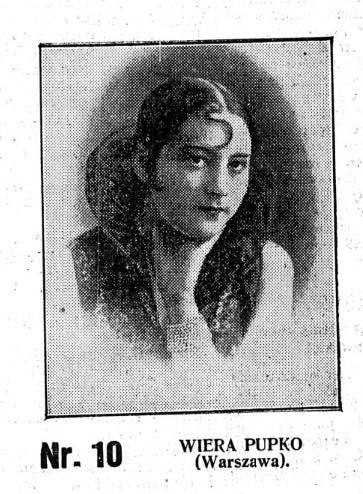

Wiera Pupko, a photo from the beauty pageant competition in “Nasz Przegląd” (Our Review), 1929.

“Miss Wiera Pupko (No. 10) asks us to note that, for reasons beyond her control, she is forced to withdraw from the competition.”

Wiera, affectionately called “Wieruszka” by her relatives, was born in 1907 in Lida as the daughter of Isaac Pupko and Maria (née Trakiner). Shortly after her birth, the family moved to Vilnius, and after World War I, they relocated to Warsaw. According to the recollections of her cousin, Irene Newhouse Pupko, Wiera’s parents sent her to Belgium to study vocational counseling. They, on the other hand, became trapped in Warsaw, from where, in August 1941, Wiera received the last postcard written by her father.

From left to right: Wiera Pupko with an unknown person,

Maria Pupko, née Trakiner, Wiera’s mother,

Isaac Pupko, Wiera’s father,

photos from the family collection of Irene Newhouse, née Pupko.

The last card Wiera received from her father from the Warsaw Ghetto, from the family collection of Irene Newhouse, née Pupko.

When deportations of Jews from Belgium began, Wiera managed to escape to Cuba, where she worked as a diamond cutter.

But how is that possible? To Cuba? During the war and without specialized education? It turns out that during the war, Cuba admitted 6,000 Jewish diamond cutters and their relatives fleeing from Belgium, and Wiera was among them.

Passenger list from Havana to Miami, Wiera Pupko is the last one on the list.

On May 3, 1948, Wiera arrived in the United States, where she married Emil Turnheim and started a new life. According to Irene’s memories, Wiera was interested in the lives of her relatives but was reluctant to delve into her own past. To any inquiries about her pre-war life, she would reply, “It should be enough that I say so.” When Irene started taking notes, Wiera fell silent and waited for her to put down the pen. In the end, Irene and her mother found a way to persuade her by bribing her with her favorite cornbread muffins.

Wiera Turnheim Pupko passed away in New York in 1989.

Sources:

Dąbrówka Children’s Home in Cieplice Śląskie-Zdrój / Photo by Marta Maćkowiak

At the end of the 19th century, the brothers Georg and Artur Barasch purchased a building with a restaurant and an English garden located on a hill known as Weinberg (Wine Mountain), now at ul. Podgórzyńska 6. In 1879, the hill belonged to Beata Oertel. Her daughter, Paulina Fuchs, sold the land to Mr. Kums, who constructed the aforementioned building, opened a restaurant named Offaschänke, and established the English garden. Later, the entire property was to be leased to a waiter named Schmidt, and at the end of the 19th century, it was sold to the Barasch brothers, the owners of the Warenhaus Gebrüder Barash department store in Breslau (currently: the Feniks department store in Wrocław).

The Barasch brothers carried out extensive renovations and established a holiday home for their employees, naming it Baraschheim.

Georg and Artur were born into a Jewish family in Ścinawa (Steinau an der Oder). Their first joint and successful business venture was the sale of Baratol shoe polish in their hometown. Their success encouraged them to expand their activities, and in 1896, they opened a store in Wrocław (Breslau). In 1904, they built the Warenhaus Gebrüder Barash department store (currently still existing under the changed name, as Feniks department store), and before World War I, they already had a network of department stores throughout Germany.

Georg and Arthur Barasch/ source: Erholungsheim Barasch bei Warmbrunn im Riesengebirge. (Polona)

What was the stay at Baraschheim like?

The employees of Artur and Georg could use the resort free of charge from May to September, and the possible duration of their stay depended on the length of their employment – anything from 5 days to 4 weeks. Round-trip transportation and meals were also covered by the Barasch brothers.

Artur’s son, Werner Barasch, recalls: ‘Dad bought a sanatorium in the mountains, in Cieplice Śląskie-Zdrój, where all the employees of the Barasch department store could enjoy all the amenities and free meals during their annual leave. It was an exceptional addition to their salary. Dad was proud that he could offer this to them.’

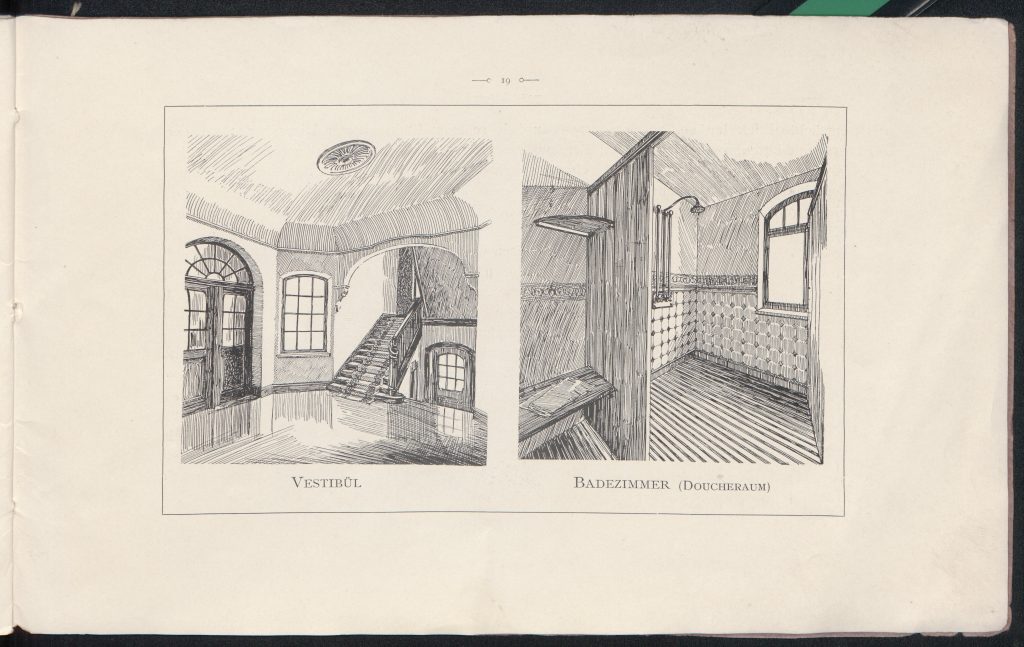

Interiors of Baraschheim / source: Erholungsheim Barasch bei Warmbrunn im Riesengebirge. (Polona)

Around 1920, the Barasch estate was purchased by Eugen Füllner, the owner of a paper machine factory in Cieplice (Bad Warmbrunn). In 1930, it was acquired by Friedrich Grössler, who renamed the holiday home to Eichenhof. In 1934, the building briefly became a sports school, and from 1935, it served as a military garrison. The complex was also called Das Deutsche Heim for some time.

After the Nazis came to power, Georg Barasch fled to Switzerland with his wife and son, later they moved to Ecuador. Artur died in Auschwitz on November 6, 1942, but fortunately, his wife and son managed to survive the war. In the following years, a Stolperstein (memorial stone) was placed in front of their villa, at Wissmannstrasse 11 in Berlin. Descendants of the Barasch brothers live in the United States and South America.

Between 1945 and 1961, the building served as a holiday home for the Polish Teachers’ Union. Presently, since 1961, the building functions as the Dąbrówka Children’s Home.

Sources:

The tenement at Pl. Piastowski 31 in Cieplice Śląskie Zdrój / Photo by Marta Maćkowiak

Joseph and Johanna had 7 children: two sons, Walter and Otto (the first passed away at the age of one, and the second son would later inherit his father’s textile business), and five daughters: Gertrud, Rosalie, Elsa, Henrietta, Margarethe, and Paula.

Photos from the building at Pl. Piastowski 31 in Cieplice Śląskie-Zdrój / Photo by Marta Maćkowiak

Advertisement for Joseph Engel’s store in Warmbrunner Nachrichten from 1910

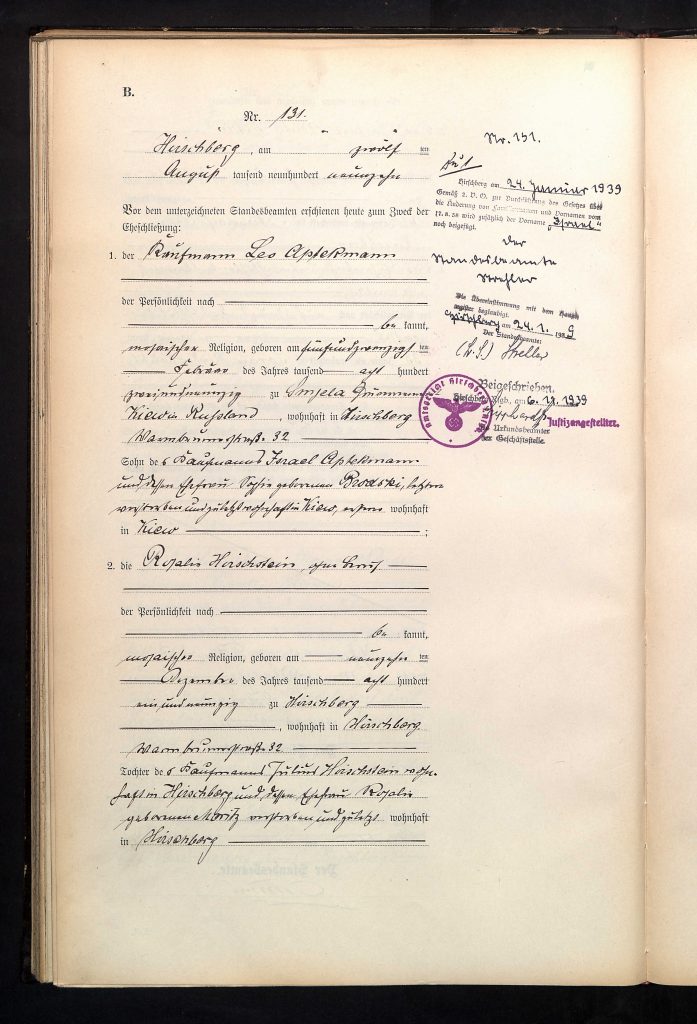

The first page of Margarethe Engel’s marriage certificate with a note regarding the adoption of the name Sara in accordance with the Nazi law – you can find more information about it in this article

The door to the building at Sybelstrasse 18 in Berlin and Stolpersteine commemorating Margarethe and Paula / Source: stolpersteine-berlin.de

Sources:

View of the Wilhelmshöhe villas from ul. Ludwika Hirszfelda / Photo by Marta Maćkowiak

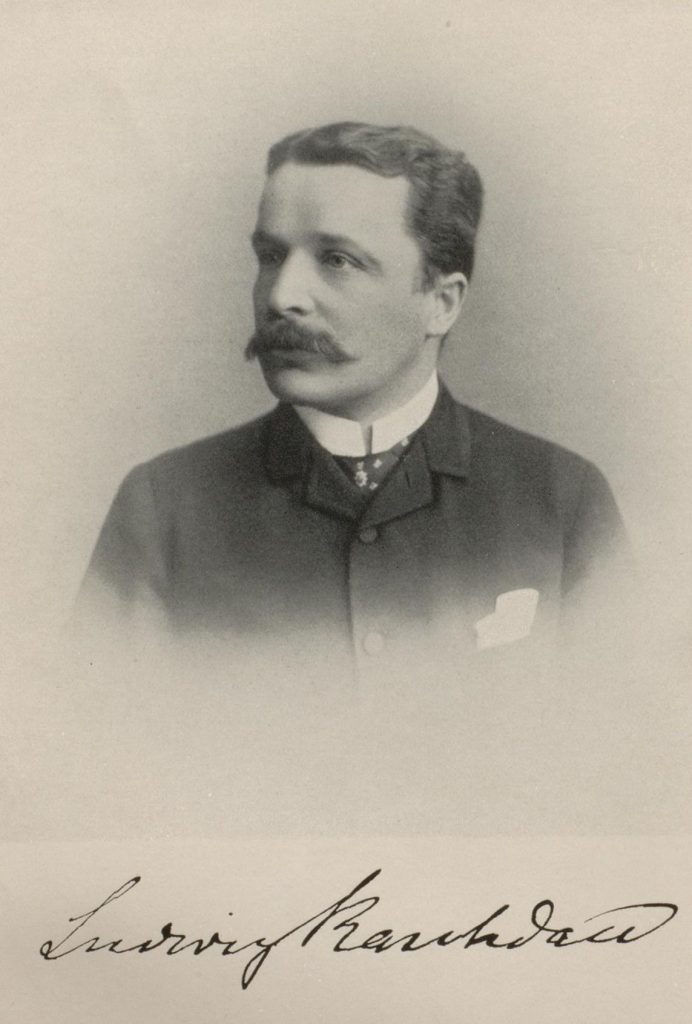

Ludwig Raschdau / source: Wikipedia

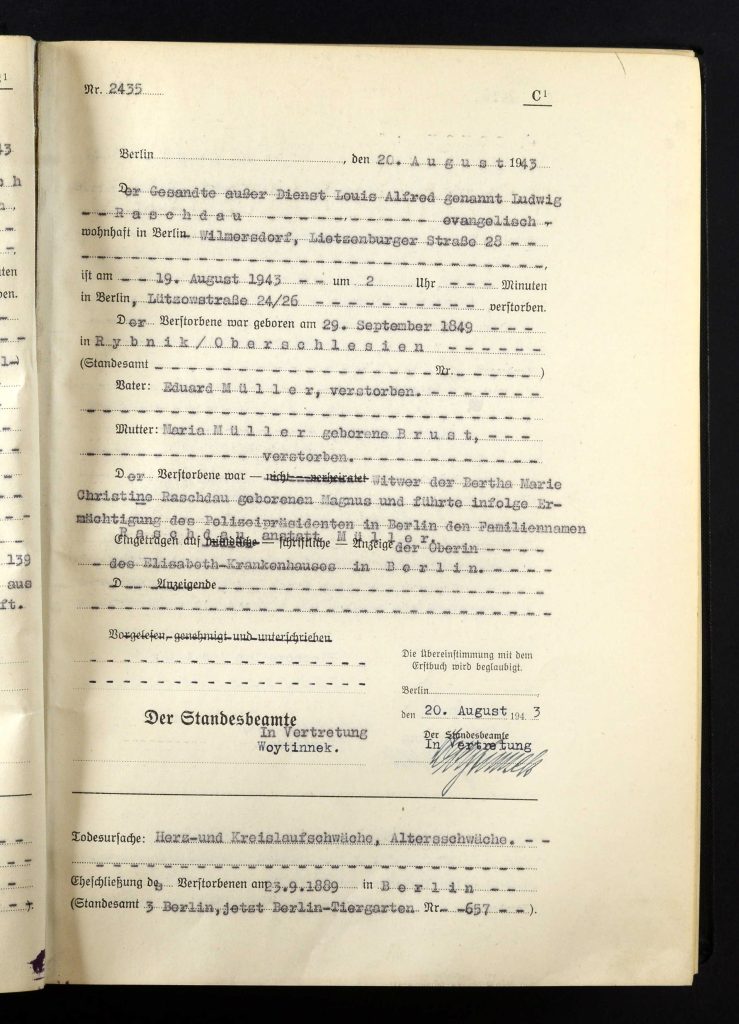

Death certificate of Christine Raschdau / source: Landesarchiv Berlin

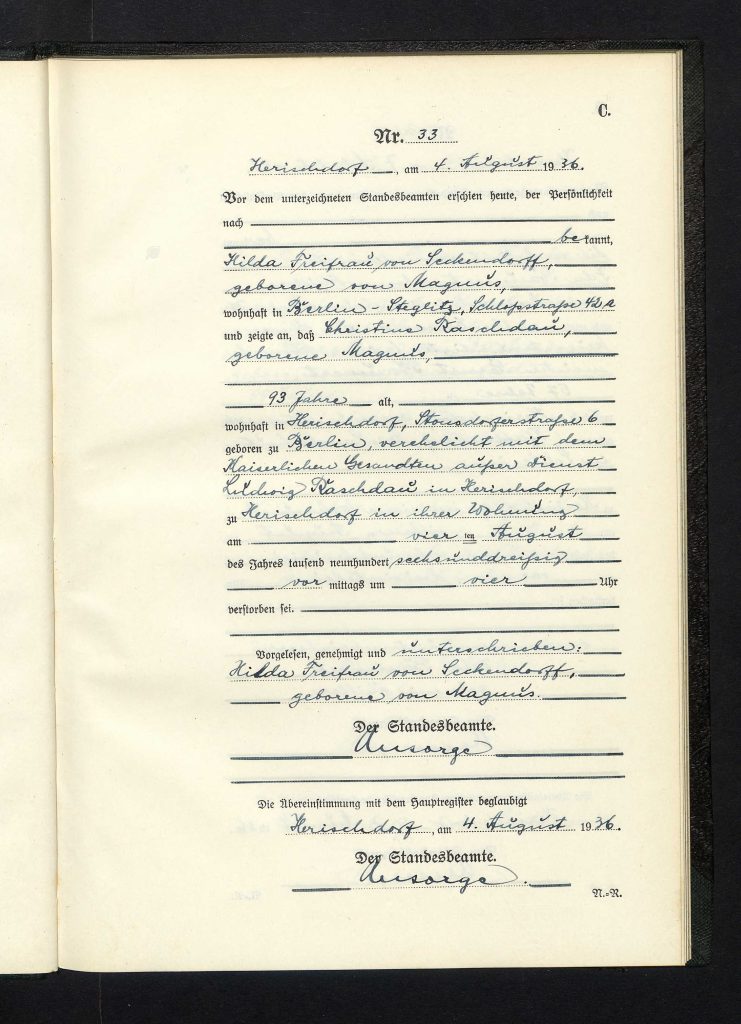

Death certificate of Ludwig Raschdau / source: Landesarchiv Berlin

After the war, the villas belonged to the Polish Red Cross, and there was a training and recreation center here. And today? The sight is heartbreaking.

View of the Wilhelmshöhe villas from ul. Ludwika Hirszfelda / Photo by Marta Maćkowiak

View of the villa in the past / source: Fotopolska.eu

“Marysieńka” at Plac Piastowski 33 in Cieplice Śląskie-Zdrój, where Rozalia Saulson wrote the guidebook / Photo by Marta Maćkowiak

Rozalia Saulson, the subject of today’s exploration, was born in 1807 in Łask as the daughter of the physician Abraham Juda Feliks and Fajga Filipina née Enoch, the daughter of a physician from Wieruszów. Rozalia had a sister named Hanna, and the family lived on the market square in Łask at house number 60.

Rozalia married twice. On November 1, 1826, in Łask, she married Jakub Juliusz Pauli, a doctor from Kępno, with whom she divorced after two years. Her second husband was Mikołaj Saulson, a merchant from Warsaw. There, Rozalia resided, charitably educated Jewish children, and flourished in the field of writing, especially in Polish, which she considered her native language.

In 1849, likely for health reasons, Rozalia came to Warmbrunn, today’s Cieplice Śląskie-Zdrój, where she spent three months at the Verein guesthouse – today’s “Marysieńka” at Piastowski Square 33. During this stay, she wrote the aforementioned guidebook „Warmbrunn i okolice jego w 38 obrazach zebranych w 12 wycieczkach przez Pielgrzymkę w Sudetach” (Warmbrunn and its surroundings in 38 pictures gathered in 12 excursions during a Pilgrimage in the Sudetes).

The first page of Rozalia Saulson’s guidebook “Warmbrunn and its surroundings in 38 pictures gathered in 12 excursions during a Pilgrimage in the Sudetes” / Source: Polona.pl

Rozalia’s husband, Mikołaj (Mordechaj) Saulson, son of Jehuda Lejba, died in Warsaw on June 10, 1858, and was buried in the Jewish cemetery on Okopowa Street in Warsaw.

A year later, there is a mention in Kurjer Warszawski about Mikołaj’s death, with information that the family lived on Leszno Street. However, according to the 1839 tariff, Mikołaj Saulsohn lived at ul. Franciszkańska 12 (mortgage number 1811).

Tombstone of Mikołaj Saulson at the Jewish cemetery in Warsaw / source: Fundacja Dokumentacji Cmentarzy Żydowskich w Polsce (Foundation for Documentation of Jewish Cemeteries in Poland)

Kurjer Warszawski 11.06.1859

Plaque commemorating the creation of the guidebook on the “Marysieńka” building in Cieplice Śląskie-Zdrój / Photo by Marta Maćkowiak

Sources:

Today’s protagonist is Mathilde Buttermilch – another of the seven individuals whose tombstones have been preserved in the Jewish cemetery in Jelenia Góra (Hirschberg), and whose life stories I want to bring closer. And this tale will be not only about Mathilde but also about her grandson, who gained fame at the age of 100. So, if you ever think you’re too old for something, remind yourself of Hans’s story. But first, let’s return to his grandmother.

Tombstone of Mathilde Buttermilch in the Jewish cemetery in Jelenia Góra / Photo by Marta Maćkowiak

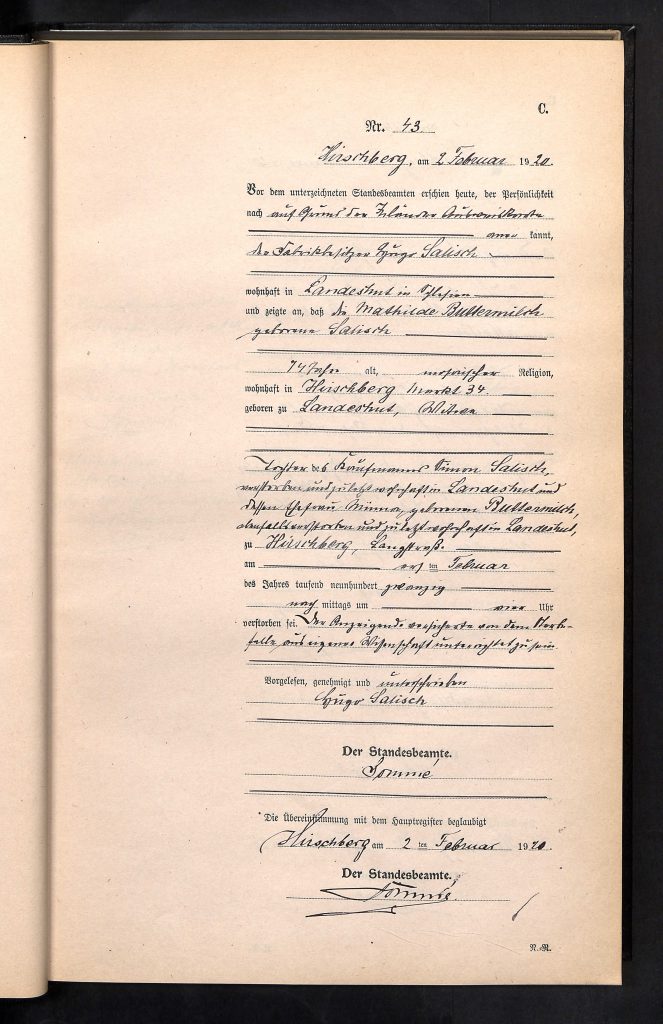

Death certificate of Mathilde Buttermilch / Source: Landesarchiv Berlin

On September 12, 1876, she married Alexander Buttermilch, a trader from Lissa (Leszno), the son of the late Jakob Buttermilch from Landeshut (Kamienne Góry) and Colina née Gottstein, who lived in Leszno before her death. Considering that Mathilde’s mother’s maiden name was Buttermilch and she came from Lissa, there is a high probability that the spouses were related within a certain generation.

Alexander and Mathilde settled in an apartment in the tenement house at Plac Ratuszowy 34 (Markt 34), which would remain their home until their deaths. Alexander passed away first, on March 3, 1907.

Plac Ratuszowy 34 in Jelenia Góra / Source: Polska-org.pl

Marriage certificate of Max Keilson and Elsa Buttermilch / Source: Landesarchiv Berlin

Photo of Hans Keilson / Photo by Herman Wouters for The New York Times

young Hans Keilson

Sources:

As I strolled down Łabska Street in Jelenia Góra (Hirschberg) for the first time, the house at number 12 immediately grabbed my attention. With its elegant driveway and richly adorned façade reminiscent of ancient temples, I recall my initial thought during that stroll: “Someone exceptional must have lived here.” And indeed, that proved to be true. Let me introduce you to the history of Villa Vestvali.

The house at ul. Łabska 12 in Jelenia Góra, formerly Villa Vestvali, later Villa Birken / Photo: Marta Maćkowiak

Information about Elise on the pre-war map of Cieplice

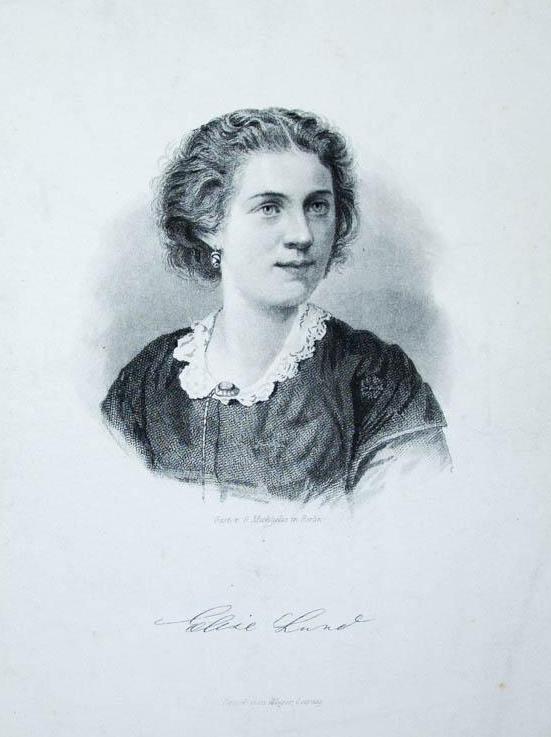

Portrait of Elise Lund – AbeBooks antique shop

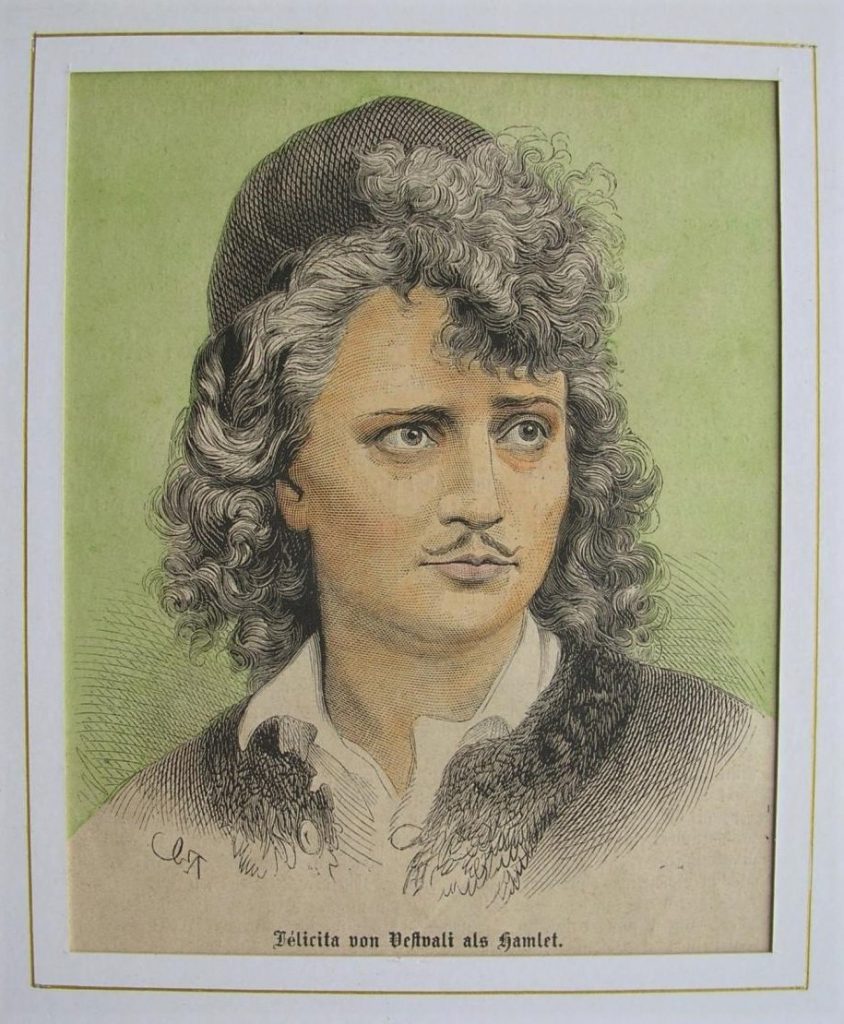

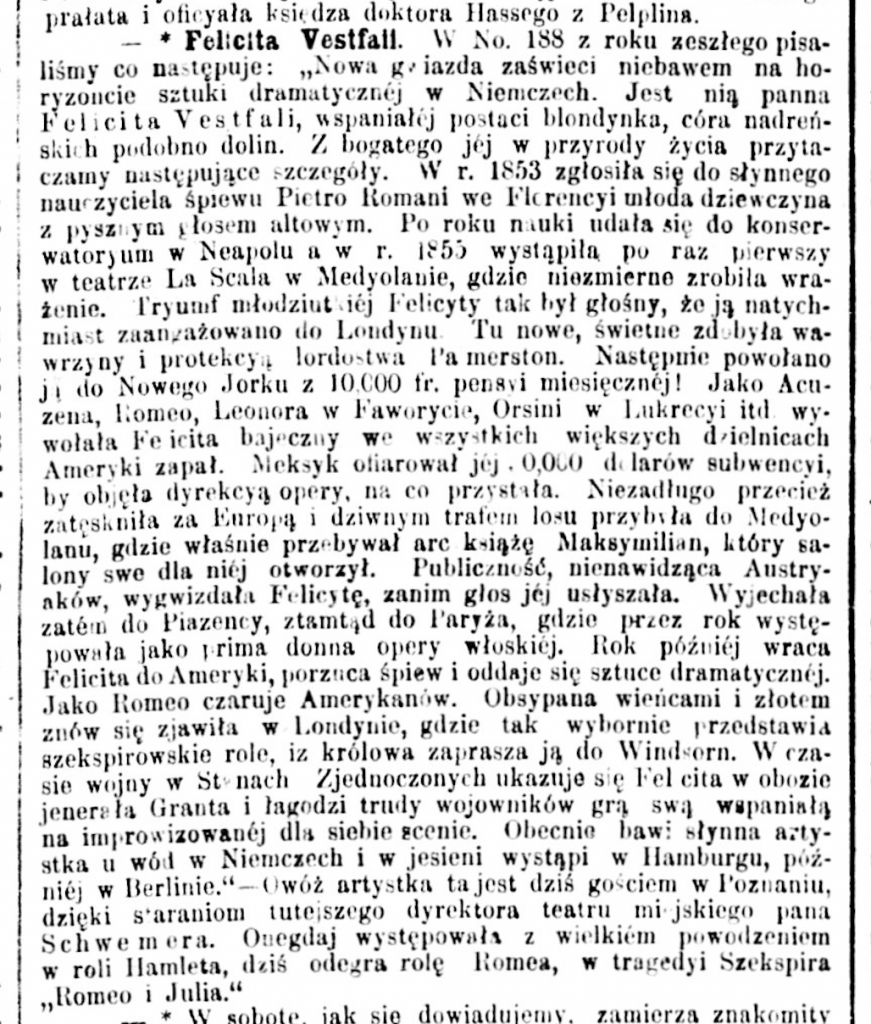

Felicita von Vestvali, according to various sources, was born either in Szczecin, Warsaw, or Krakow, in 1828 or 1831. Some claim she was German, while others say she was Polish. According to some, her name was Anne Marie Stagemann, while others refer to her as Felicja Westfalowicz. She was said to be the daughter of a high-ranking official, a noblewoman, or a fugitive from Polish lands.

And as the famous saying goes, there’s a grain of truth in every gossip. Piotr Szarota, a descendant of Felicity’s sister, Emma Spitzbarth (née Stagemann), who is working on a book about Vestvali’s life, has managed to establish a few facts.

Felicita was born in Szczecin (then German Stettin) in 1828 or 1829 as Maria Stagemann. Her parents were Prussian Army Lieutenant Georg Stagemann and Charlotte von Hünefeld.

The Stagemann family was related to the Polish Westwalewicz family, as Felicity’s half-brother was Henryk Westwalewicz, who later became her manager in the United States and adopted the nickname Henry Vestvali.

At the age of 15, Felicita, against her parents’ wishes, ran away from home disguised as a boy to join Wilhelm Bröckelmann’s theater troupe in Leipzig. Shortly thereafter, she was discovered by the actress Wilhelmine Schröder-Devrient, who became her mentor.

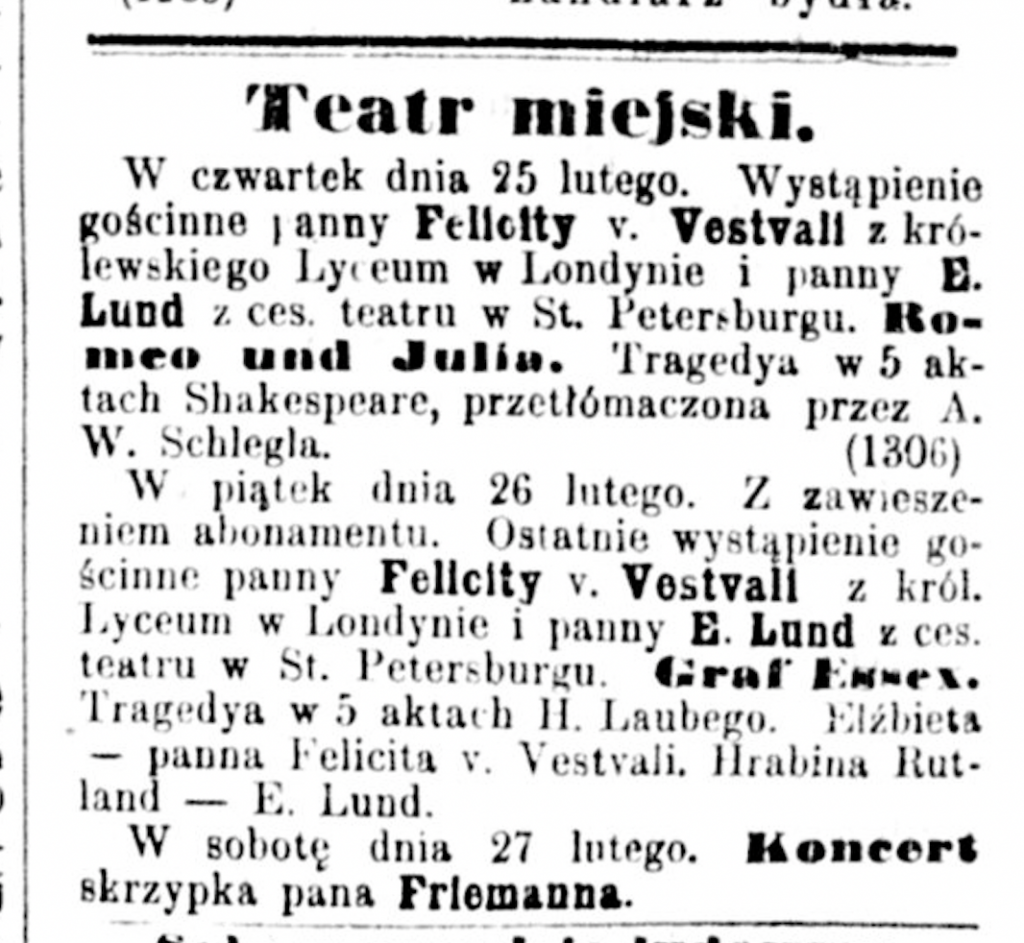

Information about the performance of Elise Lund and Felicity Vestvali as Romeo and Juliet in Poznań. Dziennik Poznański, February 26, 1869.

Felicita Vestvali / source: Bibliothèque nationale de France

Felicita made a striking impression on everyone, as Anna Dżabagina wrote, quoting Lilian Eriksson: “many beautiful women sought Vestvali’s favor, and many husbands had reason to envy the beautiful and charming Romeo.”

She was the first woman to play Hamlet, earning rave reviews, and she was a favorite of, among others, Abraham Lincoln and Napoleon III, from whom she received a silver suit of armor as a gift.

Dziennik Poznański, February 26, 1869 – Felicita Vestvali

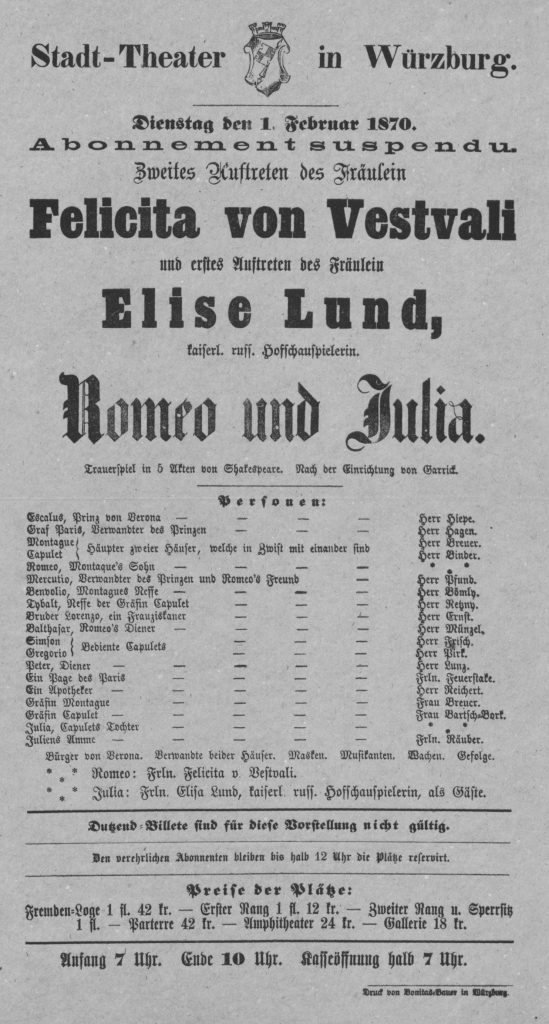

Joint performance of Felicity and Elise as Romeo and Juliet

After the end of the Franco-Prussian War in 1871, Felicita performed less frequently and decided to focus on her private life. She found her place in Bad Warmbrunn, today’s Cieplice Śląskie-Zdrój (a district of Jelenia Góra), where she bought a plot of land and commissioned the construction of a villa. Moreover, Felicita engaged in real estate speculation and created an entire neighborhood called Russische Kolonie (Russian Colony) in the present-day vicinity of Łabska and Krośnieńska streets. According to one theory, the name originated from the popularity among Russian spa guests. According to the Historical Maps Atlas, the first villa in the Russian colony belonged to Mrs. von Spitzbarth, the wife of a financial counselor, who was said to be of Russian origin.

It is highly likely that it pertained to Emma Spitzbarth nee Stegemann, the sister of Felicity, who also owned land there. Emma lived in Warsaw, where she is buried in the Evangelical-Augsburg Cemetery. She was the mother of Warsaw architect Arthur Otto Spitzbarth and the grandmother of the writer Eleonora Kalkowska.

The Spitzbarth family tomb at the Evangelical Augsburg Cemetery in Warsaw / Source: Grobonet.com

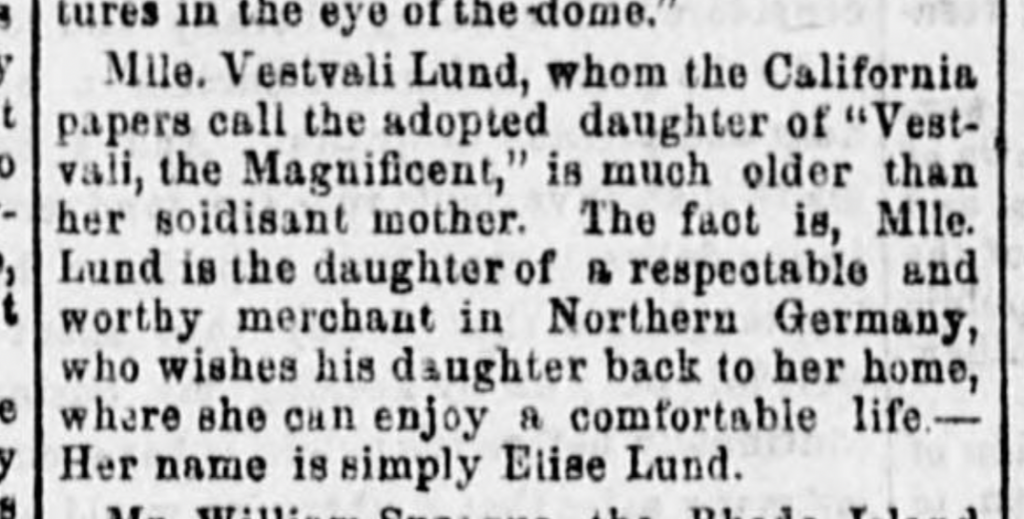

Snippet about Elise not being able to be Felicity’s adopted daughter because she was older / Columbus Morning Journal, January 23, 1866

Felicita Vestvali passed away on April 3, 1880, either during a visit to her sister in Warsaw or already in Bad Warmbrunn (Cieplice). Towards the end of her life, she was associated with another woman (referred to as G. in letters), but it was Elise Lund who inherited her villa on Łabska Street and the majority of her estate. Elise was also supposed to fulfill her final wish and bring Felicity’s body to Cieplice for burial.

And what if she became the patron of a special place in Cieplice? What would you suggest?

Sources:

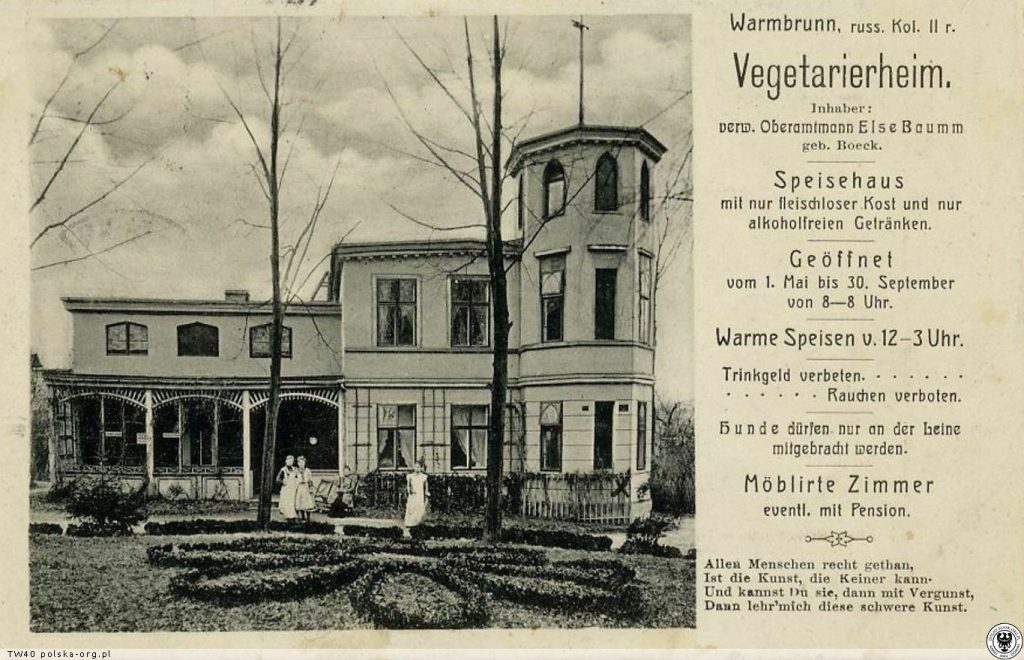

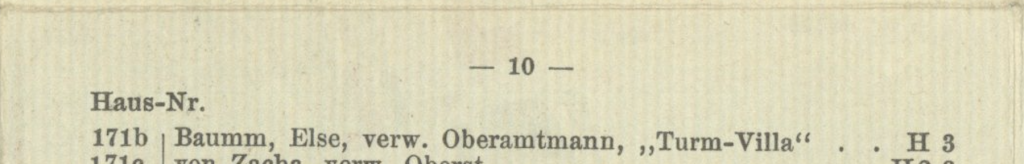

Out of love for Malinnik, once a village called Herischdorf, annexed to Bad-Warmbrunn (today’s Cieplice Śląskie-Zdrój) before the war, I have created a special series dedicated to the beautiful villas in this area and their stories. I begin with the villa located at ul. Łabska 4, formerly Tannenberg 6 (and before World War I, Russische Kolonie), called Turm Villa and Vegetarierheim.

Postcard of the villa located at Tannenberg 6 (Russische Kolonie), today ul. Łabska 4 in Jelenia Góra (Hirschberg) / Source: polska-org.pl

Information about Elsa on the pre-war map of Cieplice

At Vegetarierheim, they exclusively served vegetarian meals and non-alcoholic beverages. Smoking was, of course, prohibited. It was a truly comprehensive cleansing treatment, especially for those times.

And the villa had a wonderful motto in its advertisement:

Today, the building is a multi-family home.

The houses in Malinnik are beautiful, each of them unique and majestic, each hiding a special story. Almost each one belonged to barons, generals, officials holding higher positions, and factory owners.

Photo of the villa at ul. Łabska 4 in Jelenia Góra (Cieplice Śląskie-Zdrój) / photo by Marta Maćkowiak

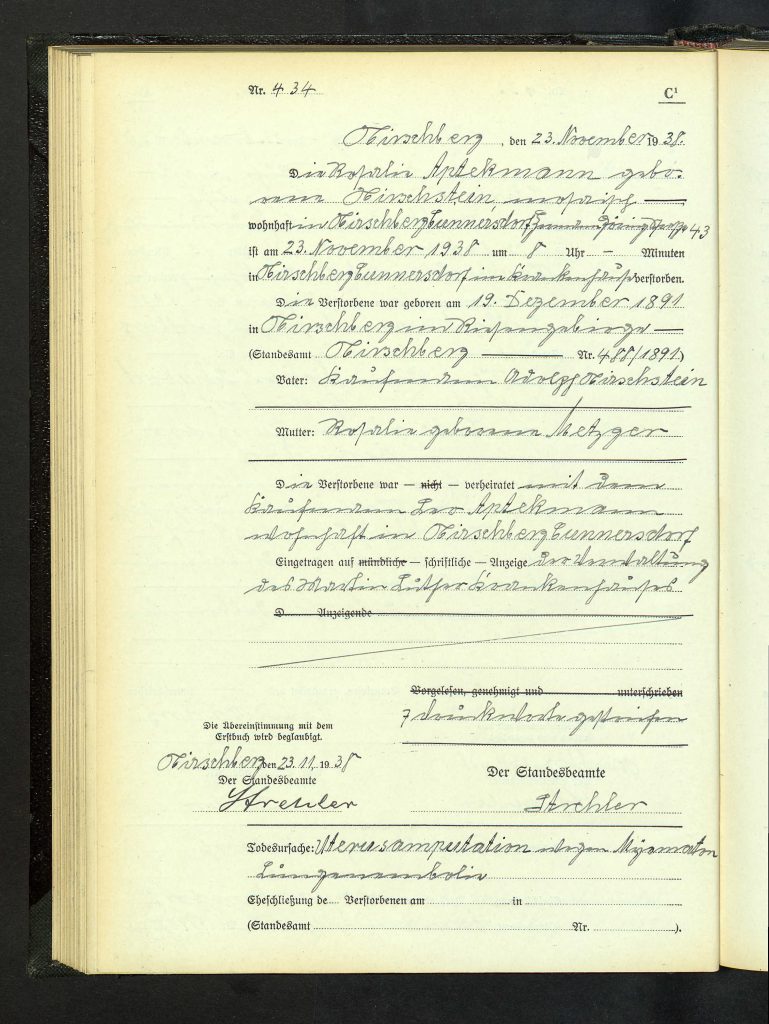

Today is the anniversary of Rosel Aptekmann’s death, so her story will be the first in a series dedicated to people buried in the Jewish cemetery in Jelenia Góra (Hirschberg). Only a few tombstones with readable inscriptions have survived, just seven in total. Let’s learn about Rosel Aptekmann.

The gravestone of Rosel Aptekmann at the Jewish cemetery in Jelenia Góra / Photo: Marta Maćkowiak

On November 23, 1938, Leo Aptekmann came to the Civil Registry Office to report the death of his wife. Rosalie passed away on the same day at the age of 46 in the Martin Luther Evangelical Hospital in Jelenia Góra (formerly Hirschberg-Cunnersdorf). Presently, the building houses a Caritas care and medical facility (located at ul. Żeromskiego 2).

Two weeks after Kristallnacht. Perhaps this event had an impact on her health.

Rosalie Aptekmann’s death certificate / Source: Landesarchiv Berlin

Former Martin Luther Evangelical Hospital in Jelenia Góra, now Caritas care and medical facility at ul. Żeromskiego 2 / Source: Polska-org.pl

Leo and Rosalie lived at Hermann Göringstrasse 43 (formerly, before 1933, Warmbrunnerstrasse, now ul. Wolności), 600 meters from the hospital. According to available sources, it seems that the numbering of buildings has not changed.

The building on ul. Wolności (formerly Warmbrunnerstrasse/Hermann Göringstrasse) in Jelenia Góra / Source: Polska-org.pl

The building at ul. 43 Wolności 43 in Jelenia Góra today / Photo by Marta Maćkowiak.

The Aptekmanns were married for just under two decades, having tied the knot in Jelenia Góra on August 12, 1919.

Leo Aptekmann arrived in Jelenia Góra from Ukraine, specifically from the city of Smila, where he was born on February 25, 1892, as the son of Israel Aptekmann, a merchant, and Sophie née Brodski, residents of Kiev.

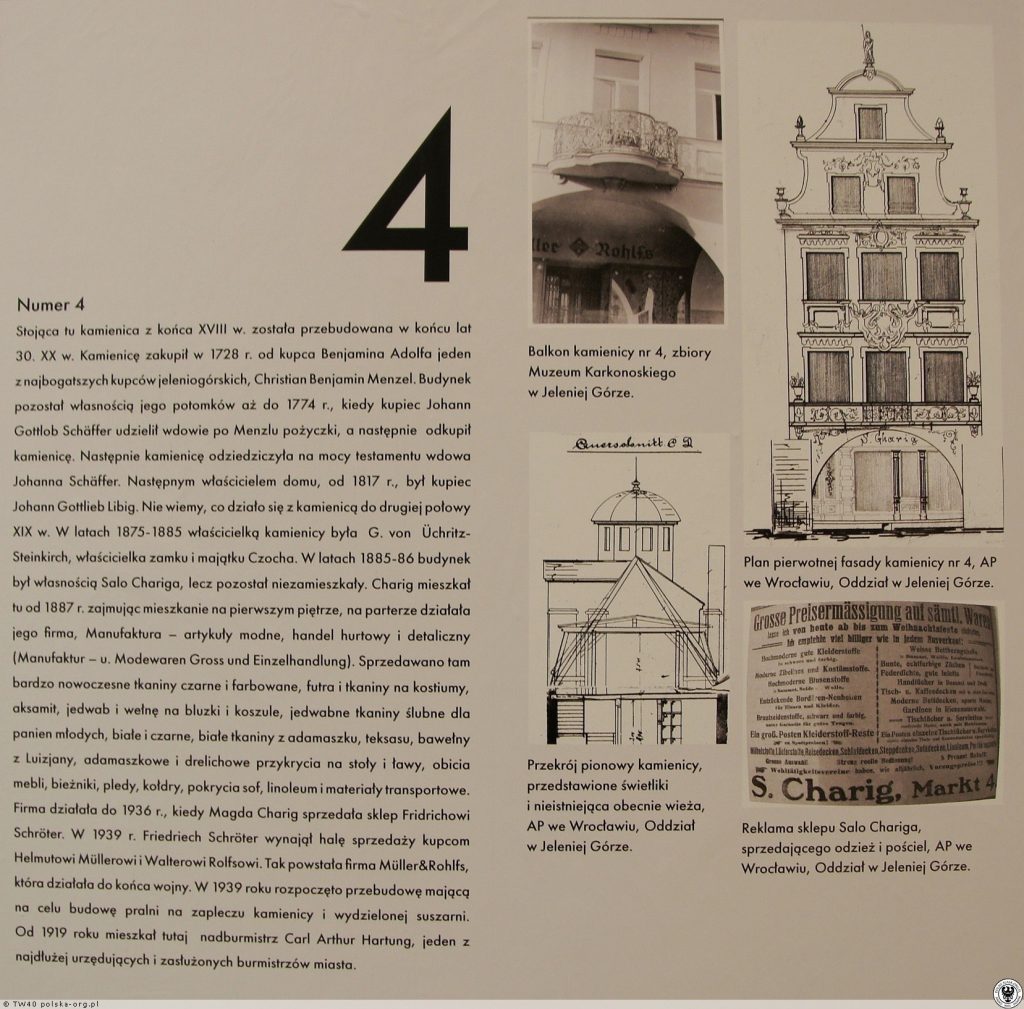

Rosalie, née Hirschstein, came into the world in Jelenia Góra on December 19, 1891, as the daughter of Julius Adolph Hirschstein, a merchant, and Rosalie née Moritz, who lived in Jelenia Góra in a house at plac Ratuszowy 4.

Leo and Rosalie initially resided at today’s ul. Wolności 32, in a house adorned with David’s stars on the veranda. Today, in addition to apartments, there is a shop and a Pentecostal church at that location.

Building at ul. Wolności 32 in Jelenia Góra / Photo: Marta Maćkowiak

Tenement at plac Ratuszowy 4 in Jelenia Góra, fragment from the exhibition at the Karkonosze Museum / Source: polska-org.pl

Marriage certificate of Julius Hirschstein and Rosalie Moritz in Mainz / Source: Mainz City Archive

It is unknown whether Leo and Rosalie Aptekmann had any descendants. So far, I haven’t come across any trace of them, and it is also unclear whether Leo remarried.

However, it is certain that after Rosalie’s death, her husband lived for some time at Jägerstrasse 6 (today ul. Wyczółkowskiego) until he was deported and killed at Majdanek concentration camp.

Building at ul.Wyczółkowskiego 6 in Jelenia Góra / Photo: Marta Maćkowiak

Sources:

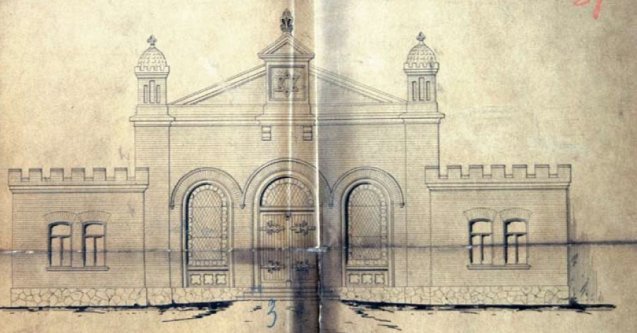

The Jewish community in Jelenia Góra (formerly Hirschberg) was quite modest, with a peak population of only 450 people. Nevertheless, the city had two Jewish cemeteries.

New Jewish Cemetery in Jelenia Góra on Sudecka Street / Photo by Marta Maćkowiak

The first, so-called “old” cemetery, was established between 1818 and 1820 in the vicinity of Nowowiejska, Na Skałkach, and Studencka streets. Today, there is no trace of this cemetery. No tombstones or cemetery architecture have been preserved, and a public square now stands in its place. After the resolution to close the cemetery was adopted by the City Council Presidium in Jelenia Góra in 1957, the liquidation process began in 1961.

Map of Jelenia Góra featuring the marked location of the old Jewish cemetery / Source: Fotopolska.eu

Photograph, likely depicting remnants of the old Jewish cemetery according to Fotopolska users, year 1928 / Source: Fotopolska.eu

Facing the street stood a beautiful mortuary building, which was set on fire during Kristallnacht in 1938. Surprisingly, the structure survived the war, and until 1972, it was inhabited by Leon and Maria Grzybek, the caretakers of the area. The Grzybek couple, quite fittingly named (Grzyb means ‘mushroom’ in Polish), tragically died due to mushroom poisoning. The cemetery was ultimately closed almost 100 years after its establishment, in 1974. The last burial in this building took place in 1959, and at that time, the Jewish community in Jelenia Góra consisted of 20 families.

Mortuary building at the Jewish cemetery in Jelenia Góra / Source: Okruchy z historii Żydów na Śląsku (Fragments from the history of Jews in Silesia), Warsaw 2014 via cmentarze-zydowskie.pl

Mortuary building at the Jewish cemetery on Sudecka Street in Jelenia Góra / Source: Polska-org.pl

Mortuary building at the Jewish cemetery in Jelenia Góra – building in the bottom right corner / Source: Polska-org.pl

Today, one part of the cemetery serves as a parking lot. Along the sidewalk, likely on the site of the mortuary, there is a boulder with a commemorative plaque, and further back, you can find several well-preserved tombstones.

Seven of them have been deciphered, and each will be the subject of a dedicated article: Rosel Aptekmann, Mathilde Buttermilch, Wilhelmine Danziger, Betty Ucko, Herman Cohn, Fritz Singer, and Leon Goldgraber, a representative of the post-war Polish community.

“The bitter death will not separate love” – inscription on one of the tombstones at the Jewish cemetery on Sudecka Street in Jelenia Góra.

Sources:

Końcowy raport składa się z kopi odnalezionych dokumentów, tłumaczeń, zdjęć oraz podsumowania. Wyjaśniam pokrewieństwo odnalezionych osób, opisuję sprawdzone źródła i kontekst historyczny. Najczęściej poszukiwania dzielone są na parę etapów i opisuję możliwości kontynuacji.

Czasem konkretny dokument może zostać nie odnaleziony z różnych przyczyn – migracji do innych wiosek/miast w dalszych pokoleniach, ochrzczenia w innej parafii, lukach w księgach, zniszczeń dokumentów w pożarach lub w czasie wojen. Cena końcowa w takiej sytuacji nie ulega zmienia, ponieważ wysiłek włożony w poszukiwania jest taki sam bez względu na rezultat.

Raporty mogą się od siebie mniej lub bardziej różnić w zależności od miejsca, z którego rodzina pochodziła (np. dokumenty z zaboru pruskiego, austriackiego i rosyjskiego różnią się od siebie formą i treścią).

Na podstawie zebranych informacji (Twoich i moich) przygotuję plan i wycenę – jeśli ją zaakceptujesz, po otrzymaniu zaliczki rozpoczynam pracę i informuję o przewidywanym czasie ukończenia usługi. Standardowe poszukiwania trwają około 1 miesiąca, a o wszelkich zmianach będę informować Cię na bieżąco.

Na Twoje zapytanie odpiszę w ciągu 3 dni roboczych i jest to etap bezpłatny. Być może zadam parę dodatkowych pytań, dopytam o cele albo od razu przedstawię propozycję kolejnych kroków.

Warto pamiętać, że im więcej szczegółów podasz, tym więcej rzeczy mogę odkryć.

Podziel się ze mną:

I najważniejsze – jeśli masz niewiele informacji, zupełnie się tym nie martw, w takich sytuacjach także znajdę rozwiązanie.