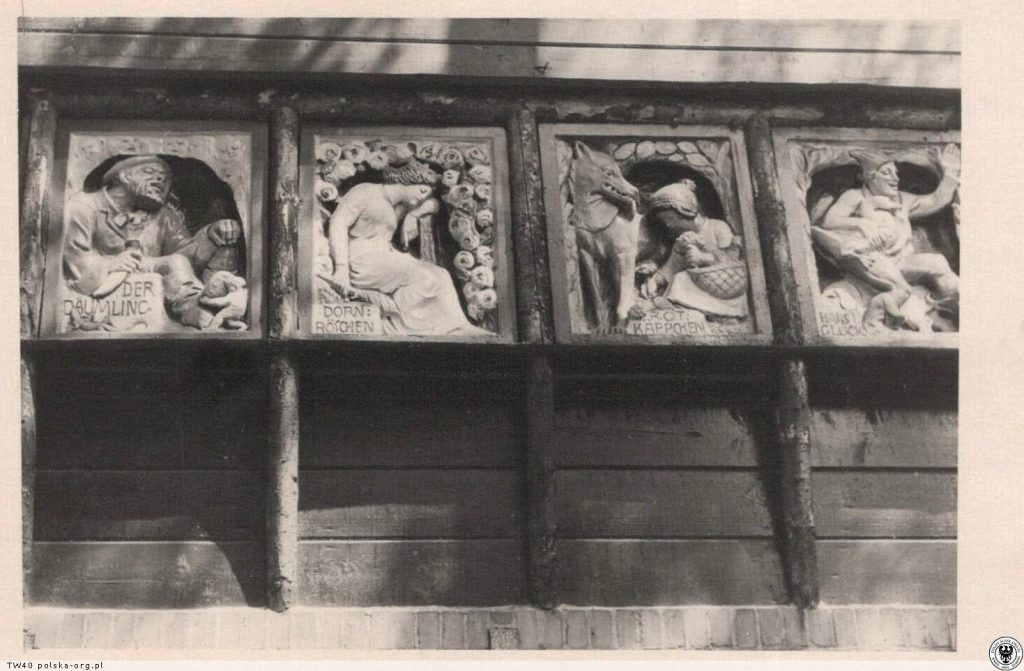

An interesting fact is that preserved sculptural elements from the Sagenhalle can be found on the facade of Primary School No. 1 in Szklarska Poręba.

Sculptural elements from the Hall of Legends / Source: Polska-org.pl

The Hall of Legends wasn’t the only building of its kind created by Hermann Hendrich. Another hall, the Walpurgishalle, actually the first one, was built in 1901 on the Hexentanzplatz (“Witches’ Dance Floor”) in the Harz Mountains. The third, Nibelungenhalle, near Königswinter, still stands and is open to visitors.

Marta

I visited the Protestant cemetery in Schreiberhau (Szklarska Poręba) for the first time a few years ago, and despite serious damages, I felt its uniqueness right away. Beautifully situated on a hill, quiet and forgotten.

Old Protestant cemetery at Waryńskiego 3 in Szklarska Poręba (Schreiberhau) / Photo by Marta Maćkowiak

I remember that it was difficult to walk through the overgrown alleys, the tombstones were unreadable, and the larger crypts were damaged and unsecured (I even saw a tibia in one of them). What a pleasant surprise was to learn about the social initiative Mogiłę Ocal od Zawalenia (Save the Tomb from Collapse). A group of German volunteers and the inhabitants of Szklarska Poręba organised themselves and decided to clean the cemetery and take care of the headstones. On October 23, 2021 at 4:00 p.m., I had a chance to attend the ceremony of replacing the tombstone of Carl Hauptmann, writer, playwright, philosopher and older brother of the Nobel Prize winner, Gerhart Hauptmann. Carl was an author of, among other things, The Book of the Mountain Spirit (Rübezahl), a significant character in this region.

Carl’s original tombstone, designed by his friends Hans and Marlene Poelzig, was unveiled on June 23, 1925. The following quote from a Silesian song was written on it:

“I rest here under a rose and a clover,

I will never be lost under them.

And every tear of mourning

which will drip from your eye,

will fill my grave with memory.

Every time when you are happy,

My grave is full of fragrant roses. “

Sadly the tombstone was destroyed, then reconstructed and now it is safe in the museum – the Hauptmann House in Szklarska Poręba.

On the left – unveiling the new tombstone of Carl Hauptmann / Photo by Marta Maćkowiak

On the right – Carl’s original tombstone / Source: The Hauptmann House

The necropolis was established in 1844 as a separate Protestant cemetery, but eventually people of other religions began to be buried here as well. The last burials took place around 1946 and since then it is abandoned. The cemetery is unique not only because of its location and mysterious aura – we can find here the graves of many painters, writers and outstanding people associated with the world of science in the 19th and 20th centuries. Before World War II, the Giant Mountains (German: Riesengebirge, Polish: Karkonosze) attracted crowds of artists who created an artistic colony in Szklarska Poręba which was a social phenomenon.

For example, the tombstones of Wilhelm Bölsche, his wife Joanna née Walther and their daughter, also called Johanna, have been preserved here.

William was a man of many talents – he was a writer, biologist, and literary critic. In the 1930s, he created a small, no longer existing, geological and natural museum at 5 Muzealna Street (ul. Muzealna 5).

The headstones of Wilhelm Bölsche, his wife Johanna Bolsche Walther and their daughter, Johanna / Photo by Marta Maćkowiak

In the central part of cemetery, there are romantic ruins of the Preussler family chapel, the first owners of the glass factory in Schreiberhau (Szklarska Poręba).

Photo by Marta Maćkowiak

I also noticed several tombstones with bees on them. According to the cemetery symbols dictionary this motif was quite rare and was associated with dilligence, virginity and innocence. A bee was considered to be a sacred being.

Photos by Marta Maćkowiak

I am so glad to see such a change. It seems that the cemetery will be no longer forgotten. I have heard that the historical walks will be organized soon and participants will have an opportunity to learn about the outstanding people who rest there and to restore the memory of all the pre-war inhabitants of Schreiberhau.

Photos by Marta Maćkowiak

Sources:

Impressum:

Design: lukaszhajduk.com

Code: tomhajduk.com

Photo: @kasia_kaleta

Polityka prywatności

Regulamin sklepu

All rights reserved ® Marta Maćkowiak 2025