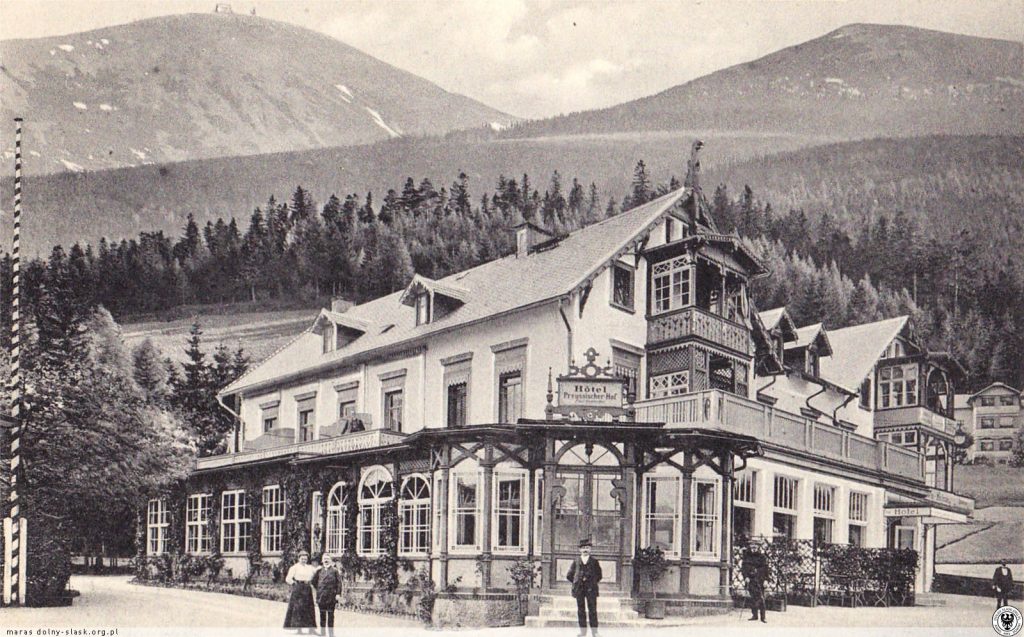

Chrobry Recreation House – now a ruin, once the Preussischer Hof hotel. Located 711 meters above sea level, with excellent cuisine, situated directly by the forest. As it turns out, it also served as a meeting place for members of the local Masonic lodge.

Chrobry Recreation House in Karpacz (formerly Hotel Preussischer Hof in Krumhubbel) / Photo by Marta Maćkowiak

Chrobry Recreation House in Karpacz (formerly Hotel Preussischer Hof in Krumhubbel) / source: Polska-org.pl

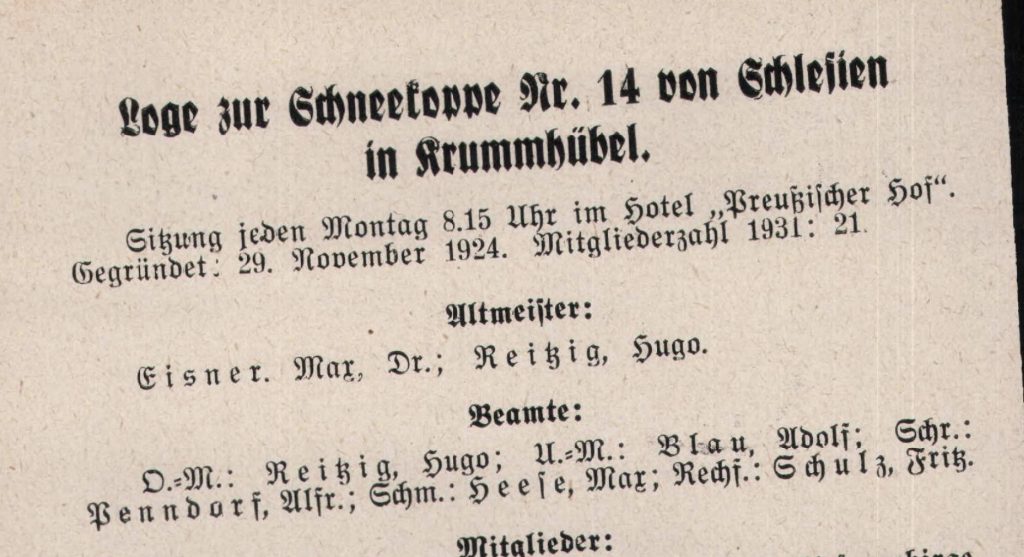

Loge zur Schneekoppe, or Lodge beneath the Śnieżka. Preussischer Hof, known as Chrobry after the war, was the weekly meeting place for members of the Carpathian lodge, gathering every Monday at 8:15 pm.

The Lodge was founded on November 29, 1924, and by 1931, it had 21 members.

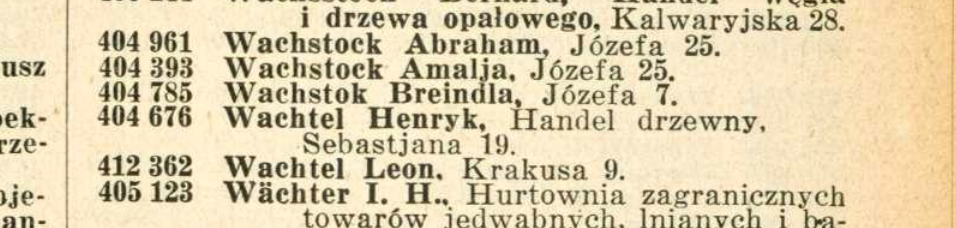

Fragment of the list of members of the Masonic Lodge in Karpacz

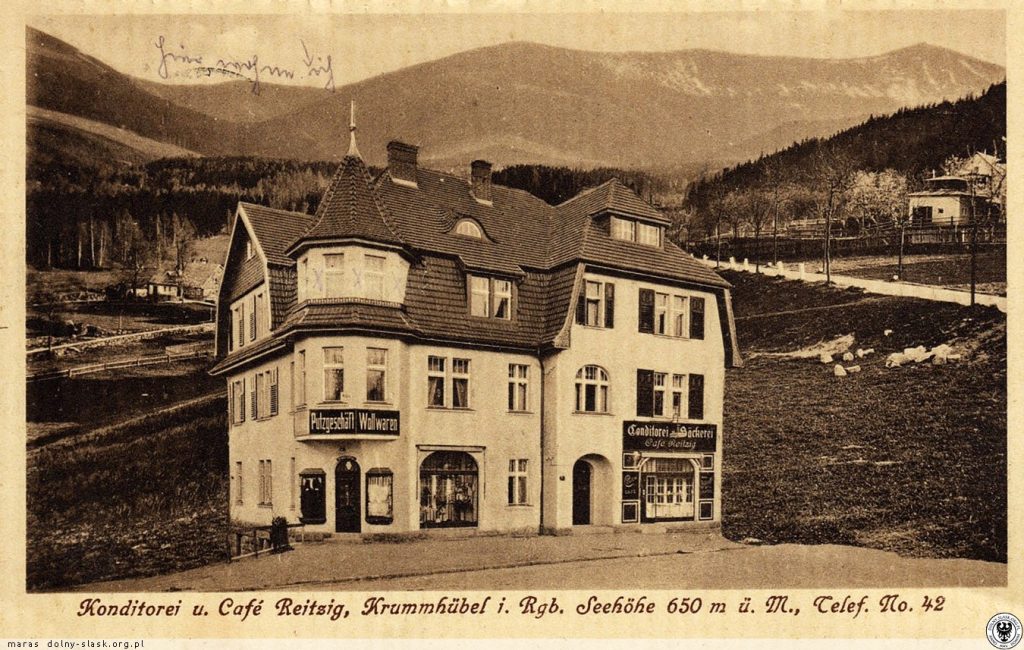

The building of the former confectionery and café owned by Hugo Reizig, today ul. Obrońców Pokoju 1 in Karpacz / Source: Polska-org.pl

The interior of the former confectionery and café owned by Hugo Reizig, today at ul. Obrońców Pokoju 1 in Karpacz / Source: Polska-org.pl

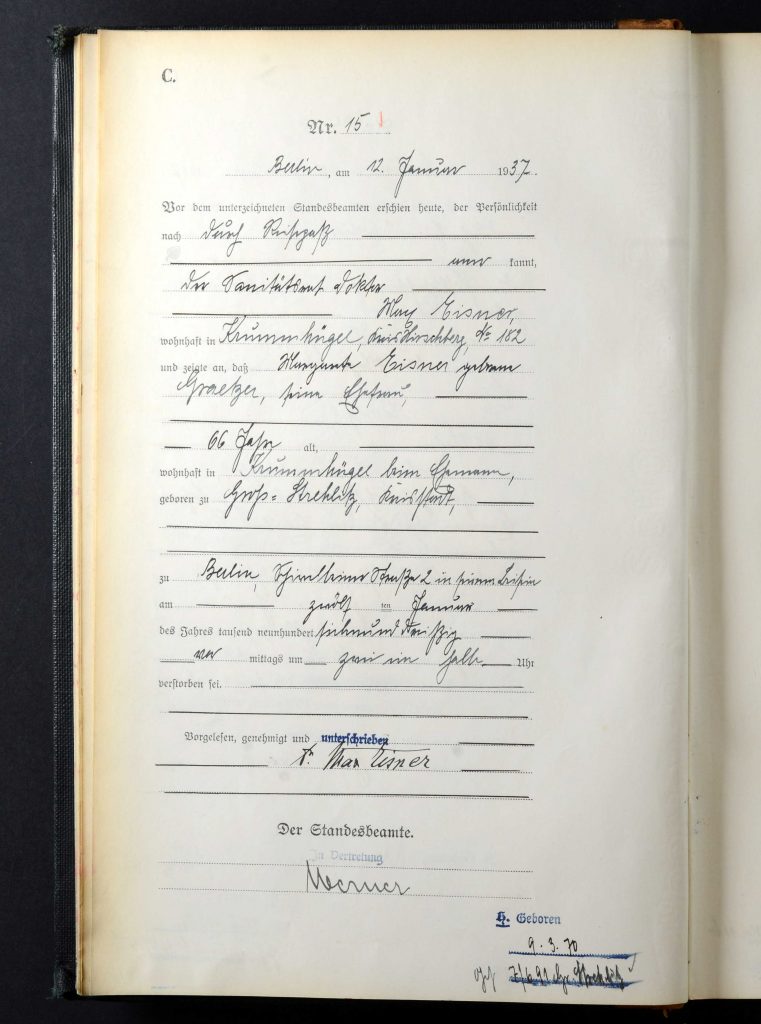

Death certificate of Margarete Eisner / Source: Landesarchiv Berlin

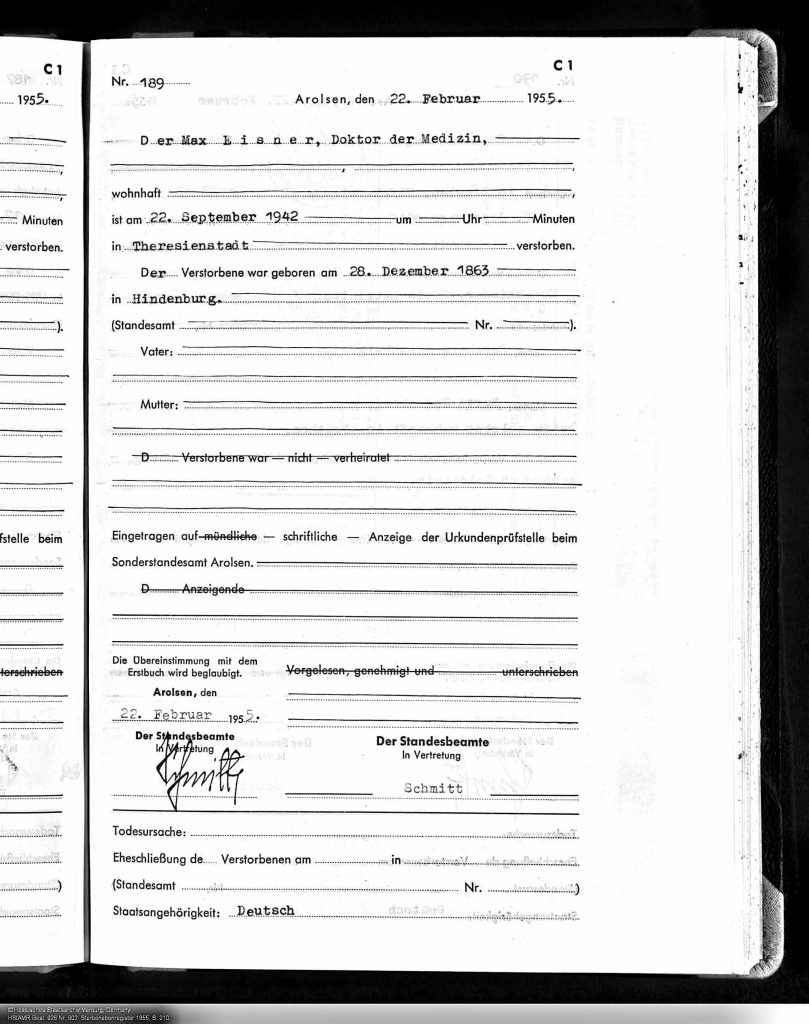

Death certificate of Max Eisner

Sources:

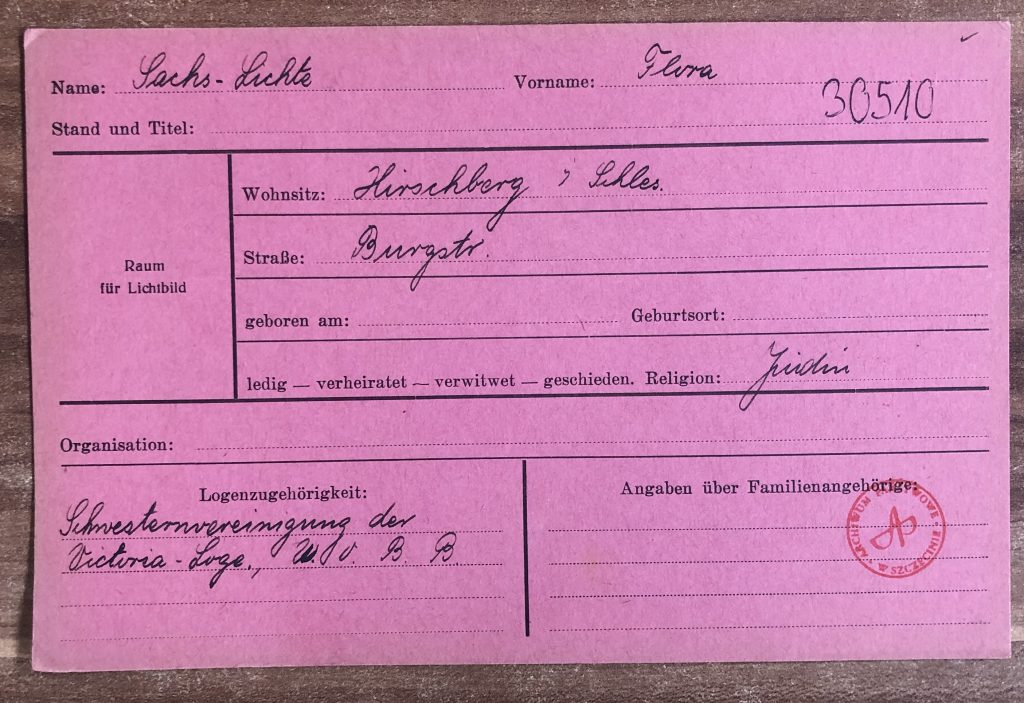

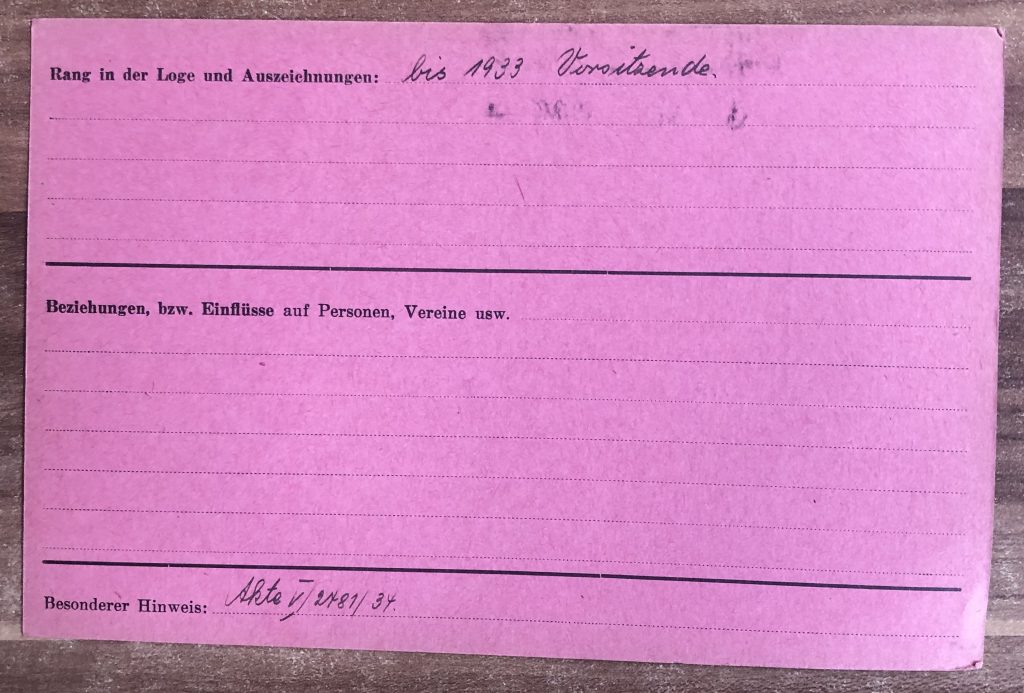

During my August visit to the State Archives in Szczecin, I came across an interesting collection – a file of Masonic lodge members compiled by the Main Security Office of the Reich from 1939 to 1945. In this collection, I found the record of a woman a Jewish woman from Jelenia Góra (Hirschberg), Flora Sachs, who served as the chairwoman of the Sisters Association of the Victoria Lodge.

Card of Flora Sachs from the file of Masonic lodge members / Photo: Marta Maćkowiak, State Archives in Szczecin

The main headquarters of Victoria Loge was located in Goerlitz (specifically at Bismarckstrasse 13), and contrary to common belief, its activities did not revolve around esoteric knowledge. Instead, it primarily focused on educating about Judaism and promoting values such as tolerance, goodness, and humanity.

According to the aforementioned card, Flora lived precisely at Lichte Burgstrasse 21 in Hirschberg, which is now Jasna Street in Jelenia Góra.

Parents of Flora Sachs née Nathan – Adolf Nathan and Lina née Cohn / Photos courtesy of Mr. Stephen Anthony Giesswein

Birth certificate of Flora Sachs / Source: Bundesarchiv in Berlin

The no longer existing tenements on Lichte Burgstrasse (today’s Jasna Street) in Jelenia Góra / Source: Polska-org.pl

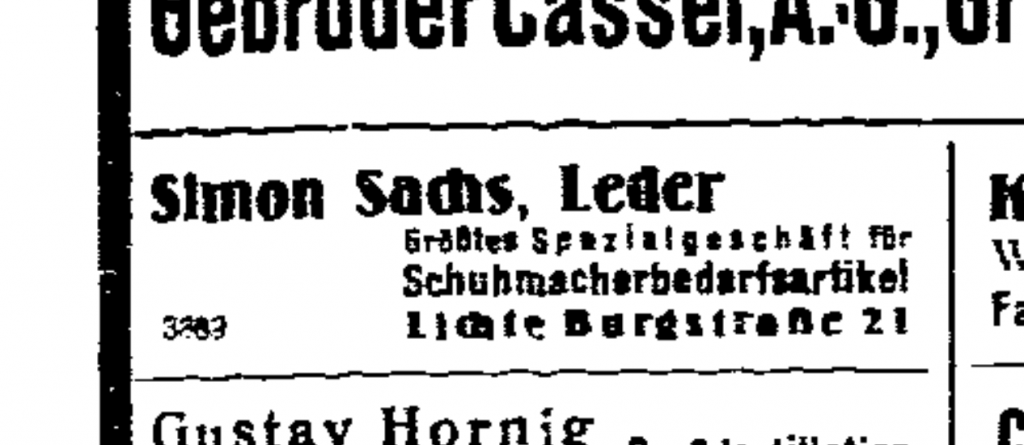

The Sachs family also ran a business here, specializing in tanning leather and trading leather goods, while Simon served as a member of the Jewish community board in Jelenia Góra.

Advertisement of Simon Sachs in the Arbeiter Zeitung, 1931

Cards of Flora and Simon from the Theresienstadt camp.

Statement of Flora’s death posted by her sister / Source: Yad VaShem

One page of the passenger list featuring Lothar and Hildegarde Sachs. They departed from Hamburg on June 29, 1938.

Statement of intent by Lothar Sachs, son of Flora and Simon, regarding becoming a U.S. citizen.

Sources:

When visiting the state archives in search of specific documents, I like to order ‘random’ folders to see if similar records might come in handy in the future. It’s like a lottery – sometimes I browse through hundreds of boring listings and calculations, and at other times, I discover incredible stories. One of those incredible stories is undoubtedly the story of Anna Drescher.

Villa Birkenhain in Krummhübel (presently Brzozowy Sad in Karpacz), ulica Sadowa 2 / źródło: Polska-org.pl

This time, I took on a folder concerning Judenvermögensabgabe, which can be translated as the Jewish Property Tax. Judenvermögensabgabe was a tax introduced on November 12, 1938, and it applied to every German Jew whose property was valued at a minimum of 5,000 marks. This tax was also referred to as the ‘penance tax’ because, after the assassination of the German Embassy Secretary Ernst Eduard vom Rath on November 7, 1938, by Herschel Grynszpan, a Polish-German Jew, Hermann Göring demanded the payment of one billion German marks as ‘penance’ for the damage caused to the German nation by Jews.

While reviewing case after case, my attention was drawn to Anna Drescher, who, in 1938, was residing in Villa Birkenhein in Krummhübel – today’s Brzozowy Gaj guesthouse located in Karpacz at ul. Sadowa 2.

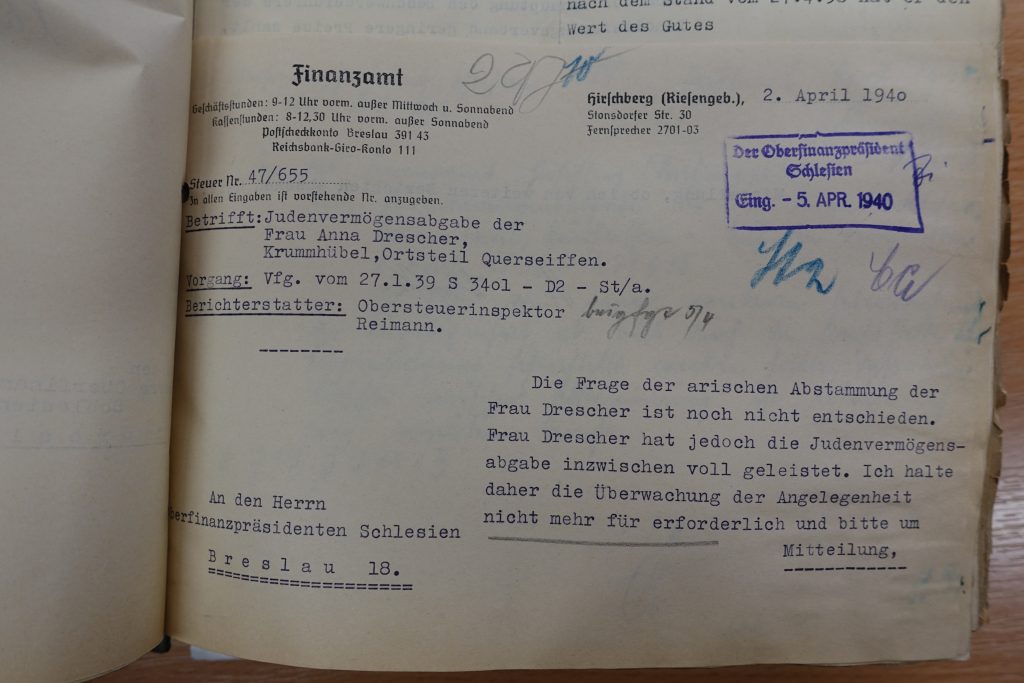

The first page of the folder: “The question of Mrs. Drescher’s Aryan origin has not yet been resolved” – so let’s see what this is about.

Page regarding Judenvermögensabgabe and Anna Drescher / Source: State Archive in Wrocław

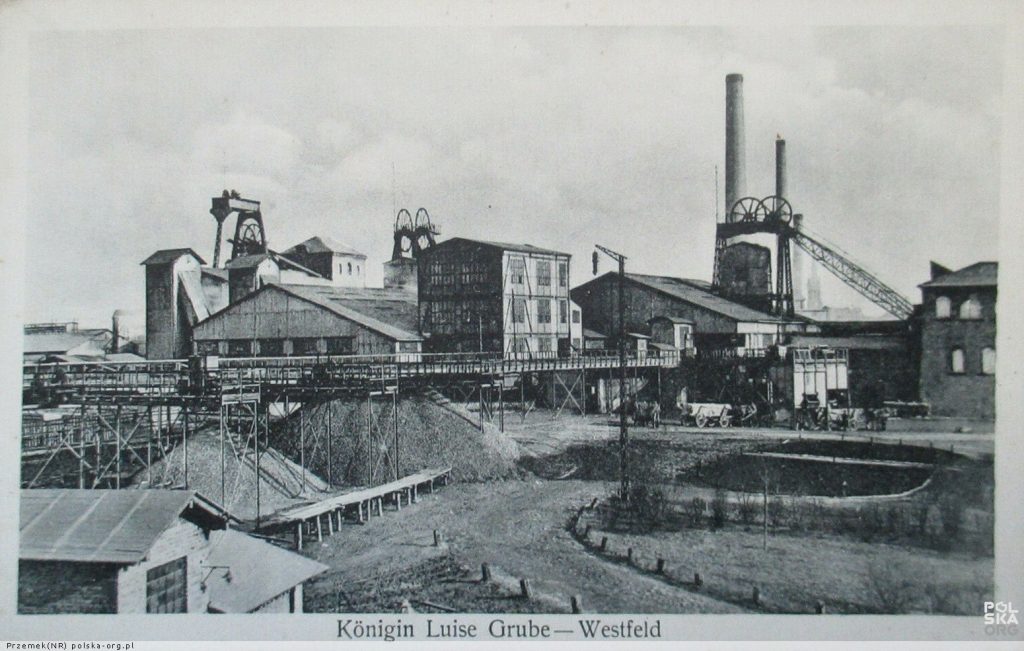

Queen Luiza Mine in Zabrze, 1920s-1930s / Source: Polska-org.pl

Fragment of the birth certificate of Franz Drescher and Anna Toeplitz’s daughter, along with information about their religion / Source: Landesarchiv Berlin

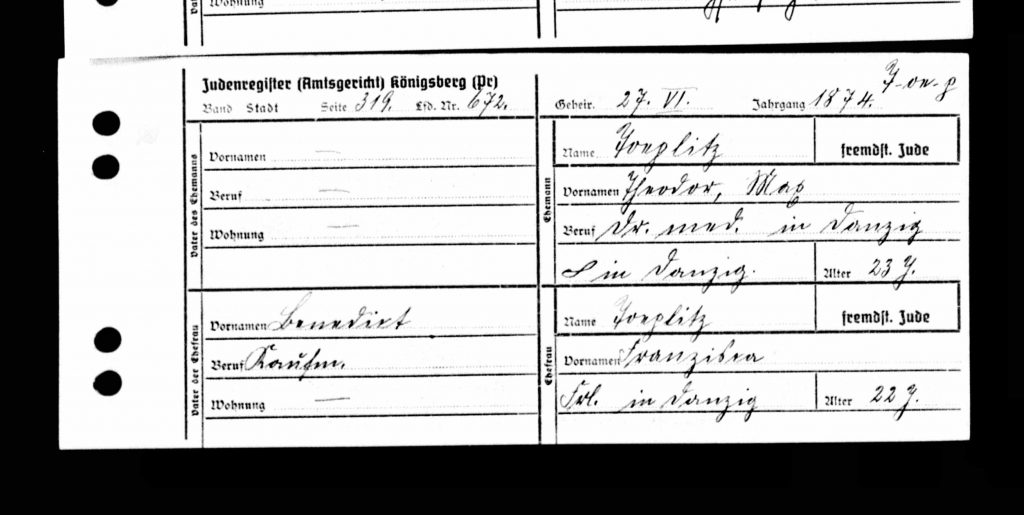

So, Anna Toeplitz was born in Wrocław (Breslau) on April 14, 1879, and was the second of nine children of Dr. Theodor Max and Franziska Toeplitz.

Photographs of Franziska and Theodor Max Toeplitz / Source: Ancestry, Stefan Toeplitz

Marriage certificate of Theodor Max and Francizka Toeplitz, Kaliningrad (Königsberg) / Source: Records of the Evangelical Church in Königsberg

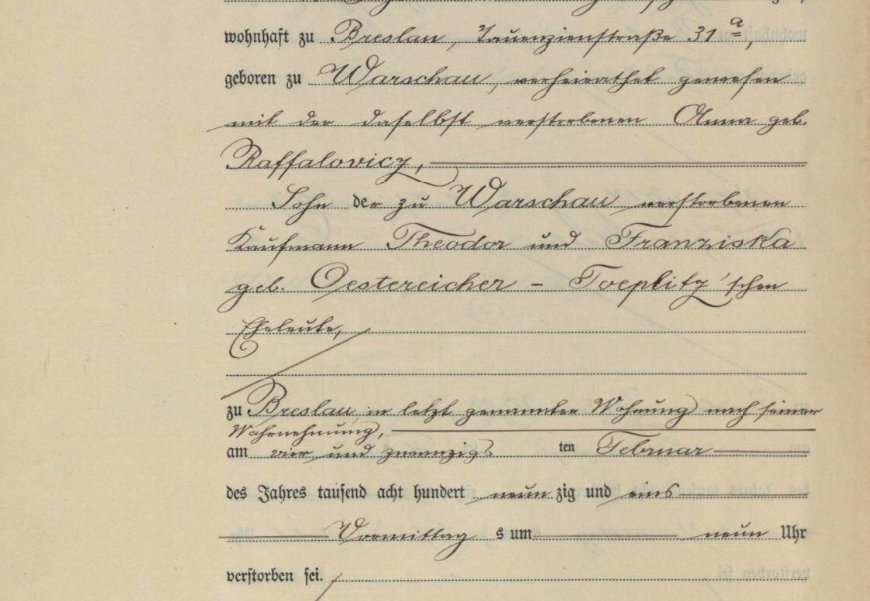

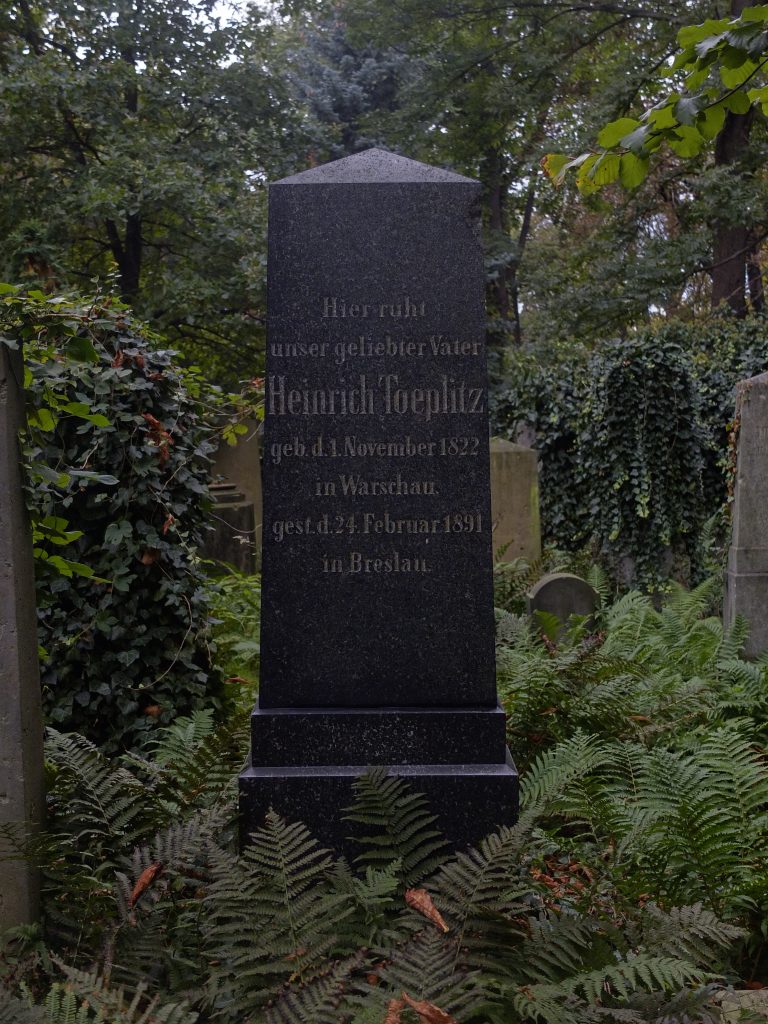

Excerpt from Heinrich Toeplitz’s death certificate / Source: State Archives in Wrocław

Tombstone of Heinrich Toeplitz at the Old Jewish Cemetery in Wrocław / Photo by Marta Maćkowiak

Returning to our heroine – Anna’s husband, Franz Drescher, passed away in Wrocław on January 20, 1934. Two years later, on October 12, 1936, Anna reported her mother’s death. She was living at Nova Strasse 4 (today’s Ksawery Liske Street) at that time.

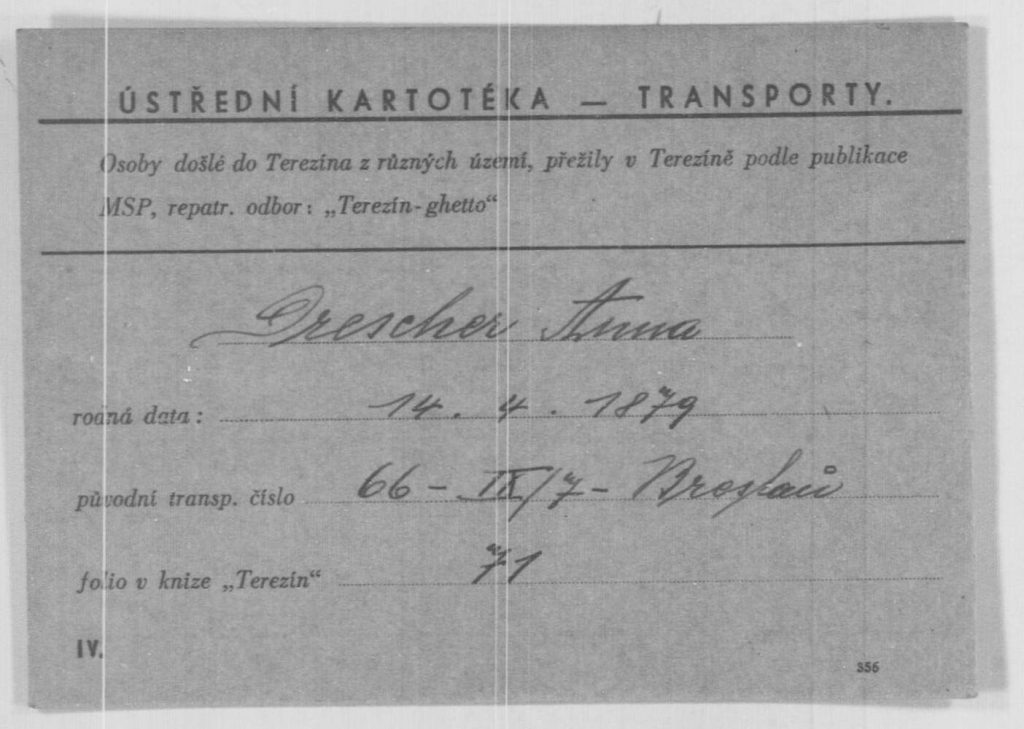

At least since December 1938, Anna was residing in Karpacz. In the following years, Nazi officials must have uncovered her Jewish roots because on January 8, 1944, she was sent to the Theresienstadt camp. Fortunately, the story has a happy ending because in 1946, Anna registered with Sharit haPlatah – the Central Committee of Liberated Jews in Bavaria.

Transport document for Anna Drescher to the Theresienstadt camp (Terezin) / Source: International Tracing Service, Bad Arolsen

Sources:

Villa Felicia. Today, we will delve into a short history of a villa located in Cieplice Śląskie-Zdrój (Bad Warmbrunn). Lately, it’s been haunting me. It all started when I admired its magnificent structure through the window of my temporary apartment, which was located diagonally across the street. A few weeks later, I stumbled upon a photo of the villa in the state archive, wedged between documents from pre-war Wrocław. And when one day I came across a property listing for an apartment in that very building, with information that it used to belong to Dr. Moses, I decided it was time to find out more about this mysterious person.

Advertisement of the villa as a scratchpad among other archival documents / Photo by Marta Maćkowiak

Sigismund Moses was born on August 16, 1863, in Trzebnica (Seebnitz) near Lubin, into a Jewish family, the son of Abraham Moses and Bertha (née Russ). Shortly afterward, the Moses family moved to Jelenia Góra (Hirschberg), while Sigismund eventually settled in Kostomłoty (Kostenblut). It was there that, on March 17, 1889, his first child, a daughter named Katharina, was born. Two months later, Sigismund married Katharina’s mother, Felicia (née Heidenfeld), in Wrocław (Breslau). Felicia was originally from Wrocław, and it is likely that a few years later, they named the Cieplice villa after her. This villa was situated just a few steps away from the spa park.

The Moses family had been residing in Cieplice certainly before 1912, as in that year, on August 6, their daughter Katharina, a resident of Cieplice, married Max Wolff, the bank director from Tarnowskie Góry (Tarnowitz), who was the son of Sigismund and Maria (née Finkler). Max lived in Wrocław, and it was there that the entire family eventually settled. The Wolff family became members of the Nowa Synagoga (New Synagogue), where their son Klaus had his Bar Mitzvah on April 22, 1933.

Information about the upcoming Bar Mitzvah of Klaus Wolff / Breslauer Jewish Community Magazine, Issue 2, February 1933.

Sigismund himself was an extraordinary individual. He was a general practitioner and spa doctor, as well as an author of publications about Jewish sanatorium hospitals (one of them was located in the building at ul. Św. Jadwigi Śląskiej 16 in Cieplice). He was also a member of the Jelenia Góra (Hirschberg) Masonic Lodge, known as the Kynast Loge, whose headquarters were situated on Wilhelmstrasse in Hirschberg (present-day al. Wojska Polskiego 2).

The building that housed the Jelenia Góra Masonic Lodge Kynast Loge zu den Drei Ringen, al. Wojska Polskiego 24, Jelenia Góra / source: Polska-org.pl

The building that served as the headquarters of the Jelenia Góra Masonic Lodge Kynast Loge zu den Drei Ringen, al. Wojska Polskiego 24, Jelenia Góra / photo: Marta Maćkowiak

In 1927, Dr. Moses still resided in Cieplice at Hermsdorferstrasse 5 (today’s Cieplicka Street), precisely where Villa Felicia was located. From around 1930, he permanently moved to Wrocław. At that time, he lived at Furstenstrasse 64 (present-day Grunwaldzka Street), and six years later, he relocated to Hohenzollernstrasse 58 (today’s Sudecka Street).

Excerpt from the 1927 address book of Cieplice Zdrój (Bad Warmbrunn).

Excerpt from the 1936 address book of Wrocław (Breslau).

Photographs of Katharina Wolff, née Moses, and Max Wolff / Source: Yad VaShem

Medical certificate of Max Wolff’s death in the Buchenwald concentration camp

Death certificate of Max Wolff / Source: Stadtarchiv Weimar

On August 19, 1941, Sigismund passed away, resting beside his beloved wife at the new Jewish cemetery in Wrocław, located on Lotnicza Street.

At this moment, Katharina was left entirely alone. Her daughter managed to escape to Palestine, and her son to the United Kingdom. On March 2, 1942, she was forced to leave her apartment on the prestigious first floor and rent a 35-square-meter room in a flat at Gartenstrasse 90 (nowadays Piłsudskiego Street in Wrocław). She lived there for only a year because on March 12, 1943, she was deported to a concentration camp.

A snippet from documents in the file related to the confiscation of Jewish property in Wrocław. Information about Katharina’s children.

A snippet from documents in the file related to the confiscation of Jewish property in Wrocław. Information about the rented room.

Sources:

On September 12th, 1926, Hedwig Krause, a 33-year-old resident of Bad Flinsberg (Świeradów-Zdrój), the wife of a butcher’s master, dies in a car accident on a bend leading from Seidorf (Sosnówka) to Baberhäuser (Borowice).

There are many articles about the stone commemorating the tragic event at Liczyrzepa Street. But there is nothing about Hedwig herself – who was she? Where was she from? It turns out that there is an interesting story behind the monument.

Photo by Marta Maćkowiak

Hedwig Krause from Bad Flinsberg (Świeradów-Zdrój – but was she, really? Hedwig was not born there. She also did not die on the day of the accident, on September 12th, as the inscription on the monument commemorating the event states. It is unknown what happened exactly, whether she was run down or there was a collision between two vehicles, or the driver lost control over the steering wheel – but it is certain that Hedwig did not die on the spot.

She was transported from the place of the accident to the hospital in Hirschberg (Jelenia Góra), where the death was confirmed the next day, September 13th, 1926, at 11:00 p.m.

Hedwig did not come from Bad Flinsberg or Seidorf, or from any other nearby town. She had lived in the vicinity of the Jizera Mountains for at least 6 years because on January 20th, 1920, she got married in Bad Flinsberg. Her husband was the butcher, Wilhelm Gustav Krause, 16 years older than Hedwig.

Hedwig Emilia Minna née Schulze was born on June 2nd, 1893, in a town 200 km away from Flinsberg – in Frankfurt on the Oder. She was the daughter of a butcher’s master, Richard Schultze and Minna née Frikel, who lived even further away, in Küstrin (Kostrzyn nad Odrą). Richard and Minna lived in the Old Town in the house at number 115. However, there is no trace of the house today apart from a few bricks and a piece of the foundation that have survived. But certainly nothing more because the Old Town of Kostrzyn, called by some the Pompeii on the Odra River, was razed to the ground in 1945.

The groom, rather older than younger, as he was 43 on his wedding day, was born on December 11th, 1877, in Bad Flinsberg. He lived in house number 149, probably on Hauptstrasse (today ul. 11 Listopada), according to the information from the address book dated as 1930, Gustav was the son of the glazier Erdmann Krause, who started renting guest rooms at the end of his life in his house in Schreiberhau (Szklarska Poręba), and Augusta née Männich.

A piece of address book from Bad Flinsberg, 1930

A death record of Hedwig Krause née Schulze

Wilhelm Gustav Krause had at least three siblings, two older brothers, Julius Erdmann and Gustav Oskar and a sister, Anna.

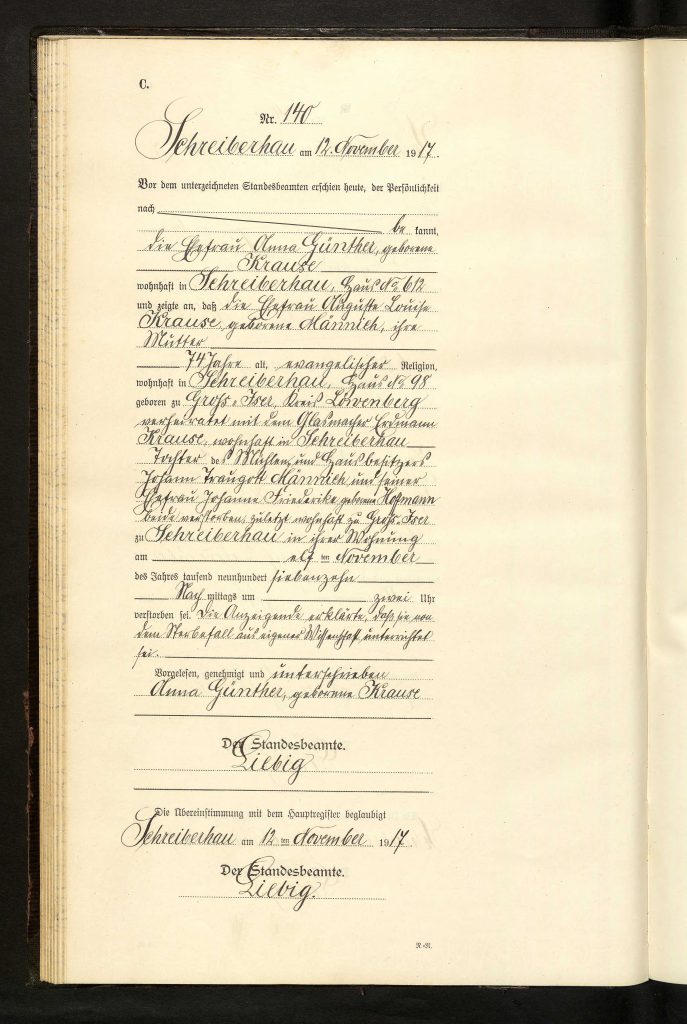

On November 12th, 1917, Anna Krause née Günter, reports to the Registry Office that her mother, Auguste Louise Krause née Männich died the day before at 11:00 a.m. in her house at number 98 in Schreiberhau. She also added that Auguste was 74 years old and was born in Gross Iser as the daughter of Johann Traugott Männich and Johanne Friederike née Hoffmann. The daughter of Johann, the owner of the mill and a house in Gross Iser. And as it turned out later – the founder of the now non-existent Isermühle shelter in the former settlement of Gross Iser.

In 1874, Auguste, Erdmann and their newborn son Julius stayed with their grandparents in this small village in the Jizera Meadow. Later, however, they will move first to Bad Flinsberg and finally to Schreiberhau.

Hostel Isermühle / Source: Polska-org.pl

The Isermuhle’s remains / Source: Ragnar, Polska-org.pl

On July 15th, 1921, Julius Erdmann Krause, a forester living at Erlenweg 828 (today’s Zdrojowa Street) in Szklarska Poręba Górna, reported the death of his 80-year-old father, also Erdmann. He rested next to his wife, Auguste, in the Evangelical cemetery in Szklarska Poręba.

Going back to Gustav and Hedwig – it is unknown whether they had any offspring within 6 years of living together. It is also not known what happened to Gustav after the tragic death of his wife.

However, I came across an interesting information – namely the remark about Wilhelm Gustav Krause from Bad Flinsberg, the father of three children, who died on November 29th, 1939, in Cieplice Zdrój, the husband of Dorothea Schulze, born on March 24th, 1907, in Küstrin.

The question is – is it a coincidence or Hedwig’s younger sister?

The Protestant cemetery in Schreiberhau (Szklarska Poręba) / Photo by Marta Maćkowiak

Sources:

Today, another story, the starting point of which was a trace of a mezuzah found by Janka from Krakuska City Guide and secured by Aleksander from Mi Polin in a tenement house at ul. Sebastiana 19 in Krakow. Let’s see who lived there once.

Photos by Aleksander Prugar

One of the families living in a Kraków tenement house at ul. Sebastiana 19 was the

Wachtel family – Henryk, Helena and their daughter Maria.

Henryk and Helena, in fact, Chaim Wachtel and Chaja Baustein, got married on June 30th, 1908, in Jarosław, where the groom held the position of a private clerk. It is not known how

they both ended up in a city several hundred kilometres away from their homeland, but they spent several years there.

Henryk was born in Słotwina on August 11th, 1881 as the son of Izak Wachtel and Rywka née Gleitsman, while Helena came from Podgórze, where she was born on April 1st, 1885 as the daughter of the merchant Joshua Baustein and Malka Schudmak.

A piece of Chaim Henryk Wachtel and Chaja Helena Baustein’s marriage record / Source: State Archive in Przemyśl

One and a half year after their wedding day, their first child, the daughter Maria, was born

in house number 161 on September 12th, 1909. After the next 4 years and moving into the new house at number 52, their son Osias was born on August 19th, 1913. Osias changed his

name two times – first to Oskar, and finally to Aleksander.

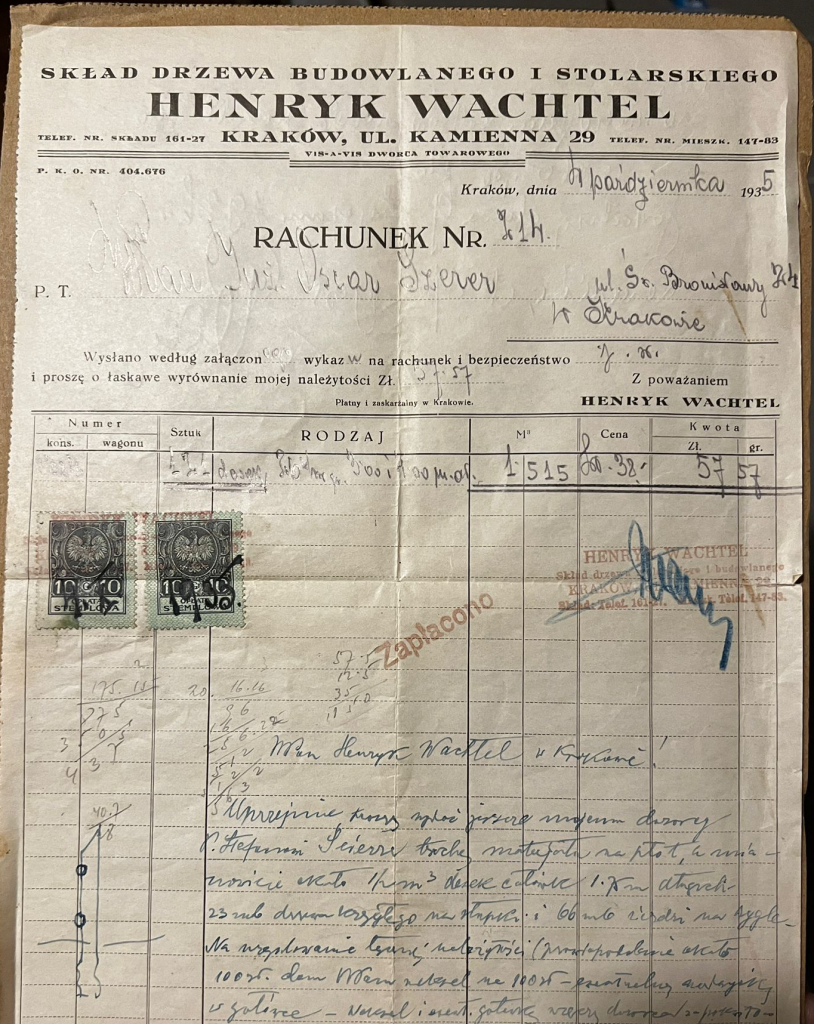

In the meantime, Henryk worked as a clerk in Jarosław and Krosno. After 1914, the family settled permanently in Kraków, and Henryk started a timber business – he began running a construction and carpentry timber yard based at ul. Kamienna 22 (I found a bill from

1935 at the Internet auction!)

Henryk Wachtel’s construction and carpentry timber yard’s bill / Source: Aleksander Prugar

The address book from 1936

Henryk and Helena survived the war – the notes in the marriage certificate evidence this, according to them, in the 1950s, they officially changed their names and surnames: from

Chaim to Henryk, from Chaja to Helena, from Wachtel to Wachniewicz. After the war, they lived in Warsaw, where their son Aleksander started a new life. He buried his mother in 1964 in the Jewish cemetery on Okopowa Street. The fate of Maria, the daughter of Henryk and Helena, Alexander’s sister, remains unknown.

A photography of Maria Wachtel / Source: Jewish Historical Institute in Warsaw

A protocol concerning Jewish inhabitants of Kraków – in the picture: Henryk Wachtel, 1940 / Source: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

A grave of Helena Wachtel buried at Jewish cemetery in Warsaw on Okopowa Street / Source: Foundation for Documentation of Jewish Cemetries in Poland

Sources:

The Civil Registry Office (Urząd Stanu Cywilnego) is the first important institution to start genealogical research. Knowledge about our ancestors often ends with grandparents, or in the best case, great-grandparents. Frequently, only the names are known, and the exact date and place of birth seem impossible to determine. Many claim that there is no chance of discovering information about further generations because “grandma burned the documents in anger,” “there is no one left to ask,” or “grandpa refuses to talk about what happened.”

The good news is that even in such situations, not all is lost, and assistance can come from the Civil Registry Office.

At the Polish Civil Registry Office, you’ll find birth records less than 100 years old, as well as marriage and death records less than 80 years old.

After this time, theoretically, the documents are transferred to the State Archive (Archiwum Państwowe). They can then be freely accessed for viewing in the archive’s reading room or remotely, if they have been scanned and made available in an online search engine.

In theory – because there are sometimes delays in transferring the records, it can also happen that several years are grouped together in one register. In such cases, one may need to wait until the most recent year reaches the 100-year mark.

The documents held in the Civil Registry Office are protected under personal data regulations, so not everyone has access to them.

This means that you can easily request a copy of your grandmother’s birth certificate. However, if you need the birth certificate of her sister or brother, you’ll have to ask for assistance from your uncle, aunt, or cousins.

If the person whose document you’re interested in was born in a larger city, their birth certificate will be kept in the local Civil Registry Office. The same applies to marriage or death certificates.

In the case of a smaller town or village, start by determining the municipality to which the place belongs. If you’re unsure, it’s worth calling the nearby Civil Registry Offices and asking the clerk. Sometimes they can quickly check if a particular record exists. Occasionally, it may turn out that documents from a specific year have been destroyed, or depending on the period, they may be stored in several different Civil Registry Offices – so it’s worth inquiring.

You can obtain a copy of a document in three ways:

The abbreviated copy costs 22 złoty, while the complete copy costs 33 złoty. It’s worth paying the extra 11 złoty because the complete copy includes all the information from the original document, including annotations that can be vital for genealogical research, such as details about adoption, name changes, religious conversions, deaths, and marriages.

The response from the Civil Registry Office can be either positive or negative. In the case of a positive response, you will receive a copy of the document containing new information about your ancestors. However, it may also happen that the document is not found. There could be several reasons for this:

In the meantime, I’ll be rooting for successful applications!

Talk to you later,

Marta

The cemetery gate in Stara Kamienica clearly indicates that it was functioning here before the Second World War. At first glance, it can be said that all graves are modern. If you walk the main alley to the very end, you will pass a tiny chapel and reach the left corner. There you will find a storage site of pre-war tombstones – most in parts, some completely unreadable and some in quite good condition. One of them belonged to Gustav Köhler, the railway station manager.

Photos by Marta Maćkowiak

Gustav died in his home in Stara Kamienica (German: Alt Kemnitz) on February 22nd, 1904, at the age of 78. According to his son, the merchant Willy Köhler, it happened at 8:15 p.m. He was survived by his wife, Augusta Ernestine née Seibt and children. Gustav’s father and grandfather were not the residents of Stara Kamienica – he came to this area from Nowa Rola (German: Niewerle) located 140 km away, where he was born on June 17th, 1825, as the son of Gustav Eduard Kohler and Johanna Christina née Zeimke. At least that’s the information provided to the civil registrar who recorded the death – according to the baptism certificate, Gustav was the illegitimate child of Johanna Christina Zeimke. Perhaps his parents got married after his birth, he was adopted by Gustav Sr., or perhaps he passed on such a story to his wife and children.

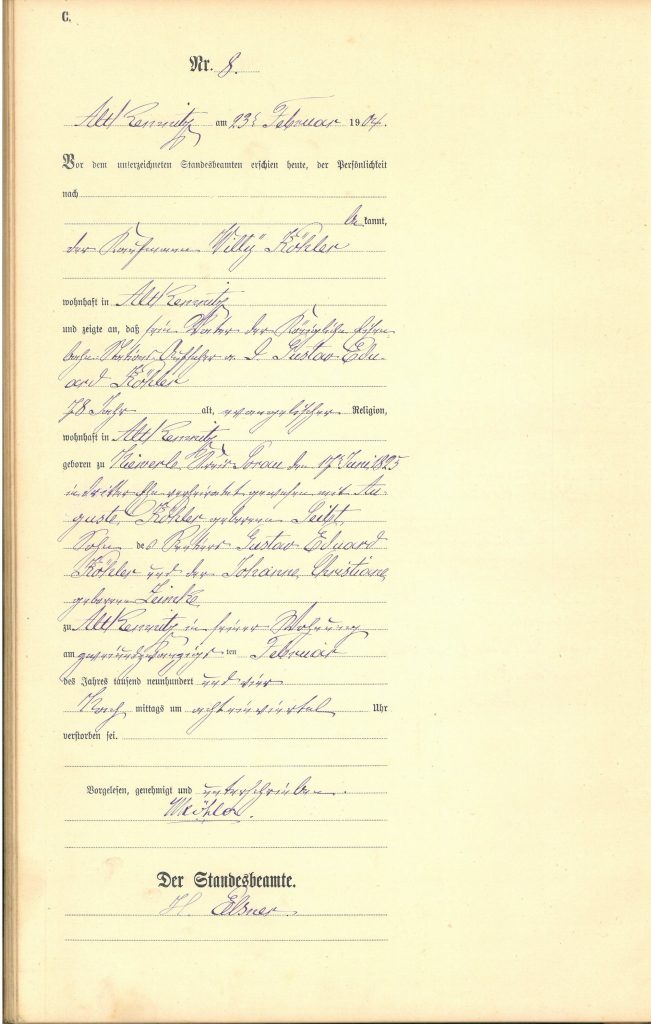

The death record of Gustav Kohler / Source: The State Archive in Wrocław, Jelenia Góra branch

16 years after Gustav’s death, on March 26th, 1920, at 11:00 a.m., his wife Augusta Ernestine also passed away at the age of 81. Her death was reported by her second son, Kurt Köhler. Augusta was born nearby, in Kopaniec (German: Seifershau), less than 6 km away. She was the daughter of Friedrich Seibt and Beate née Schroeter.

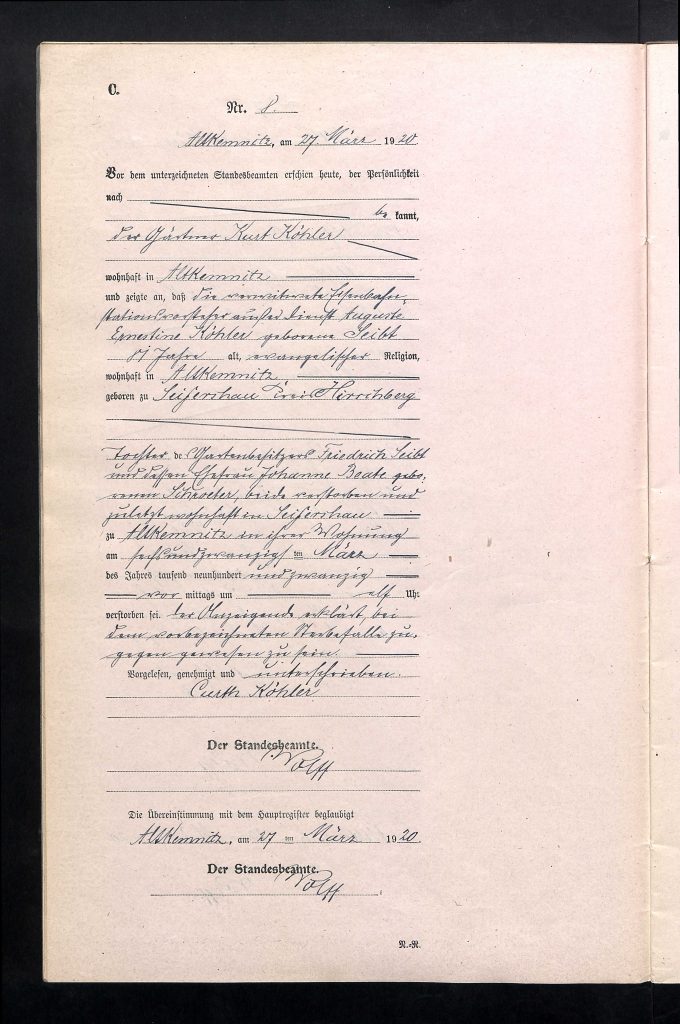

The death record of Augusta Ernestine Köhler / Source: The State Archive in Wrocław, Jelenia Góra branch

In accordance with the list of residents of Alt Kemnitz dated 1930, Kurt Köhler lived in the house at number 62 – comparing the maps, it seems that the numbering remained practically unchanged, and the Köhler house was located at today’s Kasztelańska Street – 95 m from the station.

The question is – what happened to the sons of Gustav and Augusta – Kurt and Willie?

Building No. 62 in Stara Kamienica – then and now

Railway station in Stara Kamienica then and now / Source: polska-org.pl, photo: RobTur

Sources:

Between Kwieciszowice (German: Blumendorf) and Proszowa (German: Kunzendorf Gräflich), two villages in the Izera Mountains, there is a small, forgotten cemetery. It is easy to overlook it when you do not know about it, but the enthusiasts of cemetery trips will certainly notice a suspicious little grove in the middle of the field.

Photos by Marta Maćkowiak

Tall, evenly planted trees still indicate the main avenue leading to several collapsed crypts and a ruined shrine.

On the right and left, you can see a lot of nameless tombstones, broken pieces of plates and a few ones on which it is possible to read something. One of them is Ida Fischer’s plate, whose story I decided to explore.

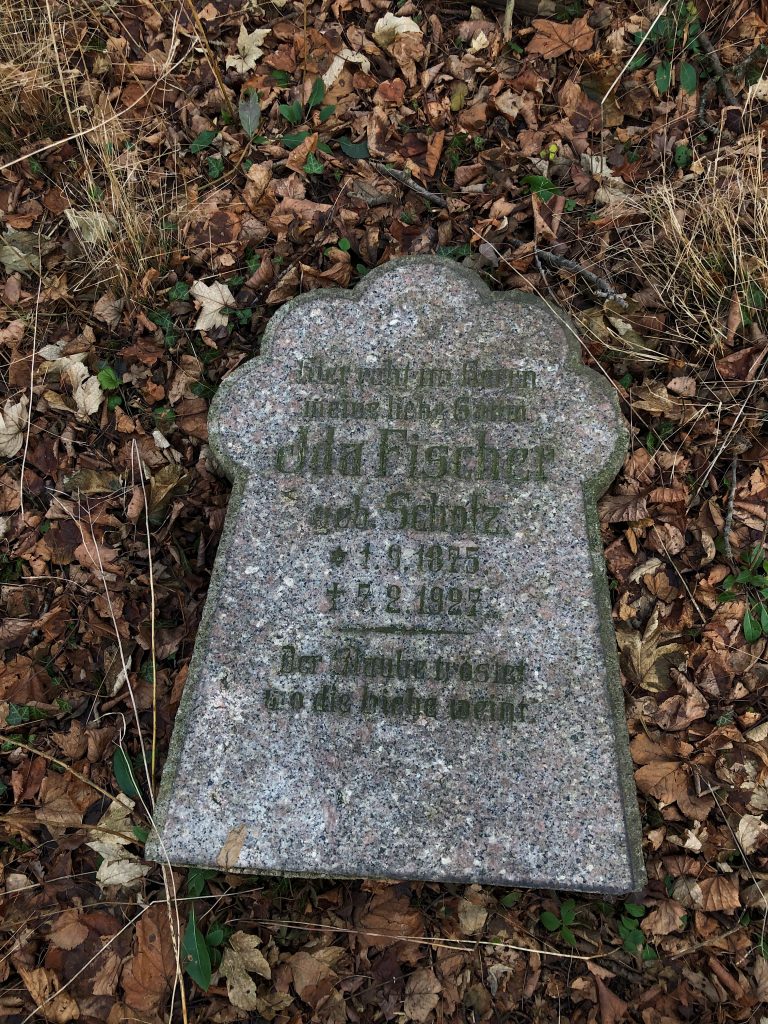

Gravestone of Ida Fischer née Scholz / Photo by Marta Maćkowiak

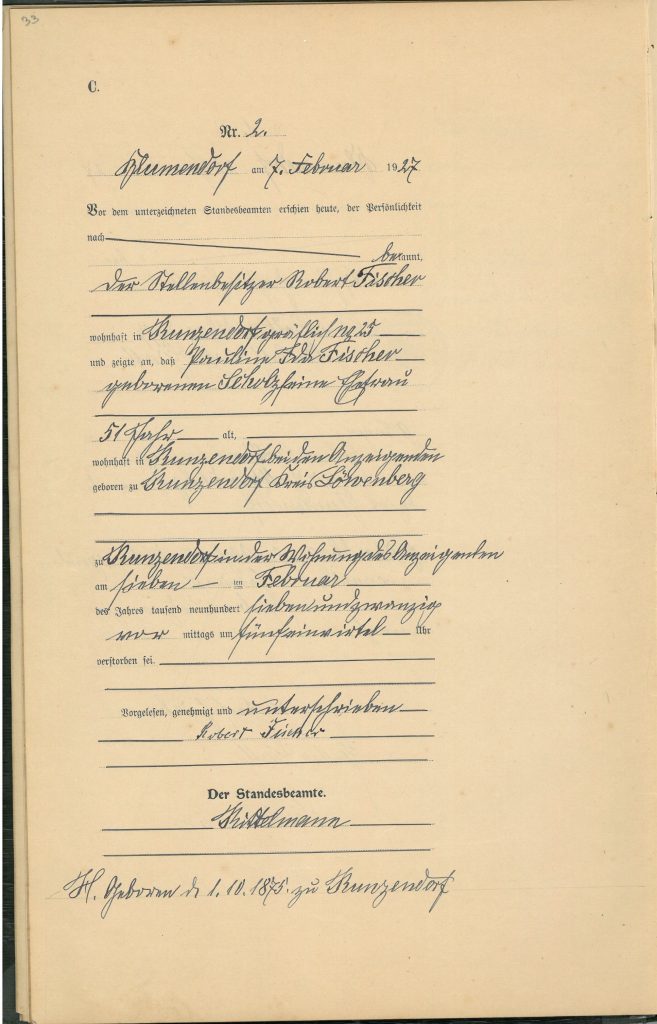

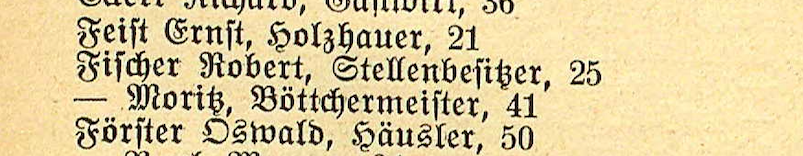

According to the tombstone inscription, Ida Fischer née Scholz, was born on September 1st, 1875, and died on February 7th, 1927, at 51. According to the death certificate I managed to find, Paulina Ida died in her house at Proszowa 25.

Her husband, Robert Fischer, reported the death, who, as it turns out later, will outlive the whole family.

The death certificate of Paulina Ida Fischer nee Scholz / Source: The State Archive in Wrocław, Jelenia Góra branch

Robert and Ida were married for 27 years. They got married on December 10th, 1900, in Kwieciszowice.

Robert was born in Rębiszów (German: Rabishau) on January 20th, 1867. He was the son of the merchant Ferdinand Wilhelm Fischer and Christina Ernestine née Glaubitz.

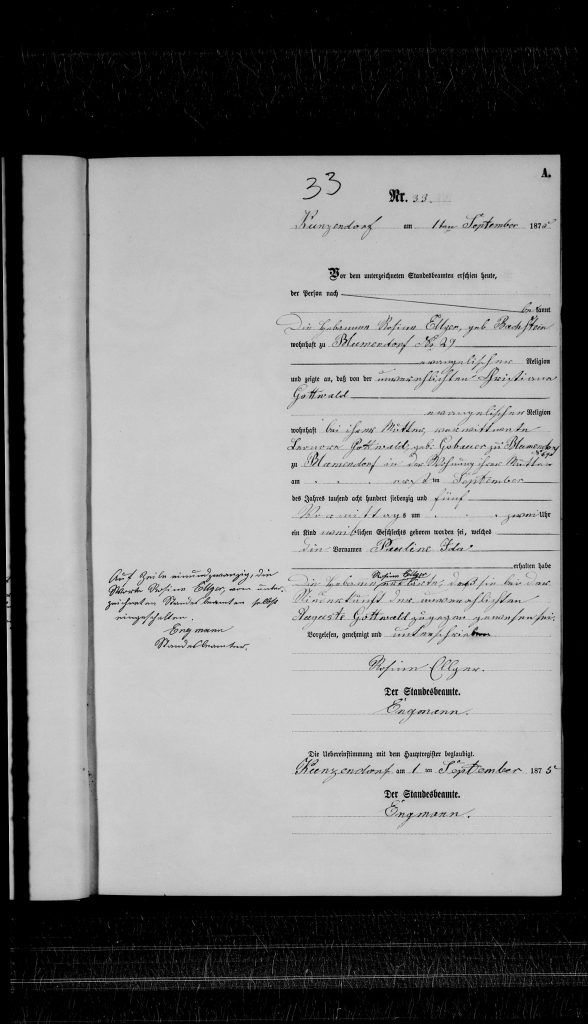

Paulina Ida was born on September 1st, 1875 at 2 a.m. in a house at number 64 in Kwieciszowice (German: Blumendorf) as the illegitimate daughter of Christina Gottwald, who lived with her mother, Leonora Gottwald née Gebauer.

4 years later, on July 22nd, 1879, Ida’s mother, Christina Augusta Gottwald, the daughter of a master blacksmith Karl Gottwald and Johanna née Gebauer, married Ernst Gustav Scholz the son of Ernst Gustav and Gusta née Menzel, in the Evangelical church in Proszowa. During the wedding, the groom admitted to be Paulina Ida’s father.

In 1903, Ida’s mother died, while her father died in 1917 – we can learn from their death certificates that they lived in Proszowa at number 53.

The history written in stone could at least become the history of people who once lived in this beautiful place – Ida, her ancestors and her husband, Robert, who lived and worked for a while because his name appears in the address book from 1935/1936.

The marriage record of Robert Fischer and Paulina Ida Scholz / Source: The State Archive in Wrocław, Jelenia Góra branch

Old Protestant church in Proszowa (Kunzendorf Gräflich) / Source: www.polska-org.pl

The birth certificate of Paulina Ida Scholz / Source: The State Archive in Wrocław, Jelenia Góra branch

Sources:

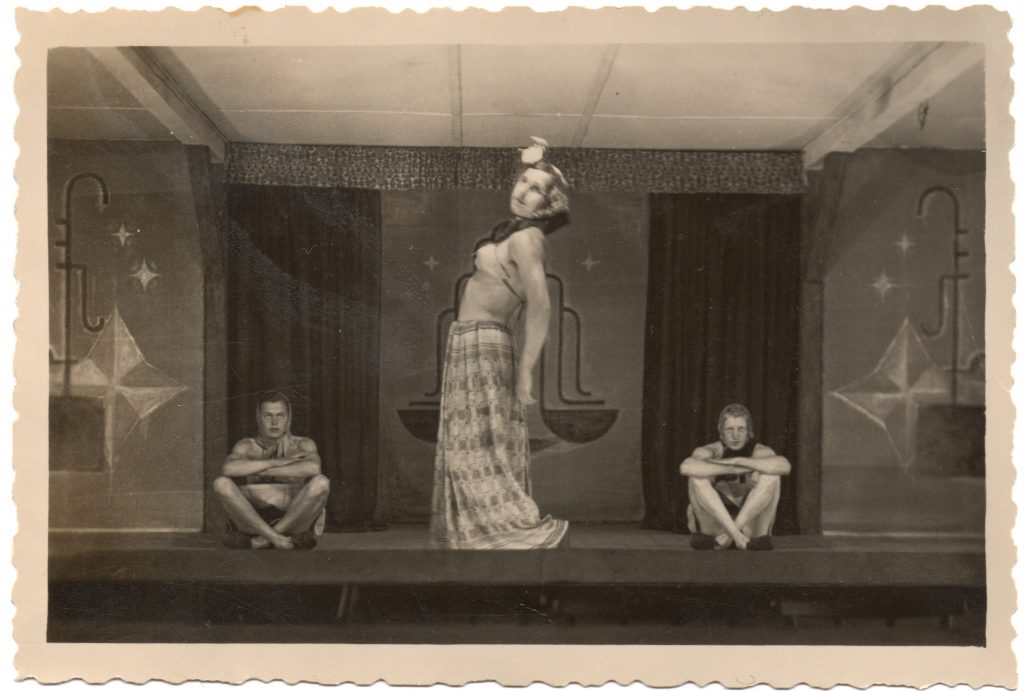

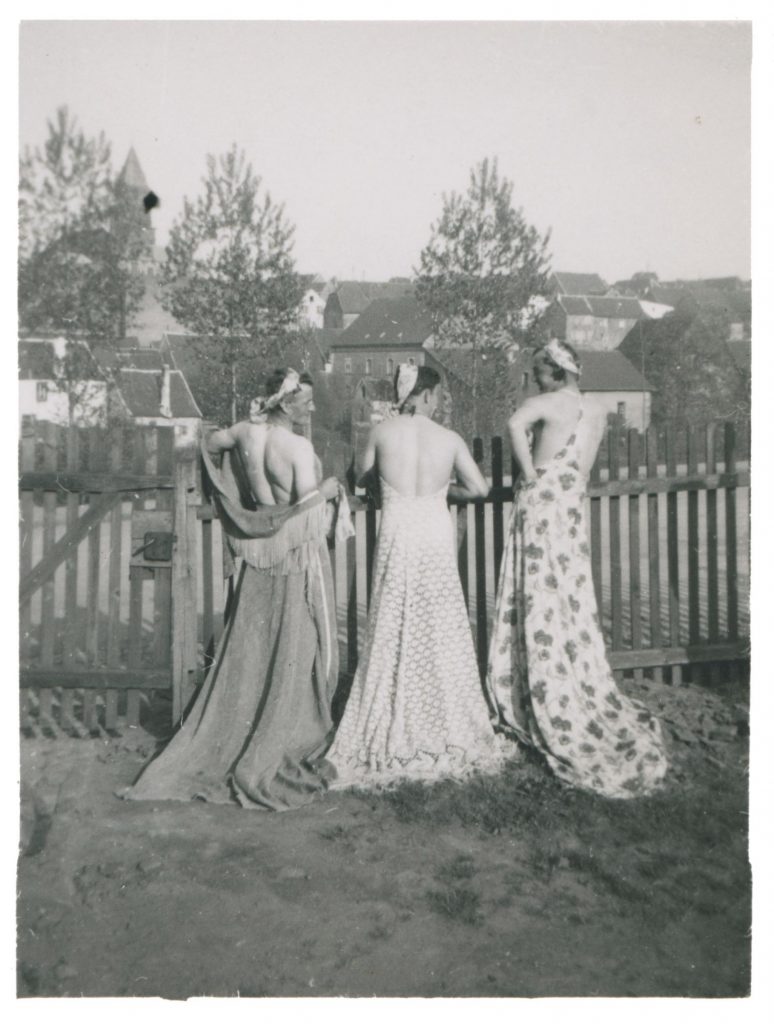

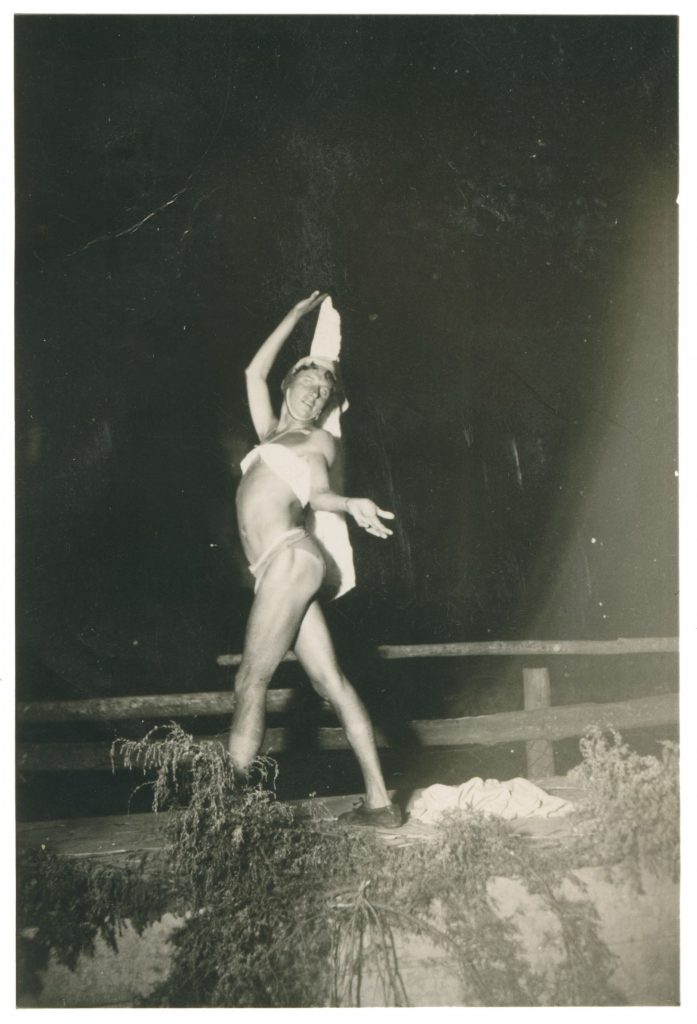

Today I found a gem at the flea market – photos of German soldiers dressed as women. Browsing through boxes with old pictures and postcards, I came across a collection of photos of young men serving in the army. Most of them didn’t stand out in any way, except for two that caught my eye.

Source: private collection

At the beginning I decided to buy 2 portraits of women and 2 short correspondences from the end of the 19th century. I didn’t really want photos of German soldiers in my collection, especially without any additional information that would help me identify someone in the next step.

However, as soon as I left the stall, something told me that it would be worth reconsidering this decision – and as I kept thinking about these pictures, I came back and bought them.

While looking for information that would help me understand the context of these unique items, I came across an article about Martin Damman. An artist who has been collecting photos of German soldiers practicing cross-dressing for two decades. It seems that men in “my” pictures were part of something bigger, as Martin released his book Soldier Studies. Cross-dressing in Wehrmacht containing his photo collection in 2018.

Source: private collection

Dammann, besides presenting his photo collection, reflects on the role that cross-dressing could have played among German soldiers.

On the one hand, he said that it may have referred to German carnival traditions and to theatrical performances with intention to bring relief and entertainment in brutal circumstances. On the other hand, he noted that homosexuality and transgenderism were present among German soldiers, even when faced with the penalty of placement in a concentration camp and death.

Perhaps for some it was an entertainment and emotion regulation, for others it could have been a substitute for normality and the possibility of self-expression.

A short interview with Martin Damman can be viewed here here.

Source: private collection

Source: private collection

Source: private collection

Source: private collection

Source: private collection

Source: private collection

Source: private collection

Source:

Końcowy raport składa się z kopi odnalezionych dokumentów, tłumaczeń, zdjęć oraz podsumowania. Wyjaśniam pokrewieństwo odnalezionych osób, opisuję sprawdzone źródła i kontekst historyczny. Najczęściej poszukiwania dzielone są na parę etapów i opisuję możliwości kontynuacji.

Czasem konkretny dokument może zostać nie odnaleziony z różnych przyczyn – migracji do innych wiosek/miast w dalszych pokoleniach, ochrzczenia w innej parafii, lukach w księgach, zniszczeń dokumentów w pożarach lub w czasie wojen. Cena końcowa w takiej sytuacji nie ulega zmienia, ponieważ wysiłek włożony w poszukiwania jest taki sam bez względu na rezultat.

Raporty mogą się od siebie mniej lub bardziej różnić w zależności od miejsca, z którego rodzina pochodziła (np. dokumenty z zaboru pruskiego, austriackiego i rosyjskiego różnią się od siebie formą i treścią).

Na podstawie zebranych informacji (Twoich i moich) przygotuję plan i wycenę – jeśli ją zaakceptujesz, po otrzymaniu zaliczki rozpoczynam pracę i informuję o przewidywanym czasie ukończenia usługi. Standardowe poszukiwania trwają około 1 miesiąca, a o wszelkich zmianach będę informować Cię na bieżąco.

Na Twoje zapytanie odpiszę w ciągu 3 dni roboczych i jest to etap bezpłatny. Być może zadam parę dodatkowych pytań, dopytam o cele albo od razu przedstawię propozycję kolejnych kroków.

Warto pamiętać, że im więcej szczegółów podasz, tym więcej rzeczy mogę odkryć.

Podziel się ze mną:

I najważniejsze – jeśli masz niewiele informacji, zupełnie się tym nie martw, w takich sytuacjach także znajdę rozwiązanie.