When visiting the state archives in search of specific documents, I like to order ‘random’ folders to see if similar records might come in handy in the future. It’s like a lottery – sometimes I browse through hundreds of boring listings and calculations, and at other times, I discover incredible stories. One of those incredible stories is undoubtedly the story of Anna Drescher.

Villa Birkenhain in Krummhübel (presently Brzozowy Sad in Karpacz), ulica Sadowa 2 / źródło: Polska-org.pl

This time, I took on a folder concerning Judenvermögensabgabe, which can be translated as the Jewish Property Tax. Judenvermögensabgabe was a tax introduced on November 12, 1938, and it applied to every German Jew whose property was valued at a minimum of 5,000 marks. This tax was also referred to as the ‘penance tax’ because, after the assassination of the German Embassy Secretary Ernst Eduard vom Rath on November 7, 1938, by Herschel Grynszpan, a Polish-German Jew, Hermann Göring demanded the payment of one billion German marks as ‘penance’ for the damage caused to the German nation by Jews.

While reviewing case after case, my attention was drawn to Anna Drescher, who, in 1938, was residing in Villa Birkenhein in Krummhübel – today’s Brzozowy Gaj guesthouse located in Karpacz at ul. Sadowa 2.

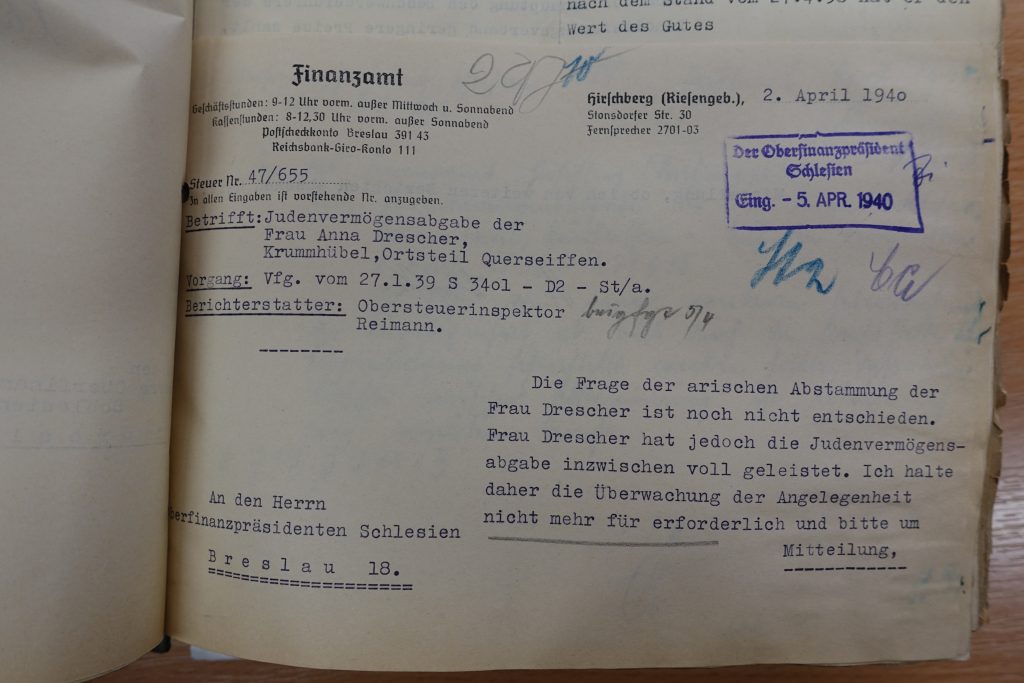

The first page of the folder: “The question of Mrs. Drescher’s Aryan origin has not yet been resolved” – so let’s see what this is about.

Page regarding Judenvermögensabgabe and Anna Drescher / Source: State Archive in Wrocław

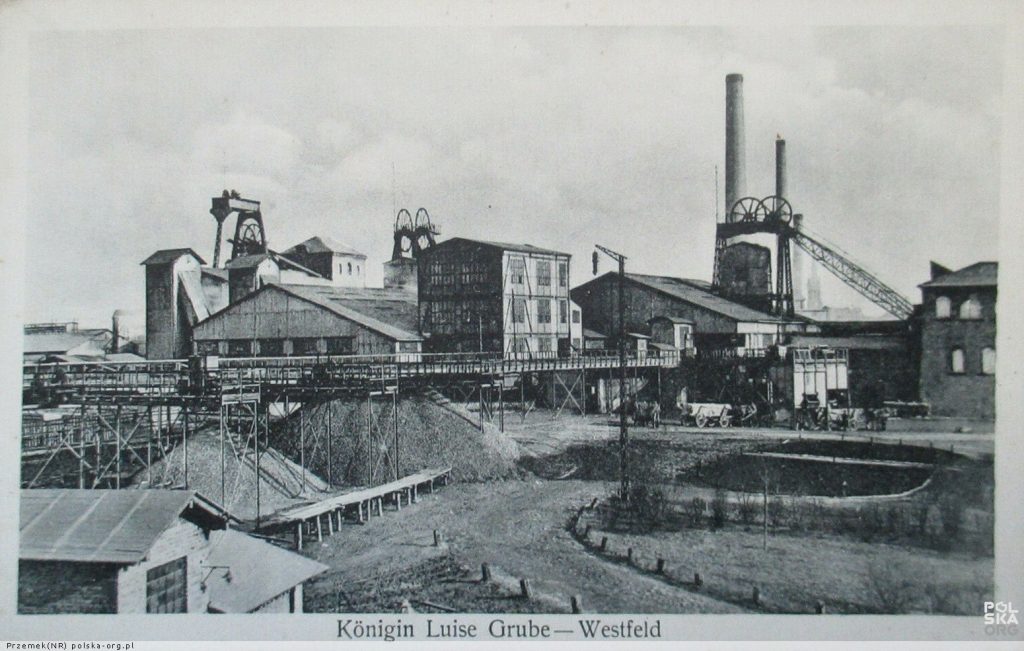

Queen Luiza Mine in Zabrze, 1920s-1930s / Source: Polska-org.pl

Fragment of the birth certificate of Franz Drescher and Anna Toeplitz’s daughter, along with information about their religion / Source: Landesarchiv Berlin

So, Anna Toeplitz was born in Wrocław (Breslau) on April 14, 1879, and was the second of nine children of Dr. Theodor Max and Franziska Toeplitz.

Photographs of Franziska and Theodor Max Toeplitz / Source: Ancestry, Stefan Toeplitz

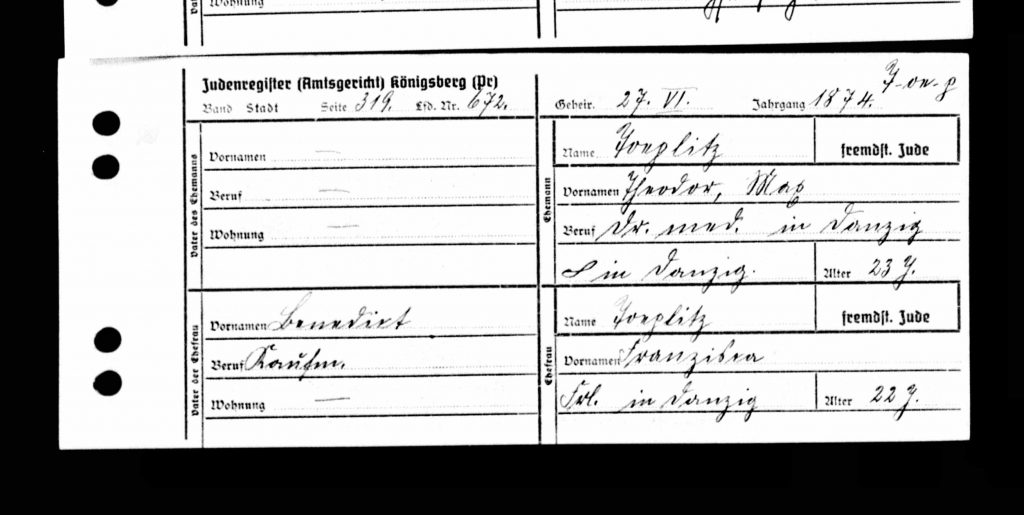

Marriage certificate of Theodor Max and Francizka Toeplitz, Kaliningrad (Königsberg) / Source: Records of the Evangelical Church in Königsberg

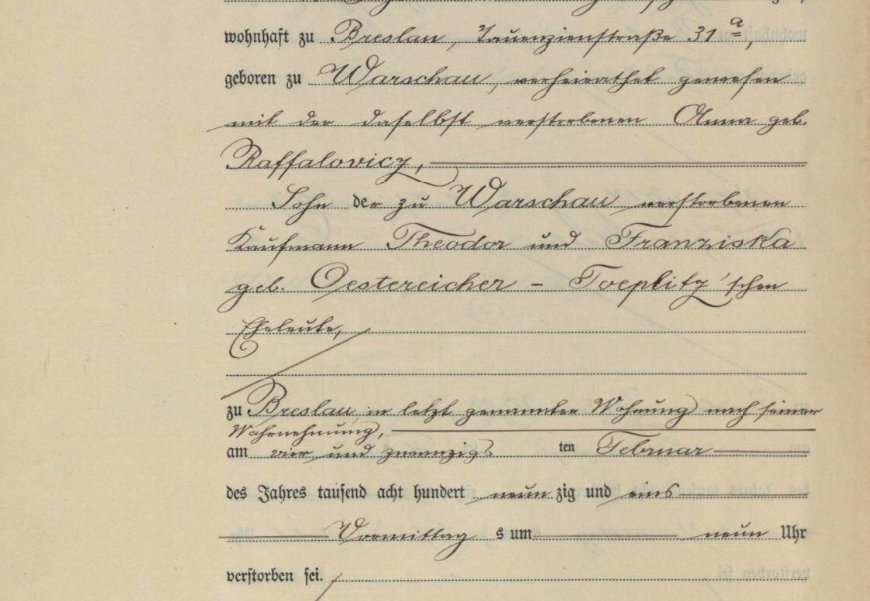

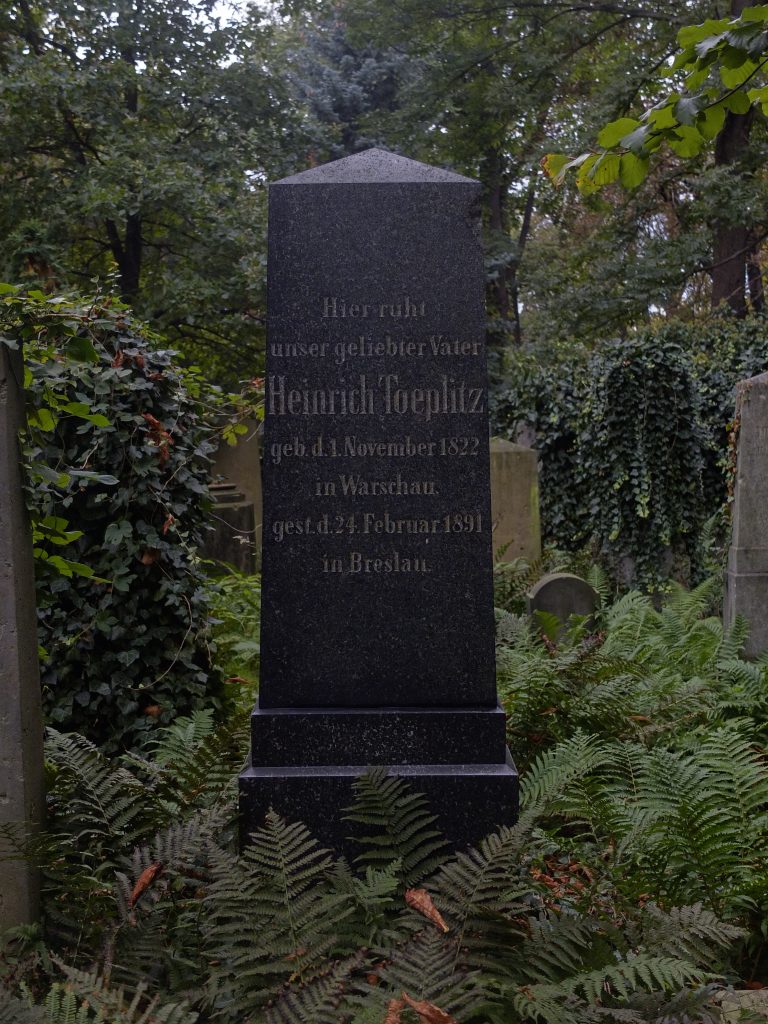

Excerpt from Heinrich Toeplitz’s death certificate / Source: State Archives in Wrocław

Tombstone of Heinrich Toeplitz at the Old Jewish Cemetery in Wrocław / Photo by Marta Maćkowiak

Returning to our heroine – Anna’s husband, Franz Drescher, passed away in Wrocław on January 20, 1934. Two years later, on October 12, 1936, Anna reported her mother’s death. She was living at Nova Strasse 4 (today’s Ksawery Liske Street) at that time.

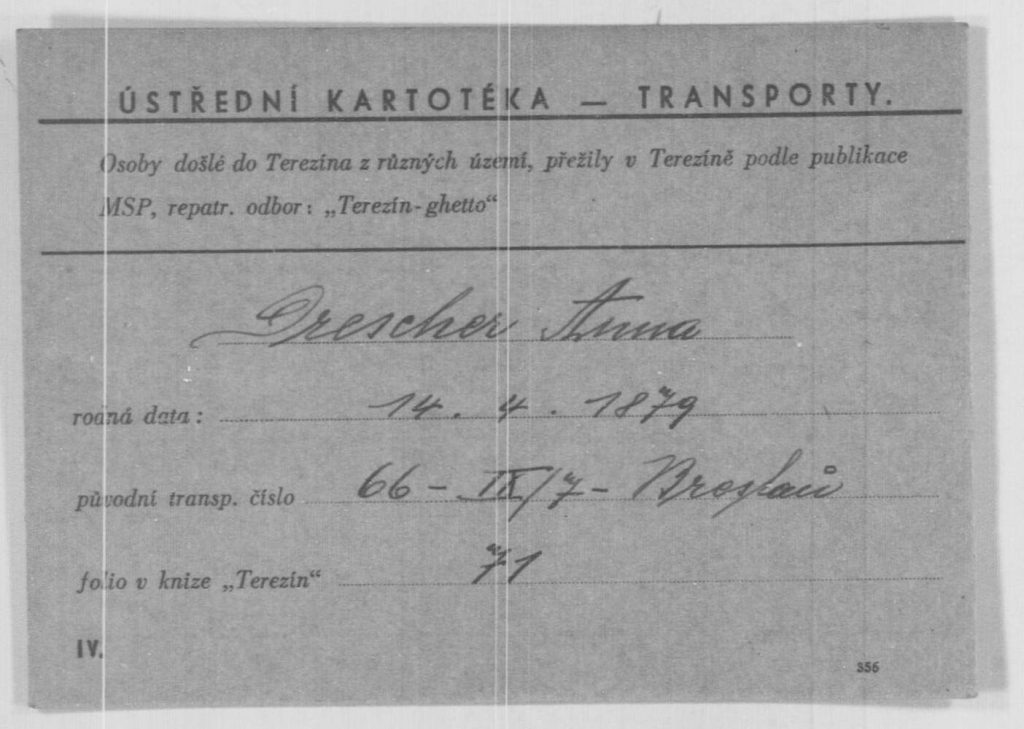

At least since December 1938, Anna was residing in Karpacz. In the following years, Nazi officials must have uncovered her Jewish roots because on January 8, 1944, she was sent to the Theresienstadt camp. Fortunately, the story has a happy ending because in 1946, Anna registered with Sharit haPlatah – the Central Committee of Liberated Jews in Bavaria.

Transport document for Anna Drescher to the Theresienstadt camp (Terezin) / Source: International Tracing Service, Bad Arolsen

Sources:

Końcowy raport składa się z kopi odnalezionych dokumentów, tłumaczeń, zdjęć oraz podsumowania. Wyjaśniam pokrewieństwo odnalezionych osób, opisuję sprawdzone źródła i kontekst historyczny. Najczęściej poszukiwania dzielone są na parę etapów i opisuję możliwości kontynuacji.

Czasem konkretny dokument może zostać nie odnaleziony z różnych przyczyn – migracji do innych wiosek/miast w dalszych pokoleniach, ochrzczenia w innej parafii, lukach w księgach, zniszczeń dokumentów w pożarach lub w czasie wojen. Cena końcowa w takiej sytuacji nie ulega zmienia, ponieważ wysiłek włożony w poszukiwania jest taki sam bez względu na rezultat.

Raporty mogą się od siebie mniej lub bardziej różnić w zależności od miejsca, z którego rodzina pochodziła (np. dokumenty z zaboru pruskiego, austriackiego i rosyjskiego różnią się od siebie formą i treścią).

Na podstawie zebranych informacji (Twoich i moich) przygotuję plan i wycenę – jeśli ją zaakceptujesz, po otrzymaniu zaliczki rozpoczynam pracę i informuję o przewidywanym czasie ukończenia usługi. Standardowe poszukiwania trwają około 1 miesiąca, a o wszelkich zmianach będę informować Cię na bieżąco.

Na Twoje zapytanie odpiszę w ciągu 3 dni roboczych i jest to etap bezpłatny. Być może zadam parę dodatkowych pytań, dopytam o cele albo od razu przedstawię propozycję kolejnych kroków.

Warto pamiętać, że im więcej szczegółów podasz, tym więcej rzeczy mogę odkryć.

Podziel się ze mną:

I najważniejsze – jeśli masz niewiele informacji, zupełnie się tym nie martw, w takich sytuacjach także znajdę rozwiązanie.